Recently there have been a bunch of media stories about new twists on the out-of-Africa theories of the spread of early humans across the globe, and I’m surprised that invested anthropological authorities are actually considering alternatives to their sacrosanct interpretations about human history. Even more surprising is their grudging recognition that human populations seem to have left Asia and crossed Beringia into the Americas long before 12,000 BC, that set-in-stone date they gamble their scholarly reputations on.

It seems that writing history is actually a game of creating explanations to be assumed true until proven mistaken. In fact, like all things past or future, history is purely immanent—existing only in the mind, and that immanent universe is truly infinite, everything possible. Historians can guess with impunity about past events, and the burden of disproof lies with those who disagree.

I have no difficulty with human populations leaving Asia whenever and spreading south down the American continents (all the way to Tierra del Fuego!), nor with of dozens of primordial populations coming across oceans to the “New World” from Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. Scholars vociferously deny or simply ignore most of them. Recently, their denial of well-documented Pre-Columbian Viking voyages has been faltering—and they’ve started romanticizing these murderous marauders as handsome, heroic explorers. But you have only to read “The Farfarers” by Farley Mowat to learn the ugly truth about the rapacious Northmen.

Wherever they came from, it’s clear that roving bands of feral humans spread thickly across the American continents. For the most part, those populations seem to have settled permanently into their new locales like water filling low places. But there’s also been a great deal of sloshing around, overflowing into other catchments, draining in various directions, and even drying up or soaking into the earth, often leaving only their “ruins” and cultural artifacts.

My decades of interest in Panamerican prehistory have led me to learn of (and conjure up) some immanent cases of that inter- and intracontinental slosh of peoples on the move. I will now pull together what I think I know about the migrations and interchanges of peoples in the Americas. We need to discuss this immanently important, rarely mentioned subject. Let me begin.

#

Chapter I: The Pacific Littoral

The spectacularly long Pacific coastline (from Tierra del Fuego north to Alaska) has been a sailing route for millennia but is rarely mentioned by historians except for the travels of later European mariners/explorers. From earliest times, the peoples of Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia were seafarers, sailing the shores for fishing and trade. The route north to Mesoamerica is how the art of metalworking came there from the Andes and how the staple crop maize was taken south from Guatemala to South America.

Story #1: CIRCUMSTANTIAL EVIDENCE

Through geographical detective work, I deduced that boatloads of missionaries, merchants, and/or migrants from Chavín de Huantar in Peru (c. 1,500 BC) brought the sacred ceremonial calendar and other cultural concepts probably to Mesoamerica, possibly to ancient Izapa in Guatemala. From there, the complex is thought to have crossed the Isthmus of Tehuantepec into the Vera Cruz lowlands to the timeless Olmecs. I’ve already told this quite believable story in back in 2018.

Story #2: RELIABLE TESTIMONY

In the first millennium AD when the Maya civilization was in full Classic swing with warring kingdoms in Yucatan and Guatemala, I claim that refugee Maya peoples fled by boat along the Pacific littoral, settling at spots in western Mexico and farther north on the California and Pacific Northwest coasts. I base my claim on the report of Capt. Meriwether Lewis in “The Journals of Lewis and Clark” (ed. Bernard DeVoto) from March 19, 1805, where he wrote (sic!):

The Killamucks, Clatsops, Chinooks, Cathlahmahs, and Wâc-ki-a-cums resemble each other as well in their persons and dress as in their habits and manners. their complexion is not remarkable, being the usual copper brown of most of the tribes of North America. they are low in statu[r]e, reather diminutive, and illy shapen; poss[ess]ing thick broad flat feet, thick ankles, crooked legs wide mouths thick lips, nose moderately large, fleshey, wide at the extremity with large nostrils, black eyes and black coarse hair. their eyes are sometimes of a dark yellowish brown the puple black. the most remarkable trait in their physiognomy is the peculiar flatness and width of forehead which they artificially obtain by compressing the head between two boards while in a state of infancy and from which it never afterwards perfectly recovers. this is a custom among all the nations we have met with West of the Rocky mountains. I have observed the heads of many infants, after this singular bandage has been dismissed, or about the age of 10 or eleven months, that were not more than two inches thick about the upper edge of the forehead and reather thiner still higher. from the top of the head to the extremity of the nose is one straight line. this is done in order to give a greater width to the forehead, which they much admire. this process seems to be continued longer with their female than their mail children, and neither appear to suffer any pain from the operation. it is from this peculiar form of the head that the nations East of the Rocky mountains, call all the nations on this side, except the Aliohtans or snake Indians, by the generic name of Flatheads.

As others surely have, I’ll note Capt. Lewis has described here in exquisite detail the traditional Maya practice of skull deformation. It seems reasonable to me that this widespread cultural practice in the American West could have come from coastal colonies of refugee Maya. The also widespread practice of nose-piercing (as in the Nez Perce tribe and others) could just as easily have been brought by such “civilized” immigrants to the northern forests and mountains.

Story #3: A WILD GUESS

Toltec pressure and even later Aztec aggression no doubt also drove other peoples of western Mexico north in their boats along the ancient Maya route to the Pacific Northwest. I base this intuitive hunch on a linguistic coincidence (which I usually tend to dismiss).

The city of Seattle was named for the “chief” of a Native American tribe on the Olympic Peninsula. Phonetically, “Seattle” amounts to se-atl, and Ce Atl is the Nahuatl day-name (One Water) of the goddess of water, Chalchiuhtlicue, the Jade Skirt. As a name for a “town” or chief, One Water seems quite appropriate for a Nahua “colony” in that eminently watery area. But again, I’ve already told this and Story #2 back in 2018.

DNA tests should be run on Northwest tribes to look for markers of Mesoamerican populations. It would also make sense to compare the languages of those tribes with those of Mesoamerican peoples. (There’s a distinctly Nahuatl-ish sound to the names of the Tlingit and Kwakiutl tribes.)

Story #4: AN EPIC ESCAPE

Let’s back up some centuries and return to the Andes. In book “Advanced Civilizations of Prehistoric America,” Frank Joseph, an independent researcher cold-shouldered by academics, discusses the Huari of the Lake Titicaca area (often called the Wari) and the neighboring Llacuaz people, observing that their principle currency was the spiny oyster Spondylus princeps shell.

That seashell was sometimes found along their coast, but their main source was from the distant north in the Sea of Cortez. In the latter centuries of the first millennium CE, Joseph proposes that these peoples sailed those thousands of miles to collect their “money” and meanwhile “explored” up the Colorado and Green Rivers across Arizona. The Llacuaz established colonies in the Green River basin, and the Huari pushed on into northwestern New Mexico where, by the early ninth century, they started building vast structures at Chaco Canyon.

Joseph suggests that when the Chimu (possibly Chinese!) invaded Peru c. 1,000 CE, establishing a civilization centered at Chan Chan, they drove the Huari and Llacuaz out of their Lake Titicaca home area. Many thousands of refugees boarded their reed boats and balsa rafts and fled north to their distant colonies in North America. The Llacuaz, superb hydrological engineers, became the Hohokam civilization—whose descendants are the Pima and Papago tribes.

The refugee Huari people must have exploded the population at Chaco Canyon, and these “Anasazi” spread out across the Four Corners area, an ancestral culture for the present-day Puebloan peoples. Joseph points out that Chaco architecture (like Pueblo Bonito) replicates their traditional styles in Peru—the D-shaped, multi-storied “apartment complexes” and particularly the round, sunken “kivas” which are now culturally central to their Puebloan descendants.

This is the only “origin story” I’ve found for the ancient civilizations of the American Southwest. Though it involves migration across mind-boggling distances (think of the vast spread of the Indo-Europeans out of Central Asia across Europe and India!), it makes ultimate sense and comes with some dramatic evidence. Until someone offers a better story, I’ll go with this one.

#

Chapter II: The Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea, enclosed by the archipelago of the Greater and Lesser Antilles, amounted to a prehistoric American “mediterranean” arena of cultures. Sea-faring peoples like the Maya of Mesoamerica and the Arawaks and Caribes of the South and Central American coasts roved around the basin, not unlike Old World traffic on its Mediterranean Sea.

Story #5: THE SANCTUARY

As well as along the Pacific littoral, Maya refugees from civil violence (like the Itza and other Maya peoples) also fled into the American Southeast. In Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and along the Gulf coast, they settled among resident “natives.” As early as 200 CE, the immigrants brought their mound/pyramid and artistic traditions, contributing to Mississippian culture. See my “Remember Native America!” and my ethnographic essay. I should note that the skull-deformation and nose-piercing mentioned above in Story #2 also occurred in many parts of the world, including among early immigrants into the American Southeast.

Another independent researcher (of Creek heritage), Richard Thornton, writes a blog called “The Americas Revealed,” which I’ve followed for several years. Though vociferously opposed and denied by academic authorities, he discusses the Maya, Arawaks, and Caribes also penetrating in early centuries into the Southeast, and as an accomplished city planner and archaeologist, he has modelled their traditional towns and architecture at archaeological sites in the area.

As well as the early Maya, Thornton says that later Mesoamericans such as the Totonacs and Huastecs also fled the depredations of Toltec and Aztec imperialists and trekked around the Gulf into the Southeast, adding their cultures into the melting pot that would produce the Native American stew of tribes like the Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Caddo, and others. Some retained legends of their migrations from specific locales in Mesoamerica.

In addition, citing serious linguistic evidence, Thornton says that a South American people called the Panoans migrated from Ecuador and Peru into the Southeast and brought their own seasoning into the melting pot. At first there seemed not to have been much friction or violence between the many disparate cultures, each group continuing their ethnic lifeways in their own immigrant communities. Densely scattered across the landscape, they were like the Maya’s decentralized urban pattern of town-states, some bonafide cities with pyramid/temple and plaza complexes.

#

Chapter III: Cross-Country Migrations

Thus far we’ve seen sea-rovers on the Pacific littoral and around the American Mediterranean Gulf, and now let’s talk about the land-roving folk within the continents. I know virtually nothing about peoples moving around in South America but suspect a considerable flow between the Amazonian and Pacific slopes of the Andes. However, I’ve just read somewhere that in distant millennia the first peoples of Mesoamerica migrated there from South America. I think they’re talking around 6,000 BP, so that sounds perfectly feasible. Why not?

Story #6: LATECOMERS

Meanwhile, I do know bits and pieces about the land-rovers of North America (besides all that about primordial folk from Asia spreading south through the continents). One bit is a widely discussed issue in American archaeology: Very late, around 13-1400 AD, a small group of Athabaskans (originally of course from Siberia) left their subarctic home in far northwest North America and migrated into the American Southwest, specifically into the Four Corners area, to become today’s Navajo and Apache tribes.

Strategically, these Athabaskans arrived soon after the Chaco civilization “disappeared,” and they were bitter enemies of the remnant populations of Anasazi, the Pueblos along the Rio Grande, and the Hopi in Arizona. In view of this historical migration, I find it curious that Navajo mythology has that people emerging from under the earth somewhere, maybe near Shiprock (a volcanic core mountain) in northwestern New Mexico. However, many peoples the world over claim to have come into this world from the underworld.

Story #7: THE STEW

Meanwhile, in the same centuries, as the Mississippian civilization in the American Southeast (and the Caribe kingdoms in the Antilles) grew more warlike with rival city-states (much like the earlier Maya situation perhaps), various peoples moved around to elude their oppressors. Many migrated across the Mississippi River onto the plains. Thornton tells of the People of the Eagle (Kansa) from central Georgia who moved into what would become Kansas.

By the early 1600s, under pressures of aggressive neighbors and newcoming land-hungry European invaders, some Mississippian folks evacuated the Carolina coast and moved way out onto the plains of the Dakotas. In that strange new environment, they mastered the Europeans’ horse culture and became the Sioux, the quintessential Plains Indian.

Over the centuries, many other ethnic communities in the vast Southeastern woodlands certainly must have upped and gone somewhere else for whatever reason, stirring up the stew of peoples. For instance, in the early 18th century various Southeastern peoples pressed south into La Florida (by then thoroughly depopulated by disease and Spanish occupation) to become the Seminoles.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, probably inspired by contacts with European concepts, many polities in the central Southeast coalesced into the Creek Confederacy, which for a long time constituted an autonomous “country” west of the European colonies along the Atlantic coast. After battling these “Five Civilized Tribes” for several years in the Creek (and Seminole) Wars, General Andrew Jackson became President of the US of A and in one of the hugest land-grabs in history, exiled the Southeastern peoples to the new “Indian Territory,” part of the recent Louisiana Purchase. Between 1830 and 1850, some 60,000 native people took the Trail of Tears hundreds of miles west to Oklahoma, a forced migration on which thousands died.

During the 18th century, before the coastal European colonies had fully occupied Appalachia, a large tribe from the Canadian Maritimes spread south down the mountain chain and by late in the century had encountered the confederated tribes, probably with considerable friction. These were the Cherokee, who now claim to have lived in the Southeast “for thousands of years” and would usurp the history of the diverse “native” tribes. Indeed, some Cherokee joined them on the Trail of Tears. Those remaining in the western Carolinas and elsewhere soon were accepted by the US of A as a “civilized” (pacified) tribe, and in turn they accepted the new country’s dominion.

Story #8: RITUAL JOURNEYS

The culture and cosmology of the Hopi people, an affiliation of several clans now living in northeastern Arizona, is based on migrations. A legend has them migrating from somewhere in the far south, either South America, Central America, or Mexico. In the first case, they may have left Peru along with the Huari and Llacuaz refugees (Story #4), having settled on the desert mesas at roughly the same time in the late first millennium CE when the others were colonizing southern Arizona and Chaco Canyon. Significantly, Hopi architecture with its multi-storied communal dwellings and circular kivas closely reflects Chaco traditions.

Coincidentally, their migration seems also to have involved a long ocean voyage, but some folks theorize that the Hopi sailed all the way from Asia or elsewhere. For linguistic reasons, I incline to the Peruvian story. We don’t know what language was spoken by the immigrant Chaco people, but I bet it was one of the Uto-Aztecan family—since the linguistically related Utes and Shoshoni tribes were likely early offshoots of the Chaco civilization, and the Hopi language is also Uto-Aztecan. (I’m not sure how the Puebloan languages would fit into this matrix.)

On another hand, in the same way as the Navajo and many other peoples, the Hopi “mythology” has their clans emerging from a hole in the earth (cave?) called the “sipapu” located somewhere near those same desert mesas. Then their principle deity Masau-u then sent the many clans on individual ritual migrations to the four ends of the earth and back in order to find their promised land. Surprisingly, after hiking from seas to shining seas, the clans eventually converged again on those same desolate mesas, founding their town of Oraibi around 1100 CE.

Each migrating to the four ends of the earth, the several Hopi clans must have encountered many other peoples, like the Toltecs in Mexico and the Mississippian cities in the Southeast. The possible histories of cultural contacts are legion. Meanwhile, those migrating clans often left petroglyphic evidence of their passing through many areas with their identifying symbols.

Story #9: LEGENDARY MIGRATION

When I ran across “The History of the Indies of New Spain” by Fr. Diego Durán (1537-1588) around 50 years ago, I was enchanted by his detailed account of the legendary migration of the Aztecs into Anahuac (the Valley of Mexico).

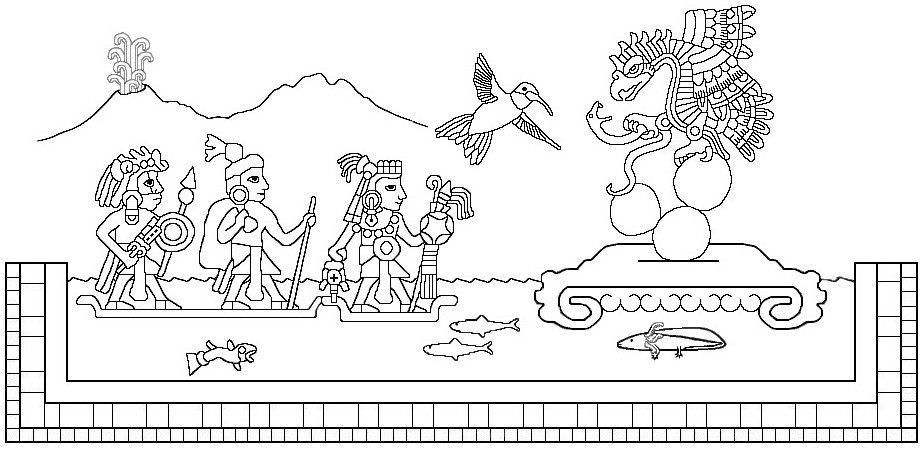

The migration legend is intertwined with the mythology of the Mexica’s main deity, the war god Huitzilopochtli, Hummingbird of the South. Leaving their previous home around 1200 CE, he led the Mexica migration for well over a century to finally find their promised land on a swampy island in Lake Texcoco in 1325 CE. Within a century, they’d built a huge city on that island called Tenochtitlan, Place of the Cactus, and had begun assembling an empire based on trade and military might—which in 1519 fell victim to Cortez and his Spanish conquistadores.

The legend describes the impossibly violent birth of Huitzilopochtli at a place where the Mexica were living called Chicomoztoc (Seven Caves) and his autocratic and arbitrary leadership of the nomadic migrants, who settled down in various places for lengthy periods to sow and harvest crops. On their travels, they pillaged the “Red City” (possibly the site in Chihuahua known as Casas Grandes or Paquimé), and they vandalized many resident populations, gaining a reputation as utterly uncivilized barbarians. For an egregiously atrocious offense against the ruler of a city on the lake, they were driven out onto the island where they found the prophesied eagle on a cactus eating a snake. That iconic image is now an official symbol of the Mexican state.

It’s intriguing to know that during their migration and in Anahuac, the Mexica spoke essentially the same language as resident populations, a dialect of Nahuatl—because those peoples had earlier also migrated south from Chicomoztoc. Duran tells us that by 820 CE the first six “nations” (tribes or clans) started sequentially leaving the Seven Caves: the Xochimilca, Chalca, Tecpanecs, Colhua, Tlalhuica, and Tlaxcalans. Settled down again after long wanderings, the several clans established large cities around Lake Texcoco and in various other central areas of Mexico. The Mexica were just the long last tribe to leave the Caves.

This shared history of migration seems to say that the language of the Chaco civilization must have in fact been (as suggested in Story #8) Uto-Aztecan, another dialect of Nahuatl, and it raises again the question of the Huari (Peruvian) language. That question gets complicated by the fact that the Toltec civilization (900-1160 CE) also spoke Nahuatl. An “empire” centered at Tula just north of Lake Texcoco and at Chichen Itza in the Yucatan, they could have also been migrants from the far north—or just as easily, like Chaco, an early invasion or colonization of Huari from Peru, refugees or otherwise. The time frames suggest maybe the earlier Seven Caves migrants had a hand in the destruction of the Toltecs. Remember, history is but an immanent story.

This is not to imply that Chicomoztoc might have been Chaco Canyon. At Chaco, there may have been seven great-house pueblos, but they were nothing like caves. My radical theory is that Chicomoztoc was the several cliff-dwelling towns of Mesa Verde, a major outlier of the Chaco civilization with a real road connecting the centers. That makes vastly more sense to me than the mound-site in Wisconsin ridiculously called Aztalan or some vague spot lost in the deserts of Sonora/Chichimeca. Until someone can convince me otherwise, I’ll go with Mesa Verde.

A deeper legend has the Mexica (and other tribes) coming originally from a place called Aztlan, a “place of whiteness” or “place of herons.” Some speculate it’s somewhere in northwestern Mexico or the American Southwest. In that legend, the peoples lived at a large lake and were driven out by enemies, forced to make a long sea-voyage and then wander lost in deserts—before finally getting to Chicomoztoc. This “place of herons” scenario closely parallels the Huari fleeing before the Chimu from Lake Titicaca to Chaco, and if Chicomoztoc was in fact Mesa Verde, all the puzzle pieces fall neatly into place. Ergo, Aztlan looks like it was Lake Titicaca, and the Huari probably spoke a version of Nahuatl. That story works just fine for me.

#

Epilogue

In Story #7: The Stew, I unavoidably remarked on some migrations spurred by cultural pressure of post-Columbian European invaders, like that of the Sioux and the tragic Trail of Tears in the 19th century, but the countless forced migrations of native peoples in recent centuries (like the Navajo to Bosque Redondo) are far more than I can bear to think about.

When Cristóbal Colón arrived in 1492, he and his family immediately started colón-izing the indigenes of the Greater Antilles (Cuba, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and Hispaniola) by enslaving, slaughtering, and driving them to escape into the interiors of North and South America. As soon as they were decimated or totally wiped out, black slaves were imported from Africa to work the Spanish mines and sugar plantations on the islands. This was just the first small step in the European displacement and destruction of native populations across the American hemisphere.

###