—Not to care is divine. So I screwed up way back there in January, 2019 on Icon #16 which I titled TECCIZTECATL & METZTLI, Deities of the Moon. Operating on what I’d learned thirty years earlier for my book of days, I based my totally fanciful drawing of Tecciztecatl being the Nahua people’s male lunar deity ruling their sacred calendar’s 13-day week (trecena) One Death. I read that they stuck him into the calendar to replace the ancestral female lunar deity Metztli.

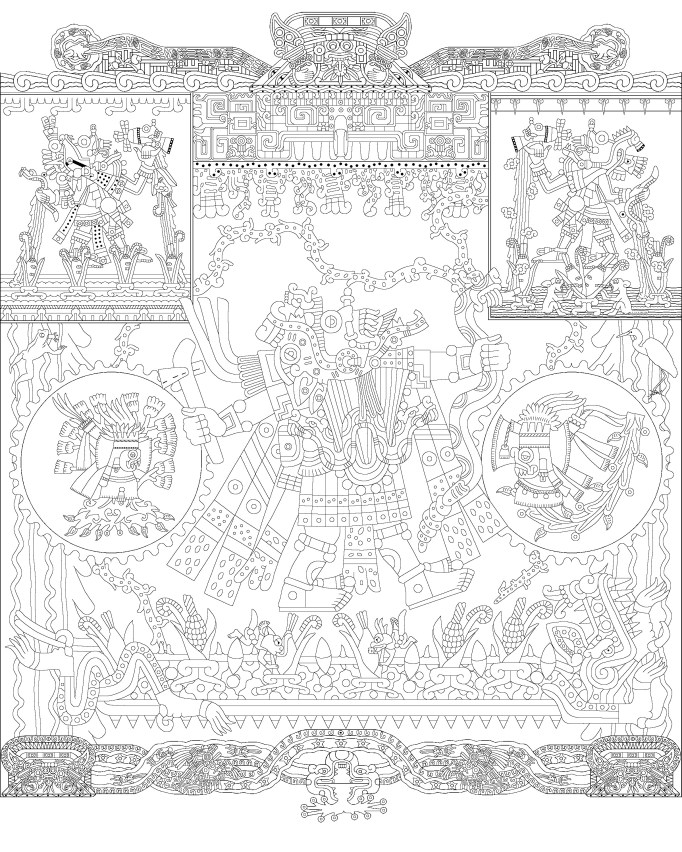

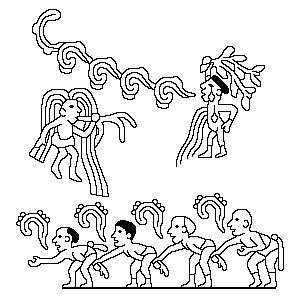

I could only imagine him then through the lens of Codex Nuttall, the only codex I’d seen in detail that long ago before the internet. Using Nuttall motifs, I constructed a standard half-kneeling figure with stylistically consistent regalia, but I had no idea even that thing in his right hand was an incense bag. I felt quite proud of my trick of turning his face into a moon, also blissfully unaware that the Aztecs saw a rabbit in it instead. We live and learn.

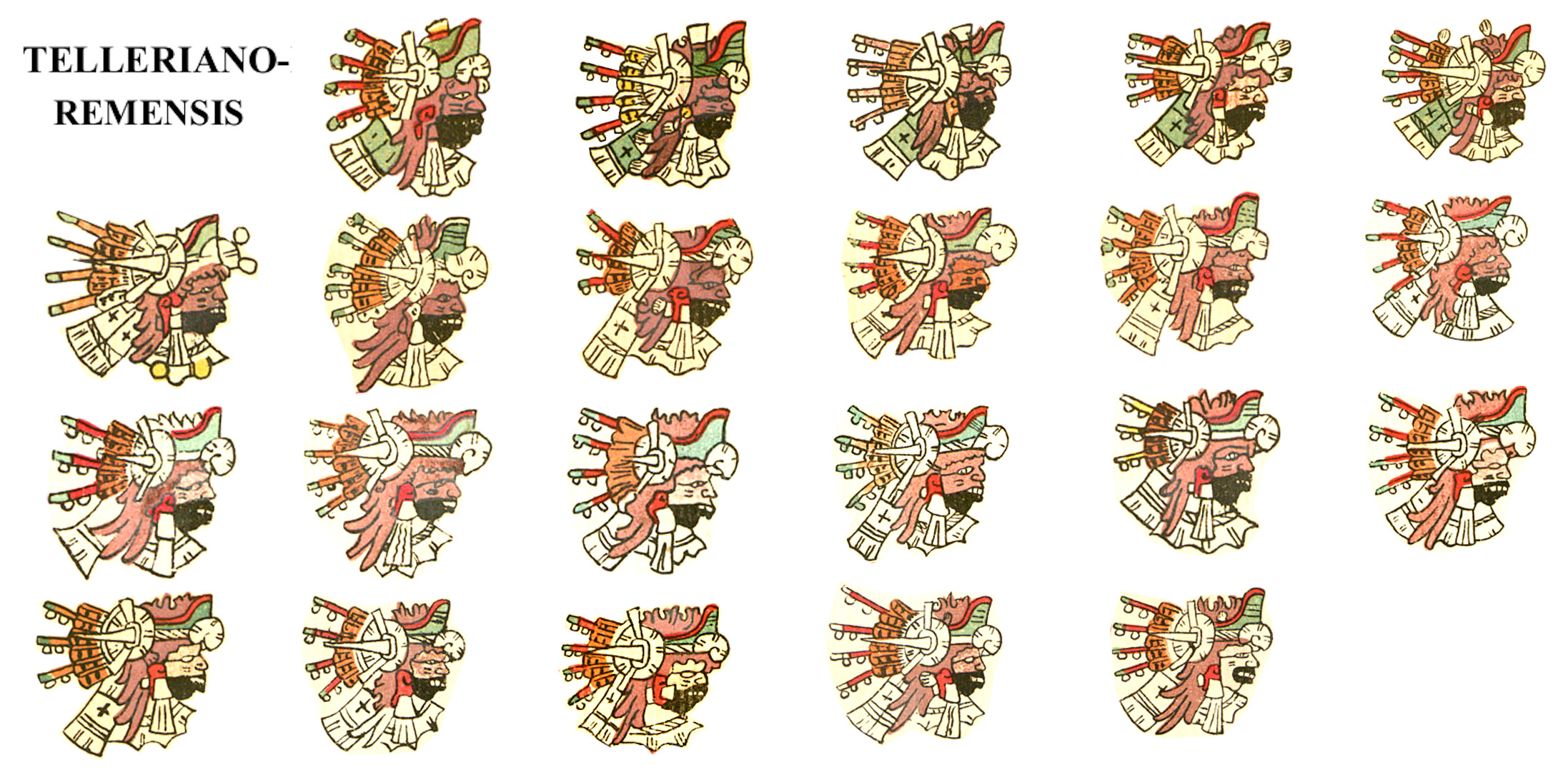

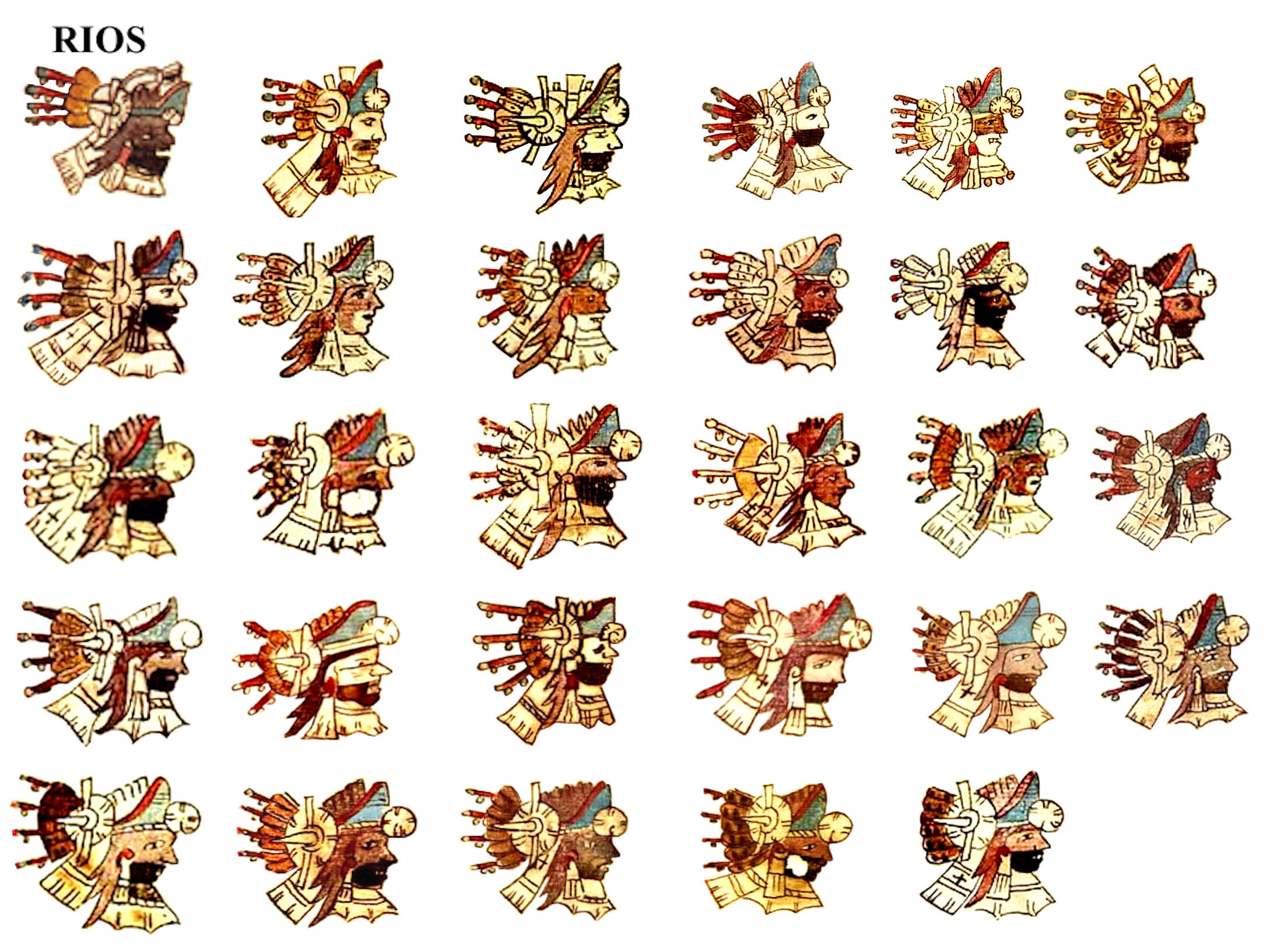

For Icon #16 in late 2018 when I still wasn’t very well-versed in my digital collection of Aztec codices, I chose for models the images in Codex Telleriano-Remensis and its later Italian copy Codex Rios (T-R/R). It looked to me like they’d placed both male and female deities together for that week. I didn’t even wonder about that sun-thing on his back.

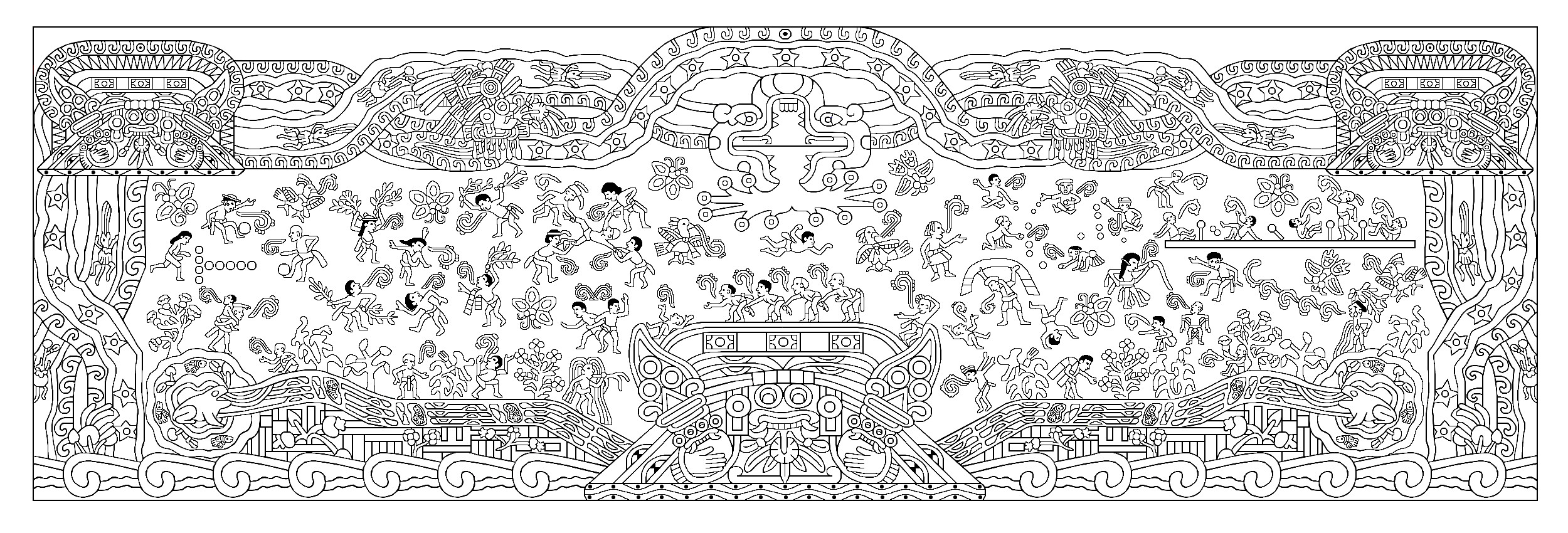

Only recently learning about the books of days in the other codices, I’ve discovered a different situation. Tecciztecatl is indeed shown as one of the patrons of the week One Death, but he only accompanies Metztli (who’s much smaller), in the Tonalamatl Aubin. In all of them, the god of the moon looks a lot different.

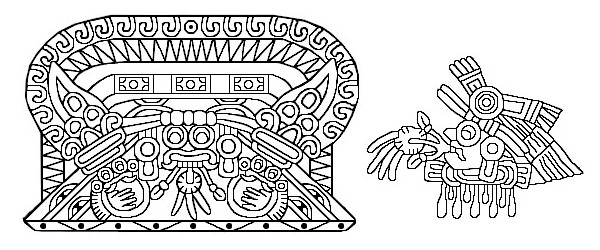

In the others, the moon god is in company with the big guy, Tonatiuh, god of the Fifth Sun (the present era), and clearly that’s who rules here in T-R/R with the old goddess. Look at that sun-thing on his back, and the bird was yet another dead giveaway. (By the way, I believe the ancient Maya goddess of the moon Ix Chel was AKA the Old Goddess.)

It’s interesting how this week is ruled by both the sun and the moon. Only in Codex Borbonicus, Borgia, and Vaticanus was Tecciztecatl inserted in Metztli’s place with Tonatiuh. Does that mean these three examples were maybe more central in Nahua culture? What can we say about his appearance with Metztli in place of Tonatiuh in Aubin? Obvious doctrinal differences…

Frankly, it seems to me that my models in T-R/R are relics of the ancient Mesoamerican calendar before Tecciztecatl usurped the week One Death in cult traditions. That begs the question of when Tonatiuh himself was installed in it as a patron beside the moon. After all, he wasn’t around during the Fourth Sun, and we can reasonably assume that this sacred Count of Days (tonalpohualli), was running even then—maybe with Metztli in total charge of One Death?

In any case, also being a divinity. I don’t care about my mistake. With this confession, perhaps I’ve atoned for it, and I’ll make appropriate edits elsewhere. But I find it rather fascinating that my silly mistake didn’t really damage Icon #16’s authenticity, just its title, which should now be TONATIUH & METZTLI, Deities of the Sun and Moon.

In fact it was the young god Nanahuatzin who threw himself first into the cosmic conflagration to become Tonatiuh, the Fifth Sun, and timid Tecciztecatl simply dawdled—becoming the moon instead. So that little figure immolating himself is now Nanahuatzin, which makes no difference to the icon’s integrity. I love mistakes that correct themselves.

This excursion in esoterica makes me wonder if my next Aztec icon for the coloring book YE GODS! really should be for Tonatiuh after all. I seem to have had him now, and Tecciztecatl feels distinctly second hand. This could be my excuse to take up with the fascinating and dangerous Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli, the Lord of the House of Dawn. Wish us well…

#