Significantly, in the Aztec calendar March 6, 2024, was the day Ome Acatl (Two Reed) and my 115th birthday in that ceremonial cycle of 260-day years. In our western calendar, I’ve recently celebrated my 81st birthday, wrapping up nine cycles of nine Gregorian years and starting in on my tenth cycle. The nine include a first inchoate period of childhood and eight discrete personas. For lack of a better description, I’m calling this new ninth persona the venerable iconographer, researcher, and/or historical theorist. We’ll just have to wait and see how that pans out.

This ninth Id-Entity will naturally continue my life-long focus on dance—ever since 1952 at the pudgy age of ten dancing in squares. My life of twinkling toes in many ethnic styles is amply discussed elsewhere. For at least 50 years, I’ve danced (mostly by myself) in an array of gay bars—the only place usually to find good dance rhythms—and in 2018, I discovered ecstatic dance. One moves as moved by the music, and the resulting ecstasy can be of a very spiritual nature, or at the very least psychically exhilarating.

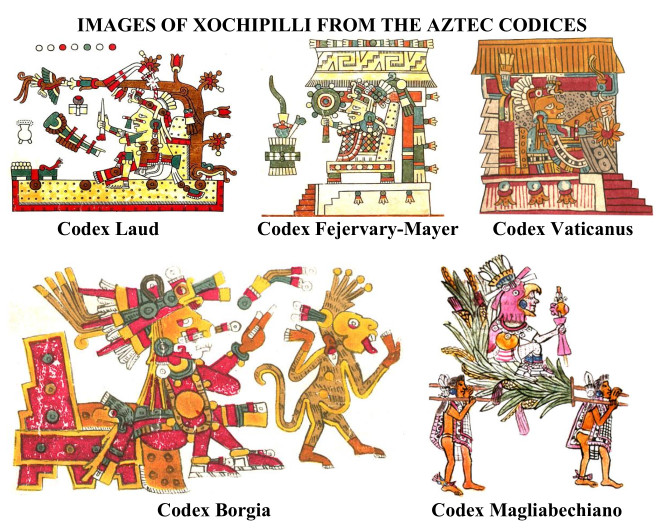

Understandably, after decades obsessed with Aztec mythology and iconography, in my dance ecstasy I quite naturally began to personify Aztec deities. For the summer of 2022, I got inspired to dance as Xochipilli, the Flower Prince. Here he is from my Icon #18 drawn in 2020, one of the few icon-details from my YE GODS! coloring book and exhibition that I personally colored. By the way, the monkey is because the Prince is the patron of the day Monkey in the calendar, and the parrot-headdress is emblematic of this god of fertility, crops, flowers, arts, festivity and pleasure (including dance—and sex!).

However, by August that year, I found myself dancing happily as Huehuecoyotl, the Old Coyote (See Icon #6 from 2015), the principal god of dance—and again sex (though for me this activity has been merely hypothetical for number of decades). In the drawing, he dances with rattle and scepter, and his regalia displays his patronage of feather-workers. I particularly love the wavy sound symbols of his howling but regret giving him that inappropriate tail. It’s too naturalistic and actually not at all iconographically authentic. This shape-shifting god was great fun to dance (and howl).

By early the next year, 2023, I started dancing ecstatically as Macuilxochitl (Five Flower), another god of dance and music and a famous manifestation of Xochipilli (a divine being called a nagual). Here he poses in a cameo detail from the 2020 Icon #18. His regalia is standard-issue divine finery, and instead of the hands on his loin-flaps, in traditional iconography, he should have a hand painted over his mouth. Odd fashion, but I didn’t have to wear any of this in our dance for the next several months.

By later last year, I began to realize that I myself was a nagual descendant of Huehuecoyotl—a new old-man deity ironically named Pilzincoyotl (Young Coyote). I began manifesting this divine Pilzincoyotl with rattle and fan in a drawing of an Aztec dancer. But as time went by, our divine lineage was revealed to me: a composite nagual of Xochipilli and Huehuecoyotl, born of a cross-species romantic liaison, on April 26, 1942, with the ceremonial day-name Ome Acatl (Two Reed). With that same day-name, Tezcatlipoca, the Smoking Mirror, is our powerful patron-godfather (See Icon #19).

Now, please understand that naguals only mature after living a full cycle of 52 solar years. So, we became a full-fledged nagual in 1994—just as I went back to a regular regimen of dancing. Our formal divination was by Tezcatlipoca on the day Ce Ollin (One Movement) in that year, ordaining us a deified spirit of dance. A half-cycle (26 years) later in 2020—just before the Pandemic—we were canonized as an official deity of dance with the rank of Quetzalcoyotl. Worshippers should address us as Ollintecuhtli, Lord of Motion, (esp. Earthquakes—when the earth itself dances), but you can just call us Quake.

Just last month, I finally completed my drawing of Pilzincoyotl, a self-portrait in neo-Aztec style. I should explain that at our ordination, we were also dubbed a deity of the rainbow, Cozamalotecuhtli. The fluttering curlicues are the sounds of the music for our divine dance.

Pilzincoyotl (Ce Ollin) Dancing in the Flower World

Please don’t think these are psychotic delusions. They’re not delusions but illusions, sur-realities. (Besides, reality itself is simply a construct of illusions.) Actually, my illusions of divinity may be psychotic, but they’re perfectly harmless. I don’t need anyone else to worship or believe in me. Just knowing I’m a god is plenty good enough. Precious few folks realize that they’re in fact deities.

###