The Aztec count of days (tonalpohualli in the Nahuatl language) is commonly called the “Aztec Calendar,” a ritual cycle of 260 days in 20 13-day “weeks” or trecenas, its purpose divinatory or prophetic. Like the well-known zodiacal system of horoscopes in which a person is born in one of 12 “houses” with character and fate influenced thereby, the Aztec day on which one is born is that person’s ceremonial name and is believed to determine their character and fate. (You can discover your own Aztec day-name by entering your birth-date at www.azteccalendar.com.)

Calling the Tonalpohualli “Aztec” is in fact a historical misnomer. They inherited the basic ritual of the calendar from the ancient Maya, who in their turn adopted it from the even earlier Olmec. I have found circumstantial evidence that the roots of this Mesoamerican ceremonial calendar may reach still deeper into the past, possibly originating in distant South America. See my blog posting on this iconoclastic theory: Source of Aztec Calendar.

The way my obsession with the Tonalpohualli came about is a long and probably tedious story, but I’m going to tell it—if only as a cautionary tale about unbridled enthusiasm. Over several decades, my possession by the Aztec muse happened gradually, simple curiosity growing into bemused fascination, to an eccentric fixation, and then to a full-fledged obsession.

Like most folks, in high school I learned about the conquest of the heathen Aztecs by the devout Catholic Conquistador Hernando Cortez in 1519, supposedly thanks merely to his miraculous horses and muskets. (Only in the 90s did I learn that his dramatic victory was actually thanks to10,000 Tlaxcalan warrior allies, and that the godly Conquest destroyed a monumental city, an efflorescent culture on a par with the Roman empire, and untold millions of native peoples.)

In the later 70s I came across a later16th-century narrative by Fray Diego Duran about the arduous legendary migration of the barbarian Aztecs into the Valley of Mexico and was intrigued by the intertwined story of their war-god Huitzilopochtli, Hummingbird of the South. For a while I sketched out a pseudo-sci-fi novel about that journey but finally abandoned the project.

About ten years later, a friend passed me the book “The King Danced in the Marketplace” by Frances Gilmore which gave me somewhat more information on the Conquest, though hardly less fanciful or slanted. In the story of the Aztec ruler Montezuma, the author also made an off-hand comment that the Aztec “century” was only 52 years long, counted in four sequences of thirteen. Being a crypto-mathematician, I was struck by the numerical system—and by the curious fact that it sounded exactly like a deck of playing cards.

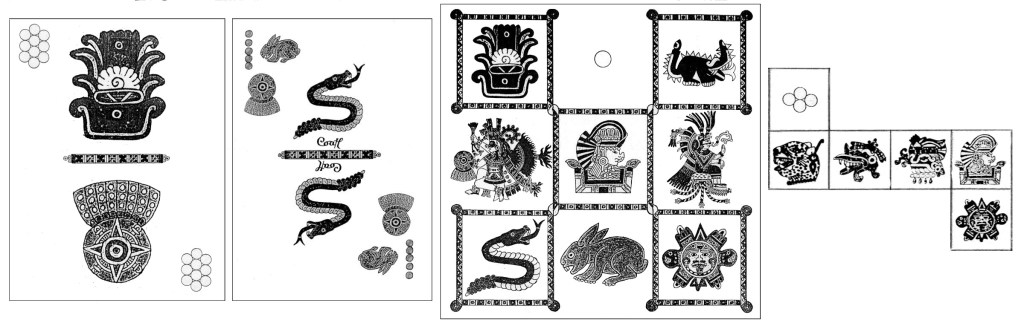

That inspiration triggered a creative frenzy in the later 80s. On the model of the century-count, I laid out a deck of cards with eight intersecting suits called Palli for the four 13-year periods. Then, discovering that the ceremonial year was counted in 20 sequences of 13 numbered days, I created another deck called Tonalli (days) to reflect that cycle. Having nowhere to go with these “inventions,” I forged on to design a Tarot-type fortune-telling deck called Ticitl (priest/teacher), a couple unworkable board games, and a set of six-sided dice. I wrote out detailed rules, but frankly, these thirty years later, I can’t remember how the games were supposed to be played.

Palli Tonalli Ticitl Aztec Dice

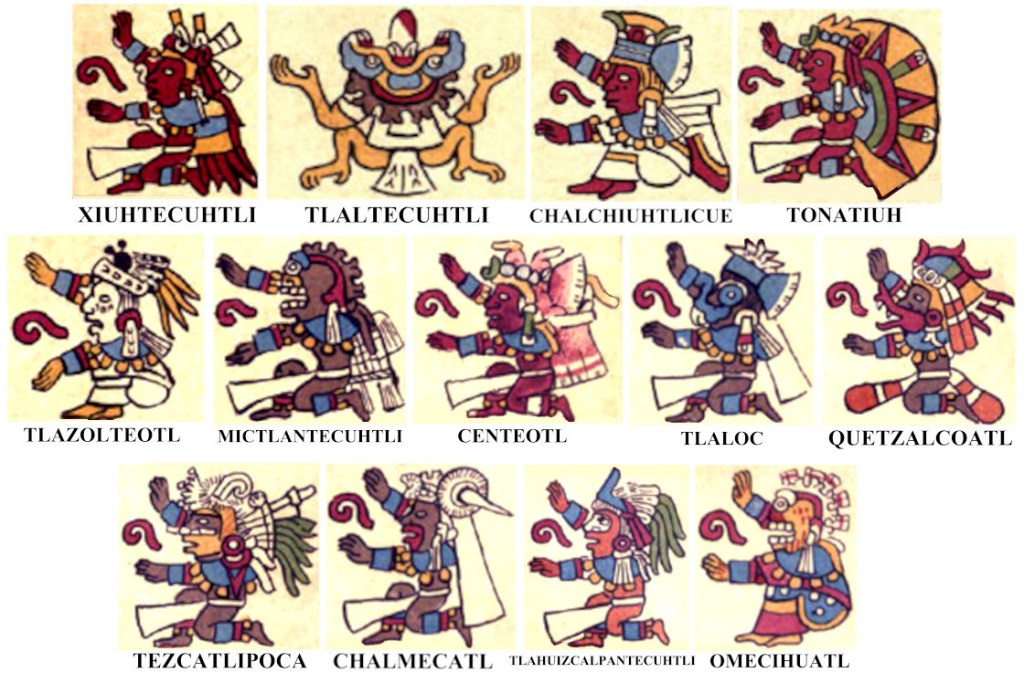

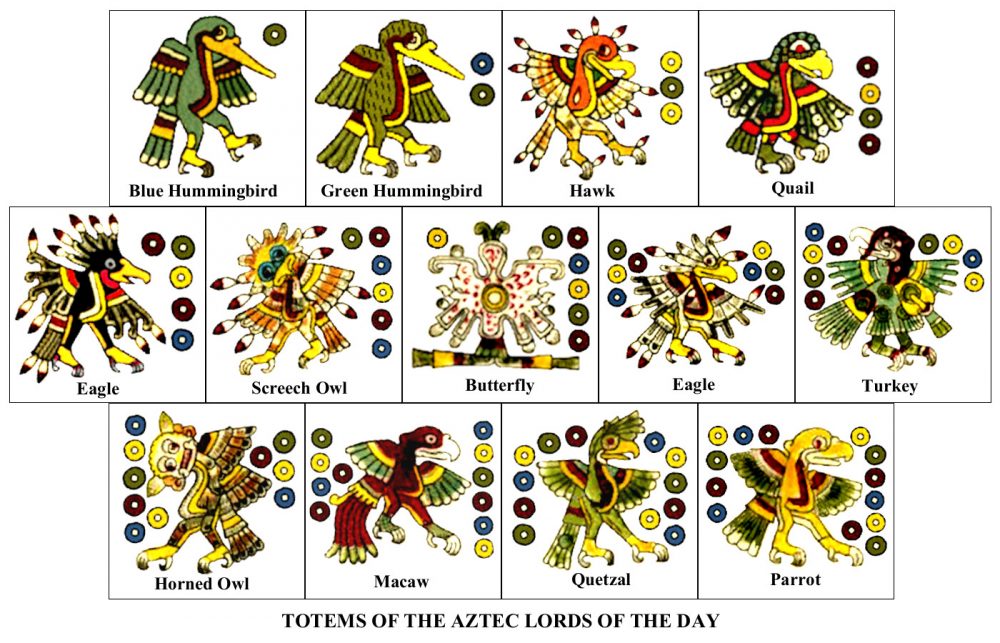

Only much later did I come to understand the complicated connection between the 52-year century, the 260-day Tonalpohualli, and the solar year with 18 months of 20 named days. However, in the course of working on those games, I’d drawn all the day signs and several deities, mostly on popular models from the Codex Borbonicus, and when I decided in the early 90s to create my own Aztec Book of Days (published in 1993), all I had to do was lay out the trecenas and draw the other patron deities. Coloring them was time-consuming but great fun.

In those BI (Before Internet) years, finding authentic models for those other Aztec deities was almost impossible. Fortunately, in the University of New Mexico library I found a rare facsimile of the Codex Nuttall, which I photographed and studied for figures, regalia, and paraphernalia. (More than a decade later I happened upon “The Codex Nuttall” in a 1975 Dover edition.)

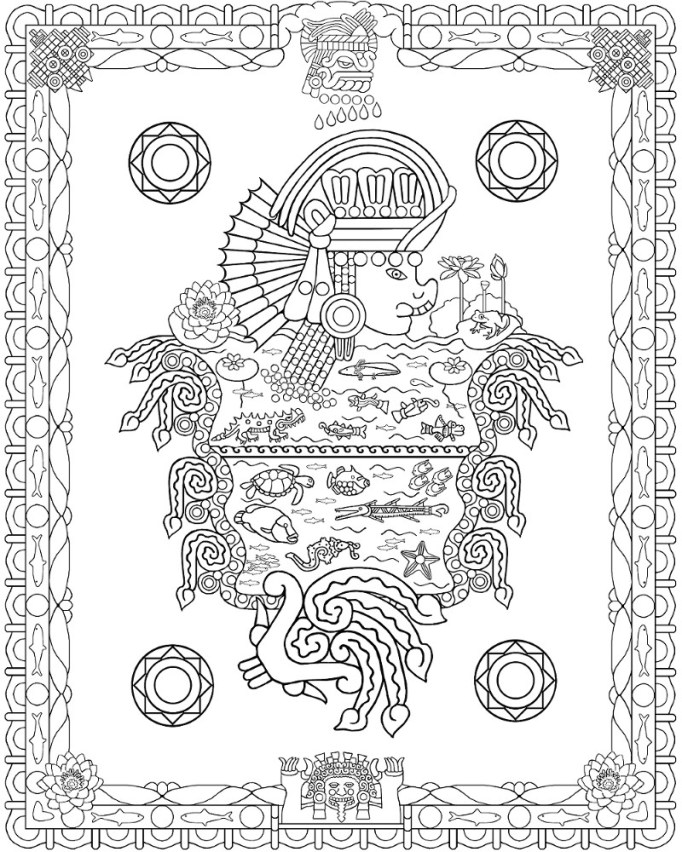

I had no way of knowing at the time that Nuttall was actually a historical document rather than a ritual model. As a result, my images of the deities largely reflected that secular iconography. However, my skewed artistic inspiration produced 20 trecenas with eye-catching deities which are often viewed on my website www.richardbalthazar.com under “Aztec Images.” (Visitors have often used them with my compliments for design purposes on clothing, other products, and even tattoos.) One of my more imaginative Nuttall-inspired creations was the God of the Moon:

Resting on these Aztec artistic laurels, for the next dozen years or so I turned to sculpture (found-object assemblages). Though focusing on sculpture, I still had the Aztec bug, and amongst many abstract works, I created figures of various Aztec-deities and day-signs. By 2008. my enthusiasm for sculpture faded, and I reverted to my old Aztec obsession, creating another deck of cards. “Six Snake” was much simpler than my earlier calendrical fantasies, composed of 54 cards with six suits of nine in the colors of the rainbow. Intended as a game for children to learn math, it worked on the closed numerological system of collapsing numbers to a single digit, 1 to 9. But the elegant idea proved to be flawed because it could only handle addition and multiplication; subtraction and division were beyond its scope.

After that, in the later AI (After Internet) years, I assembled a complete collection of the other Aztec codices that survived the book-burnings after the Conquest of Mexico and wrote a summary treatise on them: Ye Gods! The Aztec Codices. Studying these hundreds of ancient pages, I identified the vast Aztec assortment of gods and goddesses and posted an illustrated encyclopedia of them on my website: Ye Gods! The Aztec Pantheon.

Over the next several years I used these authentic images to create digital black-and-white icons of 20 deities for a coloring book called Ye Gods! The Aztec Icons.

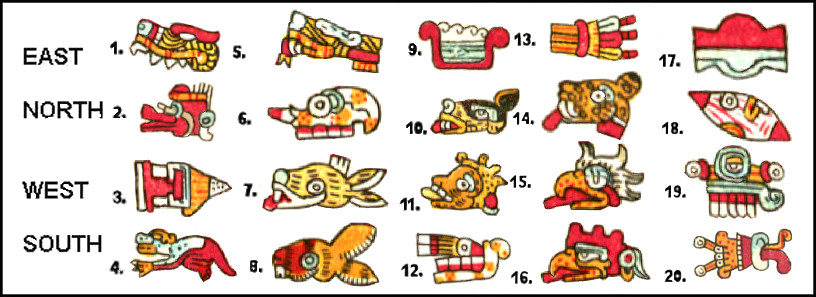

In the midst of these painstaking digital drawings, in 2018 I was once again seized by the mania for cards and made a deck reflecting both the Tonalpohualli and the Aztec concept of specific gods and groups of days representing the cardinal directions. Those cards turned out to be too complicated to play with reasonably, but I presented them in a blog entitled “Aztec Gods of the Directions,” which for some odd reason has become far and away the most popular of my posts.

Early in that same year, I had my icons printed on large-scale vinyl banners for an informational exhibition called Ye Gods! Icons of Aztec Deities. The exhibition was shown for two years in six venues before tragically being closed down by the covid pandemic in March 2020.

After eight years of drawing icons, this year I turned to re-creating the book of days (tonalamatl) pages from the Codex Borgia for Canadian friend Marguerite Paquin’s use in her blog on current Mayan trecenas, that calendar of course being quite the same as the Aztec. Only last year did I see the faithful full-color restoration/facsimile of the entire Codex Borgia published in 1993 by Gisele Díaz & Alan Rodgers (Dover Publications), but my digital re-creations are much freer in color and “rectified” detail, creating images essentially impossible for the ancient Aztec artists.

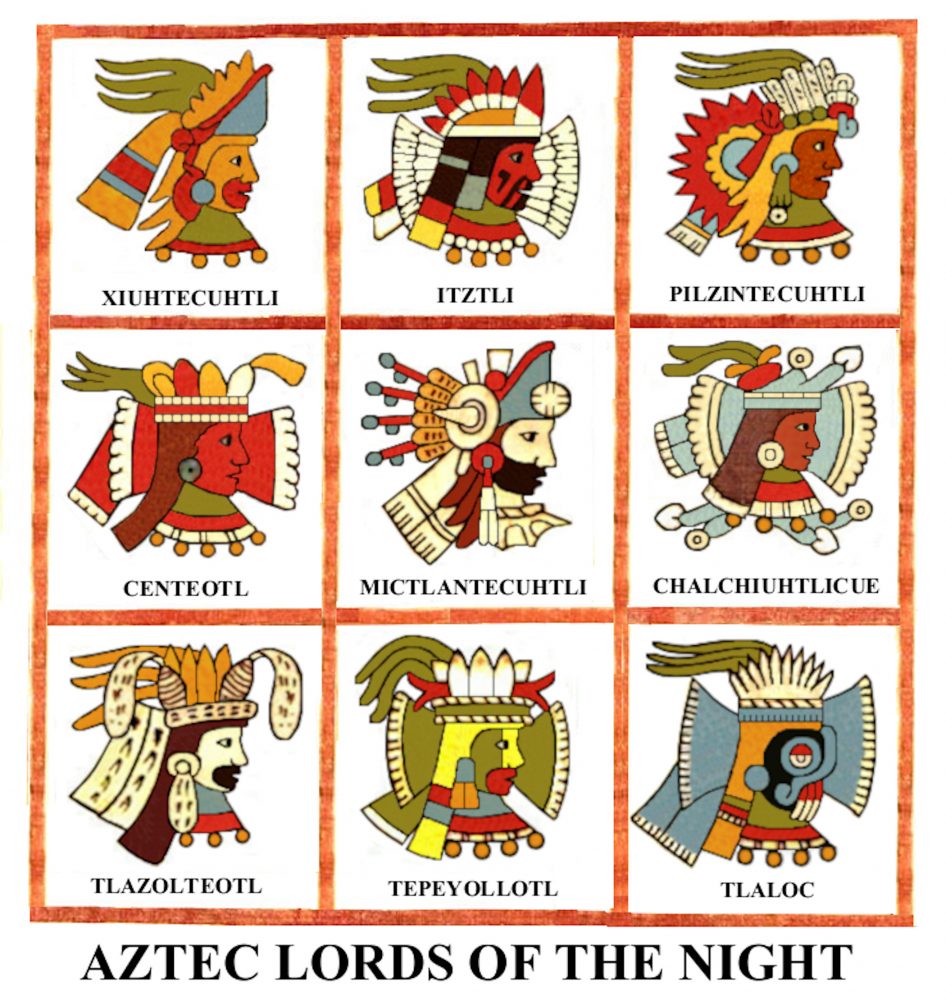

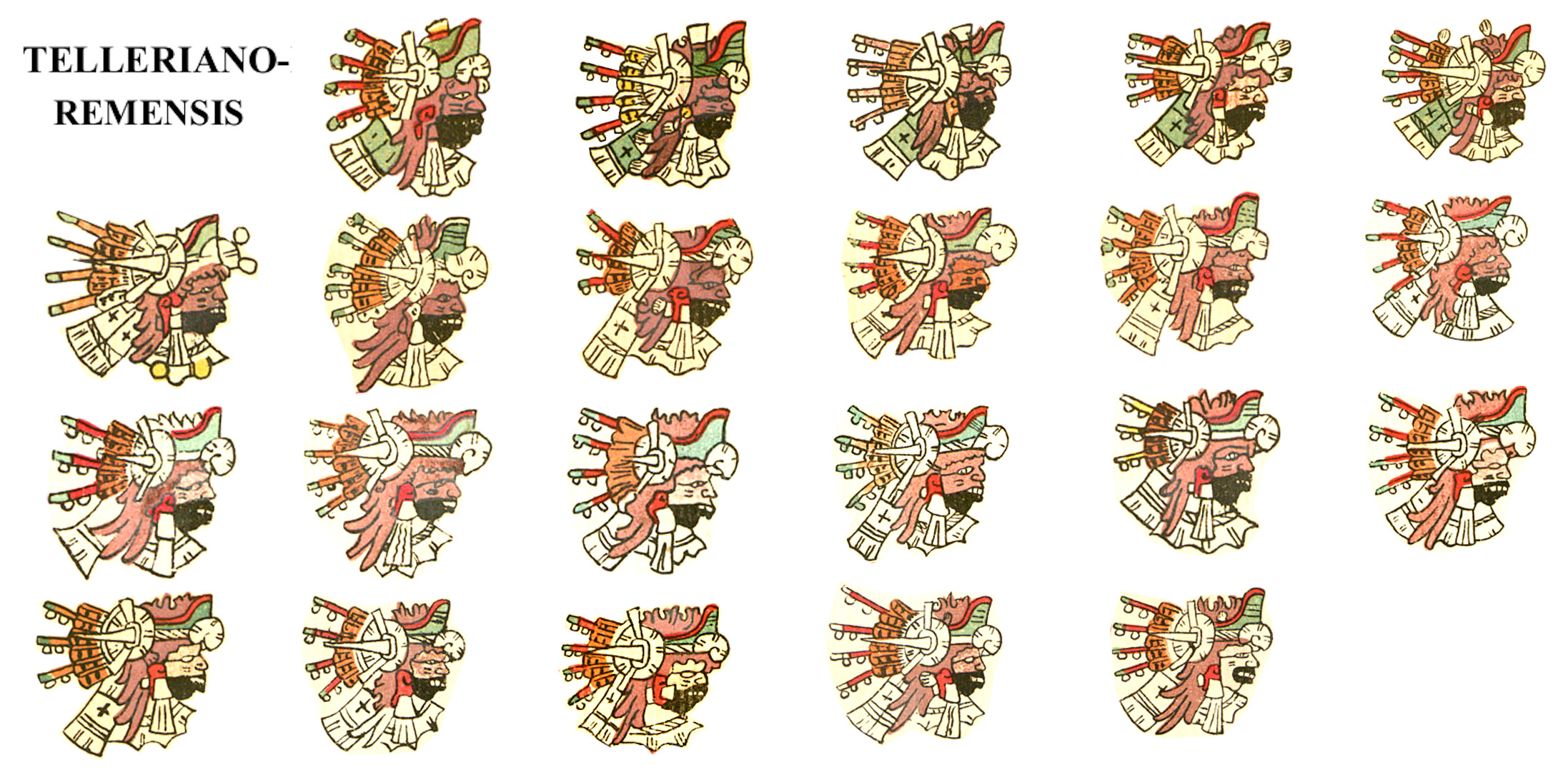

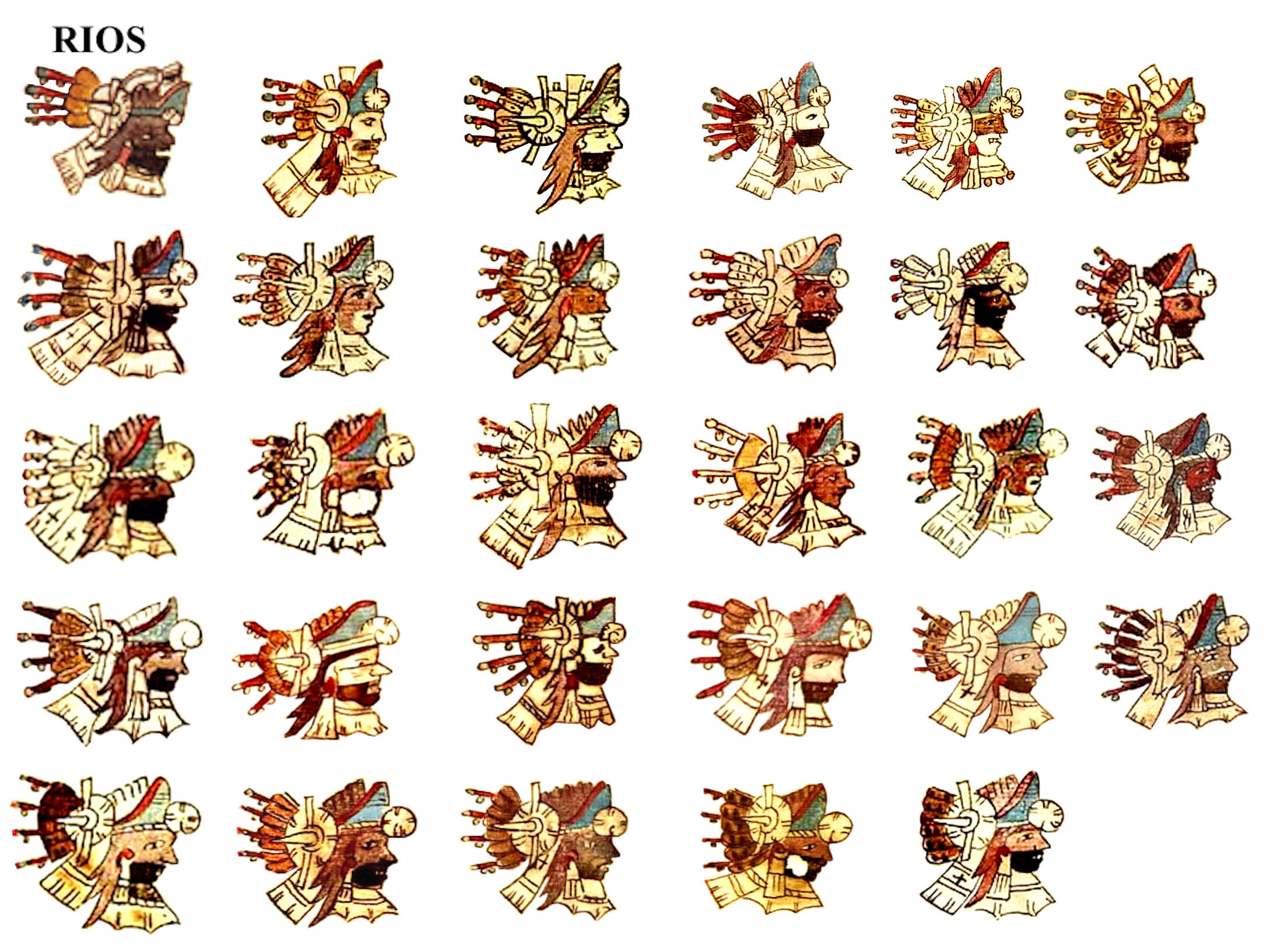

In tandem with my Tonalamatl Borgia re-creations, I’m also compiling and re-creating the trecenas from the related Telleriano-Remensis and Rios codices, which both present them on two separate pages. The latter codex is a later 16th-century Italian (slap-dash) copy of the (awkwardly sketchy) former document, and my compiled re-creation attempts visually sophisticated images of their unique day-signs and deities. As this Book of Days also includes the cycle of the nine Lords of the Night, I’m calling it the Tonalamatl Yoal (Night).

As the various trecenas of the Tonalamatls Borgia and Yoal are completed, I’ll post them along with those from my 1993 Tonalamatl Balthazar, present Dr. Paquin’s notes on their auguries, and remark on their iconography.

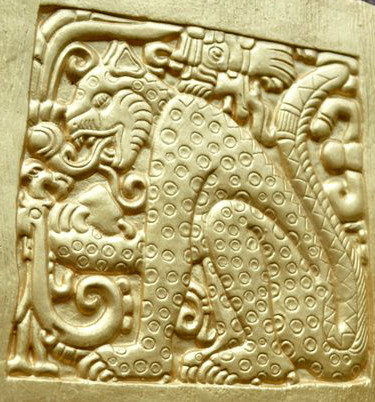

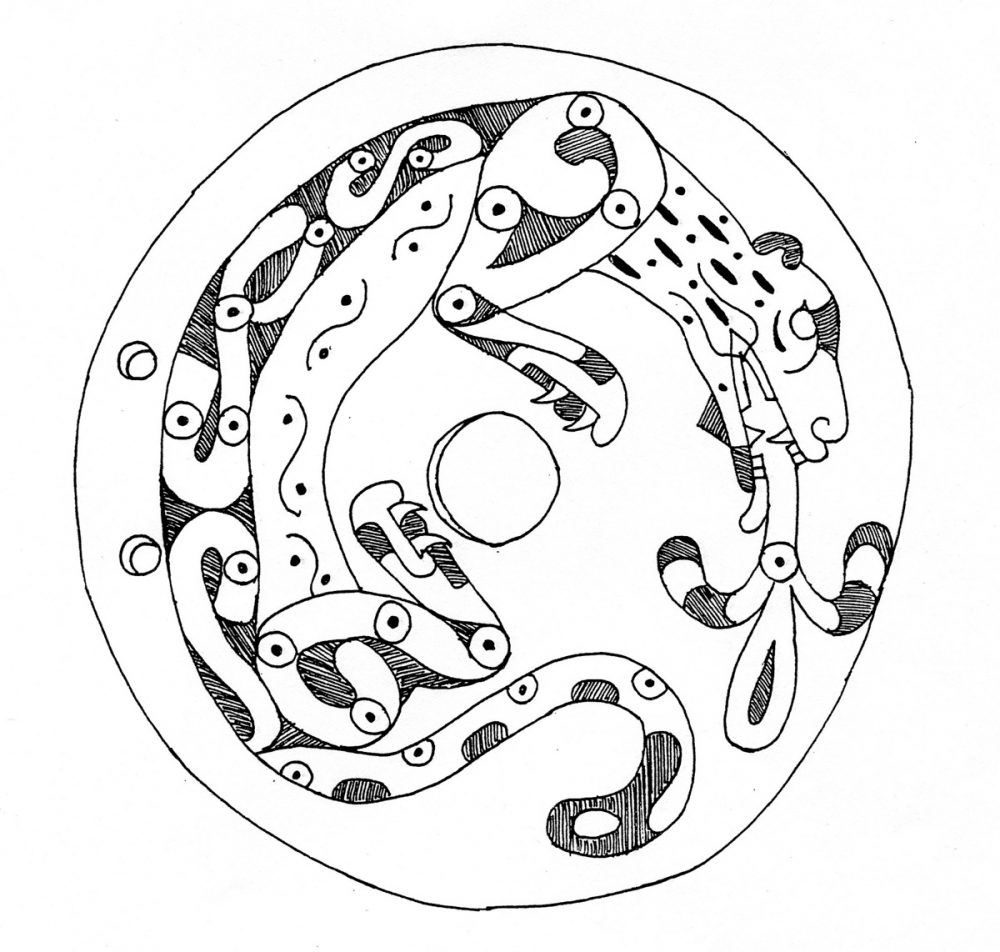

The obsession endures. When I’ve completed the Tonalamatls (should I live that long), I intend to create another series of 20 icons, this time in color—of the day-signs with their patrons and divinatory details. After that (if the creek don’t rise), I plan to build a complete mandala of the complex Aztec concept of time and space.

#