The Translator’s View by Richard Balthazar

Statue of Joan of Arc in New Orleans

On the 100th anniversary of her canonization, St. Joan of Arc appeared in New Orleans in a miraculous vision to the fortunate multitudes in the 2,100-seat Mahalia Jackson Theater, and I was privileged to be among them. The New Orleans Opera Association’s production of Tchaikovsky’s “Joan of Arc” was presented there February 7 & 9, 2020 under the artistic direction and musical baton of Maestro Robert Lyall. For the unfortunate multitudes who couldn’t be there to experience Joan’s epiphany, I want tell you all about it.

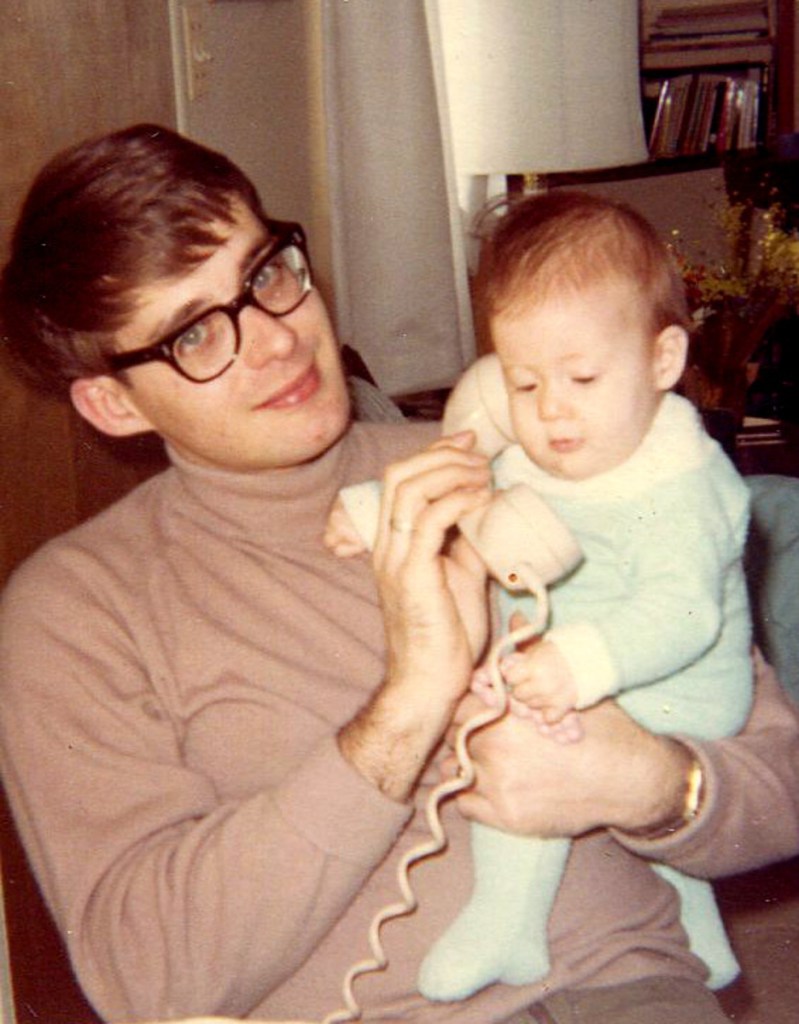

As the translator of Tchaikovsky’s Russian libretto of “Joan of Arc” into English, I’m probably as close as anybody alive to this work. The first translation was done for performances by the Canadian Opera Company in 1978, and though I thoroughly revised it afterwards, Michigan Opera Theatre used the first version for their 1979 production in Detroit. For New Orleans Opera Association’s production in 2020, I substantially revised it yet again.

Having seen the two earlier productions, I feel eminently qualified to critique the New Orleans production. “Maid of Orleans,” or “Joan of Arc,” was the composer’s foray into the field of French Grand Opera, and in my humble opinion, its grandiosity is incomparable. Connoisseurs of the genre, please feel free to differ…

As a Russian scholar, I’ll just say that in my translation the music sounds like it was written for my straight-forward and poetic English words, rather than for Tchaikovsky’s convoluted, many-syllabled Russian syntax. But I also thank Maestro Lyall for his superb edits smoothing out rough edges and much improving the “sing-ability” of some phrases.

In the same vein, I applaud Lyall for masterfully abridging Tchaikovsky’s sprawling libretto (which if performed in its entirety, would run for well over four hours!), into two hours and forty minutes of magnificent music and inspired drama. I also applaud his clever use of supertitles during overtures and entr’actes with brief texts to set true historical contexts and to link the disparate scenes into a cohesive narrative and easily followed story.

This translator’s view will be largely that of a discerning audience member with a long life in theater and opera. Necessarily, I’ll have to leave detailed musical analysis to the musicologists, but I’ll strive for objectivity in my descriptions.

The Production

In the four acts of the opera, scenes were all framed simply but ornately as though they were paintings. (In his libretto, Tchaikovsky called the Scenes “Pictures.”) The sets in the Pictures were pleasantly simple and effective, abstract constructions of planks and platforms—call it “plank and platform style,” adaptable and easy to alternate and to execute rapid scene changes.

The backdrops were beautifully “painterly.” That in the first act was particularly so with a hazy landscape and only an outline of a small church that was very symbolic. In later pictures we saw an elegant stained-glass window and then a vast iconic painting of a woman’s face. I thought at first it was Joan, but considering the halo, it made more sense for it to be the Virgin Mary. Whichever, it was an appropriately religious symbol and I hope Scenic Designer Steven C. Kemp is justly proud of his success!

The noted Stage Director, Jose Maria Condemi, should also take pride in his smooth handling of the numerous large crowd scenes and of his sensitive direction of the characters’ movements and interactions within the Pictures. The tableaux, ranging from pastoral to ornate cathedral, were beautifully composed, and all very subtly yet dramatically lit by Lighting Designer Don Darnutzer. Maybe it won’t be a spoiler if I praise his fiery pyre in the opera’s finale.

Joan of Arc at the stake – Photo: Brittney Werner

Let me offer my sincere compliment for the fantastic musicians of the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra, directed by Maestro Lyall. They poured Tchaikovsky’s immortal music out over the audience in powerful and heart-wrenching waves. While not a qualified music critic, I can only observe that it sounded really great!

But I do have more than a few clues about some other things. In my past I did a bit of Russian vocal coaching for singers (and for the Paul Hill Chorale to sing Kabalevsky’s “Requiem”). An important component of “Joan of Arc” is that it’s an enormously “choral” opera. Those large crowds mentioned earlier belted out several numbers that rattled the rafters, laments, prayers, fight songs, triumphal marches… What really blew me away was the Hymn in Act One. Prepared by Chorus Master Carol Rausch, the opera chorus sang with remarkable clarity and precision, delicately modulated to balance with the soloists, yet with startling power.

Having been in my long ago past an extra in the ballet “Coppelia” (and a life-long avocational dancer), I’ll claim to know about dance. The obligatory ballet number in Act Two was truly what the King ordered, a jolly entertainment, and likely a lot jollier and sprightlier than it would have been at any French court six hundred years ago. Choreographer Gretchen Erickson melded three superb dancers into an exciting athletic, even gymnastic, frolic. Of the three ballet numbers Tchaikovsky wrote for the opera, Maestro Lyall definitely chose to include the jolliest.

I must also commend the Fight Director Mike Yahn for the various sword fights and attendant mayhem. Avoiding flashy displays, he kept the violence to a realistic and convincing minimum, the way people actually try to stab each other with swords. And I’ll wind up my remarks on the physical production by praising the beautifully detailed period costumes for the peasants, nobles, and military, created by the talented Costumer Julie Winn. Joan’s armor alone was a marvelously medieval piece of work!

The Performances

As the heavenly-inspired peasant girl Joan of Arc, Hilary Ginther completely commanded the stage from the moment of her angelic inspiration through the triumphs, soul-wrenching romance, crushing tragedy and divine enlightenment to her ultimate immolation. This tiny but mighty mezzo Maid filled Mahalia’s huge house with the glory of her prophecies, prayers, spiritual anguish, religious fervor, heroic valor, tender love, and ultimate martyrdom. It is difficult to describe the glorious musicality of Ginther’s performance, but it was a tour de force, a true epiphany. I hope Joan of Arc can become this incredible artist’s signature role, and other opera companies should sign Hilary for many more productions of this masterpiece.

Blessing Joan to lead the troops – Photo: Brittney Werner

In commenting on tenor Casey Candebat’s performance as the Dauphin (King Charles VII), it’s hard not to resort to even more superlatives. In a word, he WAS superlative. With touching humanity, Casey’s rich, clear voice carried all the majesty, romance, and elements of Charles’ personal struggle between cowardice and bravery that Tchaikovsky had written into this role. His coronation address to Joan was a marvel of reverent adoration. Then, convinced by a few presumably divine claps of thunder, he, too, was swept up in the chorus’ orgy of fear and superstition. Abandoning Joan, he rushed off with his newly-won crown, ending the King’s role in her dramatic story that had been wonderfully sung.

Coronation of Charles VII – Photo: Brittney Werner

There are lots of other characters in this opera, and the performances of each and every one were outstanding.

The pivotal role of Thibaut, Joan’s father, was sung by bass Kevin Thompson who, as noted by others, has “a mountain of a voice.” That voice perfectly embodied the element of superstition on which the opera turns. Kevin’s remarkable bass voice, aided by those aforementioned divine thunderclaps, created a true avalanche of fear, hatred, and stupidity that swept Joan from her exalted heights into a pit of despair and exile—the ultimate parental guilt trip. No wonder that during the bows Kevin earned the audience’s heartfelt boos!

Soprano Elana Gleason, playing Agnès Sorel, the King’s affectionate mistress, expertly delivered her extremely difficult love arietta with the King—with its very high notes!—with great delicacy and tenderness. We should all have such generous mistresses!

The role of Dunois, duc d’Orléans, was impressively fulfilled by dramatic baritone Michael Chioldi, who served as the conscience and inspiration for the King. In all of his scenes, Michael’s resonant voice drove the action, his nobility instilling courage and resolve. It is a complicated role with its aspects of conflicting loyalty and heroic determination.

The role of the romantic male lead, the Burgundian knight Lionel, was performed by baritone Joshua Jeremiah. Lionel is a pivotal role, a man who turns from French traitor into passionate lover, who first abuses Joan as a demon and then becomes her protector. In the final love duet, Joshua’s heroic voice blended perfectly with Joan’s mezzo in praise of God’s heavenly gift of love. (Unfortunately, he had to die—but did so grandly.)

I was thrilled by bass Raymond Aceto’s Archbishop who narrated to the court with ecclesiastical majesty Joan’s first appearance with the French troops, her leading them into battle, and their victory over the English. Raymond’s every word was crystal clear and weighty with the miracle of it all. He brought the same musical authority to all his other scenes, whether urging the people to believe or interrogating Joan’s virtue, or even when proving to be just as stupidly superstitious as everybody else.

In Act One, Kameron Lopreore movingly played Raymond, a village suitor whom Joan rejected; his tenor solo line in the Hymn was sung with plaintive force. Bertrand, a peasant refugee, was sung with immense pathos by baritone Ken Weber, and his solo line in the Hymn was a profound lament. The unnamed Warrior played by baritone David Murray dramatically narrated his narrow escape from the battle of Orleans and confirmed Joan’s first prophecy. In Act Two a dying soldier named Loree was sung by Frank Convit. His lines urging the King to join the fray and his final words “I’ve done my duty now…” were sung with all the poignant power of a seasoned soloist. All four of these roles were expertly delivered.

Concluding Remarks

You’re probably wondering if the preceding descriptions can be called objective, but I assure you they were—I could find nothing even vaguely negative to say! But, though I’d love to say that the New Orleans production of “Joan of Arc” was flawless, I admit there was one challenging detail.

Three times Joan hears the heavenly voices, and the angelic messages are crucial to the very structure of the opera. First, they send her forth on her mission, and second, they proclaim her mission accomplished and call her to come to glory (where a virgin martyr’s crown awaits, as well as rapture in God’s divine embrace). Then, third, they welcome Joan into heaven.

The off-stage voices of the angels, necessarily somewhat muted and baffled by curtains, largely got drowned out, sometimes by the enthusiastic orchestration and at other times by competing vocal lines. Fortunately, the words appeared on the supertitle screen—albeit quite briefly—allowing audience members to some degree to follow what they were supposed to be hearing sung and to sort it out from the other competing vocal lines.

What I could hear of Julia Tuneberg’s lovely soprano was ethereal, but her single voice was mostly lost in the melee. If that was anyone’s fault, it was the composer’s. Julia’s vocal lines being absolutely the most important element of the sequences, and given the traditional limitations and challenges of writing for off-stage voices, Tchaikovsky’s rich orchestration and vocal writing probably should have taken that more into consideration.

A modern solution for future productions, (of which I hope there will be many—my English translation gratis), would be to forget the back-stage and off-stage voice placement and send their sound through speakers from the ceiling of the house, even sending the separate vocal lines down from either side, antiphonally if you will. The audience should ideally hear surreal voices coming from heaven—and understand the words.

On that note, let me strongly advocate for performing operas in translation. Operatic puritans’ desire to preserve the musical sound of a composer’s work is admirable, but by opposing performances in translation, they often discount the verbal sound and deny “foreign” audiences a full appreciation of the drama in a work, especially so in this one. As a Russian scholar, I observe that with its intensely poetic language (i.e., twisted word order and obscure, stylized vocabulary—not to mention some wild musical calisthenics on important words), Tchaikovsky’s Russian libretto for “Joan of Arc” verges on the unintelligible even for native speakers of that language. In some respects, the composer seems to have chosen to rely on the visual scenes (Pictures) to suggest most of the theater in his work and considered the verbal fine points of the drama as more or less negligible.

Yet, Joan’s drama is the truly grand part of this grand opera. Like the angel voices, audiences deserve to comprehend fully her inspiration, heroism, moral anguish, triumph, and apotheosis. Her story is of vast import even for today: a woman of incredible strength and determination who literally saved her country, a powerful spirit who transcended medieval superstition and ignorance to achieve Sainthood—her true moral victory. All the more astounding for happening six centuries ago, Joan’s victory needs not be reduced to mere musical fireworks and orchestral magnificence. To convey all the grandeur, her glorious words should be readily comprehensible.

That’s why I’ve devoted creative energy to this amazing work for more than forty years. And that’s why I now urge opera companies in English-speaking countries everywhere to produce it—now readily available in translation—and to thrill us with the brilliance of Joan’s glory, as so beautifully done by the New Orleans Opera Association.

#

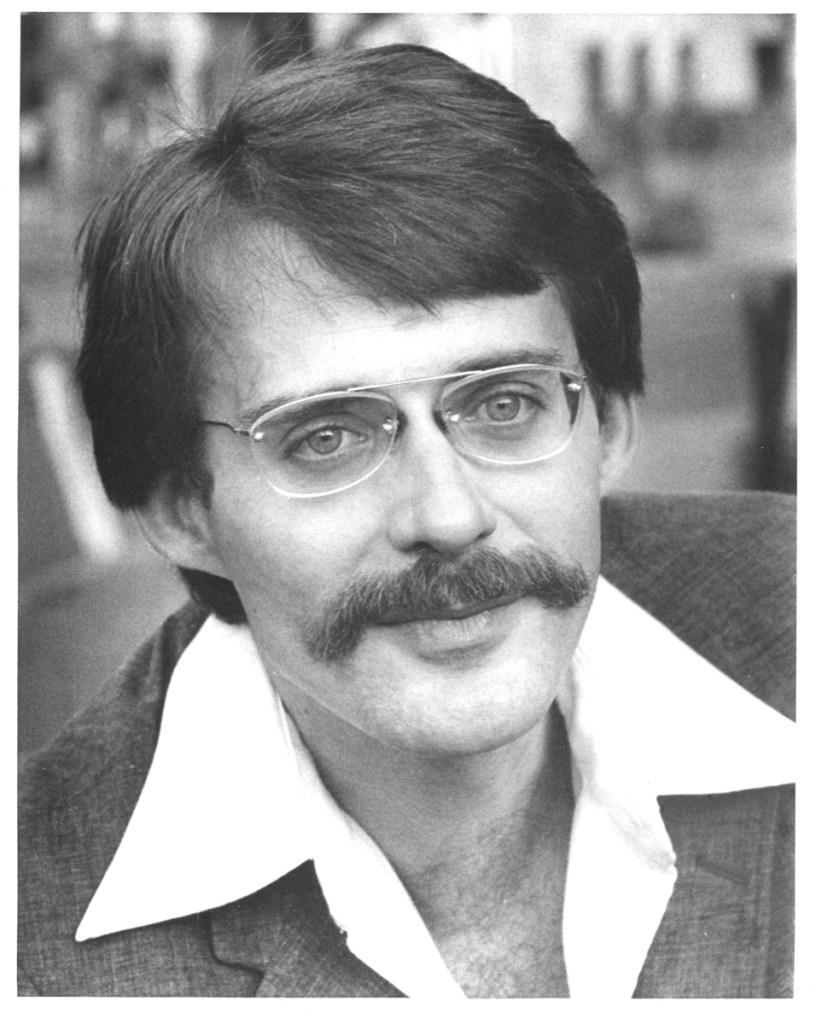

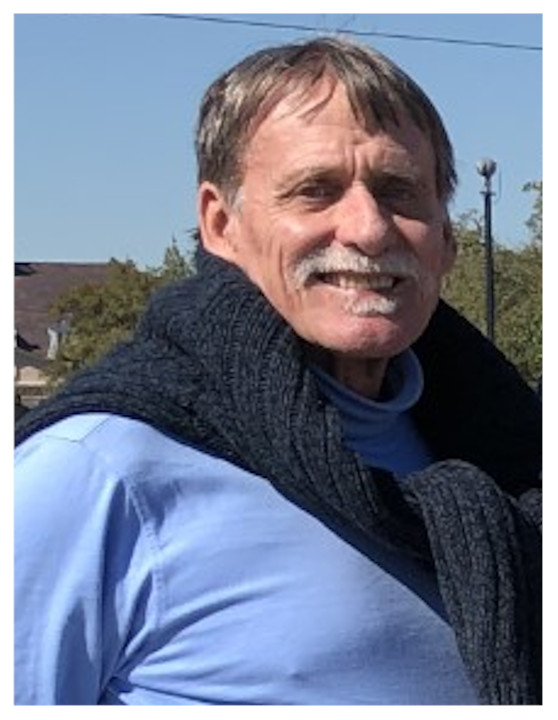

Richard Balthazar is a former Russian scholar, arts administrator, and vendor of used plants, now happily retired as a writer and artist. He can be reached at rbalthazar@msn.com.