The fourteenth trecena (13-day “week”) of the Aztec Tonalpohualli (ceremonial count of days) is called Dog for its first numbered day, which is the 10th day of the veintena (20-day “month”). In the Nahuatl language, Dog is Itzcuintli, and it’s known as Ok in Yucatec Maya and Tz’i’ in Quiché Maya.

Understandably, the day Dog is connected anatomically with the nose (i.e., the olfactory sense) and symbolizes protection, loyalty, companionship, comfort, compassion, watchfulness, and devotion. It guards households and lineages as well as the portal between worlds, conducting the sun through Underworld at night and leading souls of the dead to Mictlan. In those functions, Dog represents a light in the dark and night vision. As the psychopomp (guide) in Mictlan, that Dog is a breed called Xoloitzcuintli, the “Mexican hairless” dog, named for the dog-god Xolotl, also an Underworld figure. Meanwhile, the Xoloitzcuintli is Mexico’s national dog and a symbol of Mexico City. Per Fr. Duran’s 16th-century account, people born on a Dog day will be courageous and generous, ascend in the world, and have many children.

In line with the Dog’s duties in the Underworld, the patron of that day is Mictlantecuhtli, Lord of the Land of the Dead (See Icon #10), a patron of the Flint trecena.

PATRON DEITY RULING THE DOG TRECENA

The patron of the Dog Trecena is Xipe Totec, god of liberation, rebirth, and springtime. He’s the lord of nature, agriculture, and vegetation and patron of gold- and silver-smiths and the day Eagle. Counter-intuitively he’s the god that invented warfare. In another paradox, as lord of the sunset, Xipe Totec is called the Red Tezcatlipoca (a nagual of that god) but also seen—along with Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli (see Snake trecena)—as a god of the East. Symbolizing renewal, like an ear of maize stripped out of its husk, he (and his cult’s priests) often wore the skins of flayed sacrificial victims. He brings and cures rashes, boils, pimples, inflammations, and eye infections.

AUGURIES OF DOG TRECENA

By Marguerite Paquin, author of “Manual for the Soul: A Guide to the Energies of Life: How Sacred Mesoamerican Calendrics Reveal Patterns of Destiny”

https://whitepuppress.ca/manual-for-the-soul/

Overseen by the Lord of Renewal and the life-affirming Feathered Serpent, this fire-oriented trecena tends to be oriented around the renewal of leadership, the forging of new directions, and the restoration of life. One of the key symbols associated with this time frame is a dog holding a torch, bringing light into darkness and showing the way. As guidance, justice, and forgiveness tend to be prominent themes in this period, it’s a good time to slough off the old, burn away transgressions, and take steps towards new possibilities.

Further to how these energies connect with world events, see the Maya Count of Days Horoscope blog at whitepuppress.ca/horoscope/ Look for the Ok trecena.

THE 13 NUMBERED DAYS IN THE DOG TRECENA

The Aztec Tonalpohualli, like the ancestral Maya calendar, is counted through the sequence of 20 named days of the agricultural “month” (veintena), of which there are 18 in the solar year. Starting with the 10th day of the current veintena, 1 Dog, this trecena counts: 2 Monkey, 3 Grass, 4 Reed, 5 Jaguar, 6 Eagle, 7 Vulture, 8 Earthquake, 9 Flint, 10 Rain, 11 Flower, 12 Crocodile, and 13 Wind.

Special days in the Dog trecena:

One Dog (in Nahuatl Ce Itzcuintli)—According to the Florentine Codex, this was a great feast day dedicated to Xiuhtecuhtli, the lord of fire, when people fed the fire with offerings (including decorative paper arrays) and incense. On this day rulers were elected, a court of justice sentenced wrong-doers, and minor offenders were released and absolved of transgressions.

Four Reed (in Nahuatl Nahui Acatl) was known as “the ruler’s day sign,” the day when new lords and rulers were installed, and tribute was paid to them. It was also a propitious day for the drilling of a New Fire because nahui acatl also meant “fire drills in all 4 directions.”

THE TONALAMATL (BOOK OF DAYS)

Several of the surviving so-called Aztec codices (some originating from other cultures like the Mixtec) have Tonalamatl sections laying out the trecenas of the Tonalpohualli on separate pages. In Codex Borbonicus and Tonalamatl Aubin, the first two pages are missing; Codex Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Rios are each lacking various pages (fortunately not the same ones); and in Codex Borgia and Codex Vaticanus all 20 pages are extant. (The Tonalpohualli is also presented in a spread-sheet fashion in Codex Borgia, Codex Vaticanus, and Codex Cospi, but that format apparently serves other purposes.)

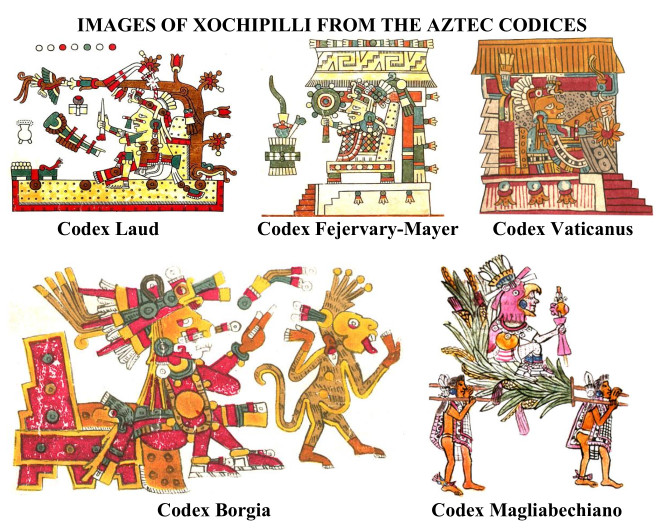

TONALAMATL BALTHAZAR

As described in my earlier blog The Aztec Calendar – My Obsession, some thirty years ago—on the basis of very limited ethnographic information and iconographic models —I presumed to create my own version of a Tonalamatl, publishing it in 1993 as Celebrate Native America!

In my image of Xipe Totec, modelled on Codex Borbonicus (see below), I stuck close to its form but in my ignorant enthusiasm played with psychedelic colors that broke iconographic traditions. Instead of the usual yellow or brown flayed skin and red body, I chose a dramatic red skin and white body; unaware of the cultural significance of his green quetzal plumes, I gave him multi-colored crests; and rather than his standard red-and-white streamers and scarf, I fancied him up with wildly colorful decorations. Note the sunset scene on his back-flap, the eagle on his shield (as patron of that day-sign), and other unwitting departures from tradition. Inspired by the spring connection, I gave him a nice “bouquet” of greenery to hold, indicating his lordship of nature and vegetation. Despite all the heresies (blasphemies?), I think my Xipe Totec is a great vision of this outrageous divinity. Now for some “dogmatic” views.

#

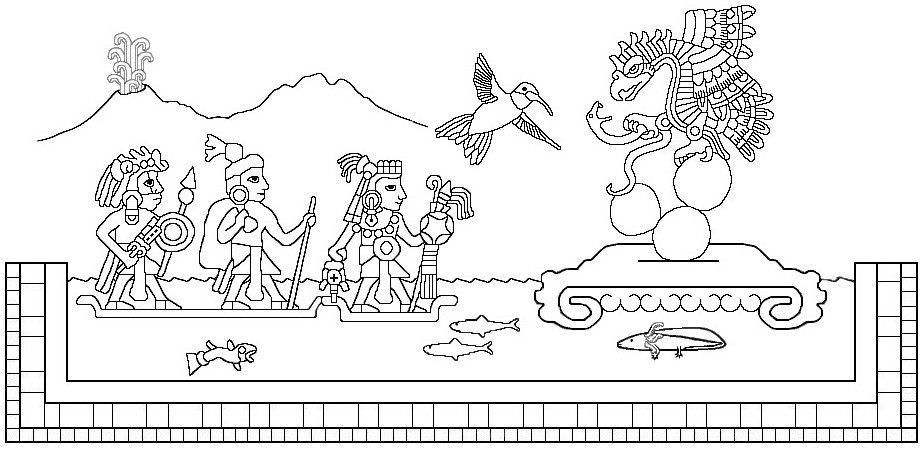

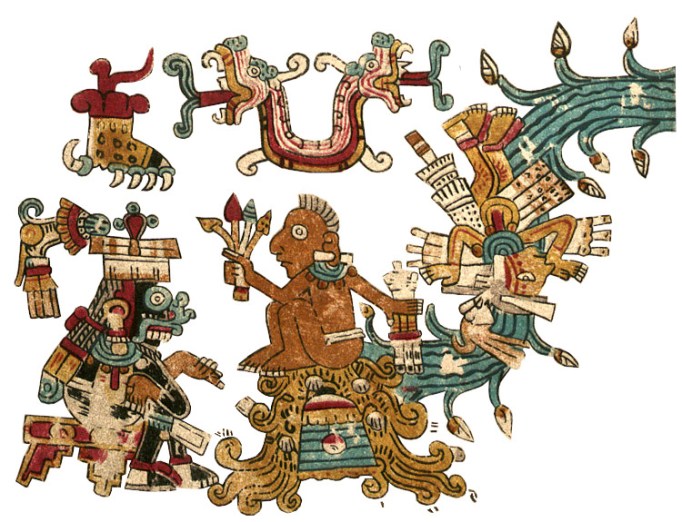

TONALAMATL BORGIA (re-created by Richard Balthazar from Codex Borgia)

Though this elegant Borgia image of Xipe Totec on the left doesn’t wear a victim’s flayed skin, he displays his standard red-and-white accessories. Some other traditional motifs are the convex red curve down his face and the bundle of arrows in his hand (signaling his connection to warfare and lordship). Most unusual is his stupendous crown, unlike anything I’ve ever seen elsewhere on any deity. His strange Y-shaped nosepiece only occurs in some of his Borgia portraits (including in the final Rabbit trecena). It’s another unique puzzle.

Amongst the ritual items in the center of this panel, the pointed red-and-white striped scepter is an emblem of Xipe Totec in his images in many codices. In some, it’s a full-scale staff with one or two points and in some the circular motif is an open oblong shape. Beyond a diagnostic of this deity, I’ve yet to figure out the significance of this scepter/staff and probably never will.

The figure on the right Dr. Paquin and many scholars see as a Feathered Serpent (Quetzalcoatl), a deity of “many faces.” (See Icon #14). I find it puzzling, first because if it’s supposed to be “life-affirming,” why is it eating the little guy? That doesn’t seem to embody the trecena’s theme of forgiveness. But I mostly question why it has a claw-footed leg (one only!) and a crocodilian head (without a snake’s fangs). Frankly, it looks to me more like an Earth Monster (Cipactli) shown often in the codices with a single leg and crocodilian snout and representing the mouth of the Underworld which both devours and produces life. That ties in well with the themes of renewal and rebirth. Another interpretation is that it may be a fire-serpent (Xiuhcoatl) relating to Xipe Totec’s militarism. In any case, I won’t presume to decide this eminently debatable issue.

Looking for an answer to the puzzle of that Y-shaped nosepiece, I checked out other images of Xipe Totec and found another Borgia portrait of him as patron of the day Eagle.

Imagine my revulsion to see him holding a severed arm, the hand pinching his nose as though to block a stench. In fact, the wearing of a (rotting) human skin must have stunk to high heaven. Like a clothespin, that Y-shaped nosepiece must have served the same purpose. And then just imagine my surprise to see again in the upper register the one-clawed serpent, this time either eating or spitting out a rabbit. As the parallel day-Eagle patron panel in Codex Vaticanus portrays these very same motifs, there must be a deeper relationship between Xipe Totec and the ambiguous creature beyond their companionship in the Dog trecena. Again, renewal and rebirth?

#

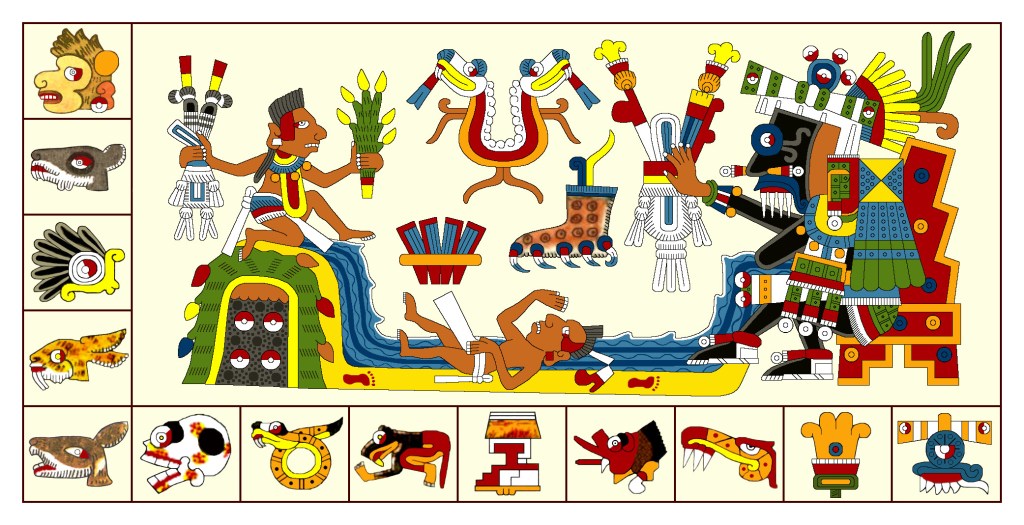

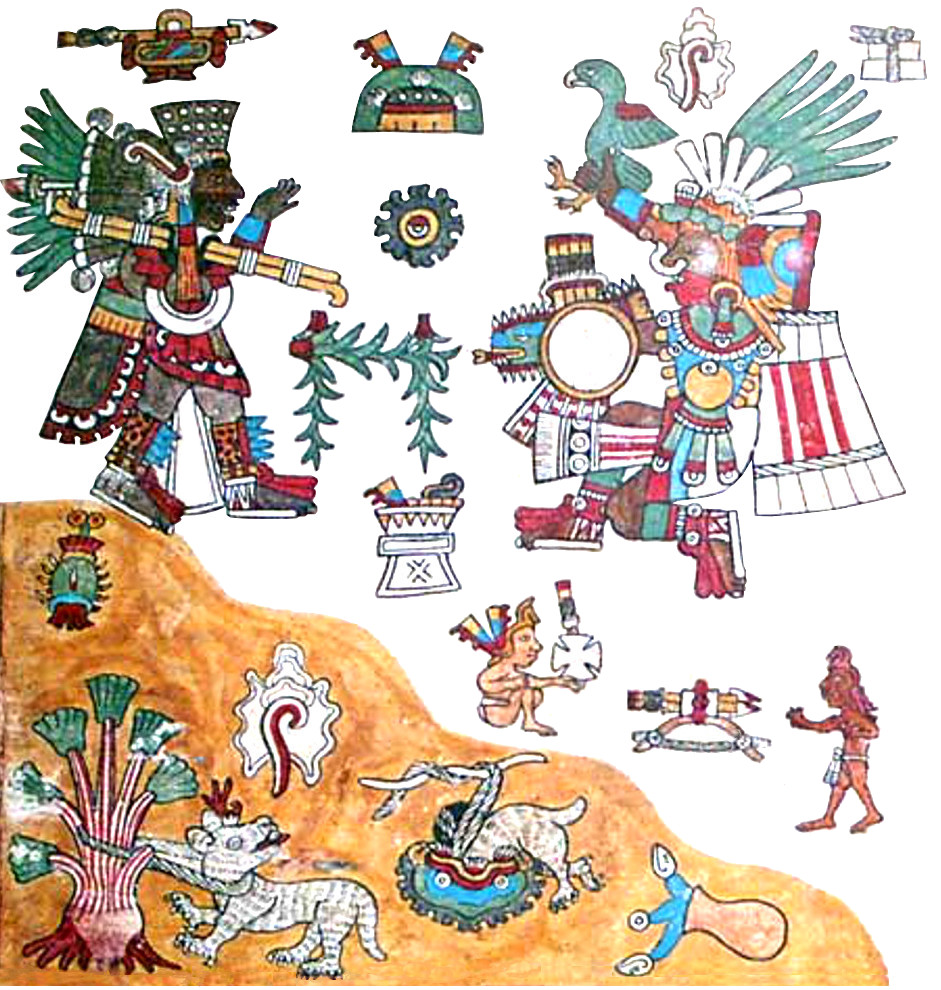

TONALAMATL YOAL (compiled and re-created by Richard Balthazar on the basis of

Codex Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Rios)

This dramatic image on the right is virtually identical in both source codices, a plumed, legless serpent devouring a little guy. Its head looks more like a snake, but it still lacks a serpent’s fangs. No doubt this is the good reason scholars see it as the Feathered Serpent (Quetzalcoatl). The discrepancy may lie in slight doctrinal differences between the areas where the codices were drawn, but either way, I figure the creature/deity still represents renewal and rebirth.

On the other hand, in terms of iconographic detail, the figure of Xipe Totec on the left is much more “dogmatic” than those in Borgia. In particular, he wears the (stinky) flayed skin, here in a pale yellow like that worn by Tlazolteotl in the Earthquake trecena, and I’ve given him the brown eagle-feathered skirt which Rios will give him later in the Rabbit trecena.

Most intriguing is his shield with the unusual, divided device, and I’m puzzled by the bundle of arrows (reeds) without arrow heads. Since his Telleriano-Remensis page is missing, I had to rely on the Rios copy, and instead of its murky brownish tones, I’ve colored many of his ornaments in his trademark red-and-white. My big question is how come, when Xipe Totec isn’t a lord of the day, he’s holding a totem bird? Such a blue bird is normally brandished by Xiuhtecuhtli, but in that case it should more properly be a blue hummingbird and not a parrot. I suppose this might simply be another instance of doctrinal difference—or iconographic confusion.

#

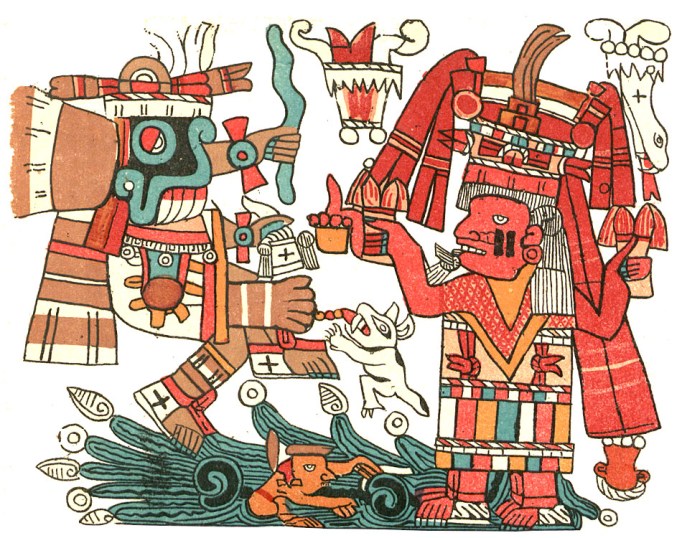

OTHER TONALAMATLS

Speaking of iconographic confusion, in this patron panel from Tonalamatl Aubin, the expected Feathered Serpent or Earth Monster is now a hungry (fanged) blob of eagle feathers, so we can’t tell which it’s meant to be. Xipe Totec here wears another flayed skin and more brown eagle feathers and carries a shield with a divided device, different than the one in Yoal but similar.

Note the dog behind his head for the trecena, the eagle in the upper left for his day, and that extraneous blue-beaked bird-head. Apropos extraneous, what’s that “Four Earthquake” day-sign on the left? That’s the name of the current Fifth Sun, and Xipe Totec has no connection to that legend. Even more inexplicable is the number eight at the bottom unattached to any day-sign.

#

Here’s the Codex Borbonicus model for my trippy Xipe Totec. Even without my psychedelic colors, he’s at least as dramatic and much more authentically detailed. One thing I didn’t understand in my version was the smoking mirror on his head (symbolic of his being the Red Tezcatlipoca). I didn’t and still don’t recognize the scepter in this image, and that was another excuse for giving mine the bouquet of greenery.

The odd little symbol on the banner is totally unfamiliar, but it must be rather important being attached to the concentric shield smack in the middle of the composition. A sort of two-legged ankh? Meanwhile, the One Dog day-sign attached to the shield makes sense for the trecena. Again, I’m mystified by the Four Earthquake day-sign attached to his foot and wonder if that Three Eagle day-sign might be his day-name. I haven’t run across any for him before.

Observe the suggestive bucket of blood by his left foot and the inscrutable item with ten dots and the peak of his traditional staff on top. In the upper right corner is a decapitated green parrot-like bird which I assume means birds may have been a premium sacrifice to the deity. (This detail may well explain that bird-head in the Aubin panel above.)

Since it has no leg at all, we probably should accept Xipe Totec’s plumed companion as the Feathered Serpent/Quetzalcoatl, a clue to that identity being the adjacent double-headed serpent seen in Quetzalcoatl’s headdress in the Jaguar trecena. However, this feathered creature’s head, nose, and dentition are distinctly feline. In any case, the mystical creature fits beautifully into the long history of images of the Plumed Serpent.

#

This patron panel from Codex Vaticanus I’ve rectified and restored slightly. Regarding Xipe Totec on the right, one wonders if the Vaticanus artist simply got on an easy “corpse-bundle” kick after Itztlacoliuhqui in the Lizard trecena and similarly bundling up Tlazolteotl in the Earthquake trecena. (The same funerary device will be used later for some reason for Xolotl in the Vulture trecena.) However, here I think it may signify Xipe Totec’s powers of rebirth. To be reborn, I suppose even a deity would have to die. Though he wears no emblematic regalia beyond the red stripe down his face, this god is well identified by his traditional candy-striped staff and standard bundle of arrows. On the left we once again find a one-legged Earth Monster reiterating the ambiguity of this subsidiary patron of the Dog trecena. For the purpose of divination, take your pick.

#

Something about these images of Xipe Totec troubles me. Namely, if he’s supposed to be the deity of springtime, nature, agriculture, and vegetation, there are no iconographic references to any of that. Apart from a suspiciously intimate relationship with the Earth Monster, all I see are military and lordship symbols. Perhaps the underlying message of nature is dramatized by the monster/serpent creature eating the little guy (and rabbit)—showing that philosophically speaking, life lives on life. Or if I might use a stronger, but still appropriate idiom: dog eat dog. So, my invented bouquet of greenery in the deity’s hand turns out to be quite apropos.

As for that ambiguous serpentine creature, I’ve concluded that its one leg is actually an epitome of intentional ideoplastic art. As remarked in the Jaguar trecena, that’s an image meant to be understood in intended detail rather than as optically accurate. Here the viewer’s quick brain automatically, unconsciously creates an invisible second leg immediately behind the one in front, a neat trick that makes drawing things in natural perspective conveniently unnecessary.

###

You can view all the calendar pages I’ve completed up to this point in the Tonalamatl gallery.