It’s been about nine months since the last addition to my coloring book YE GODS! Icons of Aztec Deities, #15, Quiahuitl, God of Rain. After completing it back last April, I had to focus on setting up the two-month Ye Gods! exhibition in Santa Fe, as well as prepare and deliver several lectures. Then everything else, including work on my second memoir, had to be put on hold while I concentrated for three months on re-translating an opera from Russian (which will be produced by the New Orleans Opera in February, 2020). Meanwhile I also set up the exhibition for another month in nearby Española. Busy boy, no?

Finally by late November, I got back to drawing, and now I’m thrilled to announce that #16 is finished at last. (At first I thought it was Tecciztecatl and Metztli, Deities of the Moon, but much later I’ve now discovered that it is Tonatiuh and Metztli, Deities of the Sun and Moon.)

TONATIUH & METZTLI

At first I worte that Tecciztecatl {tek-seez-te-katł}, the son of Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue, is a god of hunters and appears as things shining in the night. In the Nahua cosmology, when Quetzalcoatl and Ehecatl created the current Fifth Sun, Tecciztecatl wanted to become the new sun, but he hesitated to jump into the sacred fire, whereupon the young god Nanahuatzin leapt into the flames to become Tonatiuh, the Fifth Sun. When Tecciztecatl followed, he took second place as the moon. Well, it turns out that the little guy throwing himself into the fire here is actually Nanahuatzin, and the male deity here is Tonatiuh, the sun, in the pair with the moon.

Metztli {mets-tłee} is the ancestral moon goddess probably inherited from ancient Teotihuacan and/or the Maya’s lunar goddess Ix Chel. Long after the Nahuas demoted Metztli to merely being the consort of Tecciztecatl (in Tonalamatl Aubin), and replaced her with Tecciztecatl in several other codices, the later Aztecs tried to replace her completely with (the severed head of) Coyolxauhqui, the sister dismembered by their supreme god Huitzilopochtli.

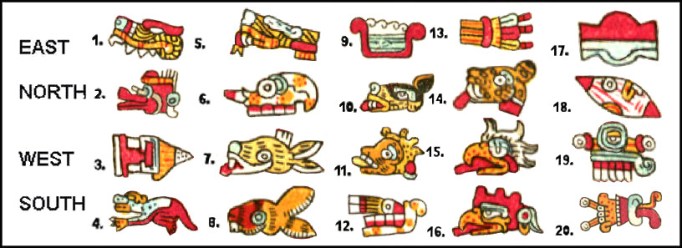

Tecciztecatl was stuck into the sacred calendar (tonalpohualli) as one of the patrons, frequently in the company of Tonatiuh, of the thirteen-day week One Death, which is shown in the encircling day-signs. It should be noted that there are thirteen days between the full and dark of the moon. The Mesoamerican cultures saw a rabbit in the full moon (top), and the serpent of the night devouring the rabbit (bottom) represents the dark of the moon. Incidentally, the nocturnal jaguar was closely connected with the moon, and the conch shell was the standard symbol of the moon.

I fired the drawing off to my dear friend Sagar in Bangladesh for him to work his vectorizing magic on it, and he did the trick. I’m currently (in January) posting the jpeg version with caption and sources on the coloring book page and have now (in April) have added the vectorized versions to the list of various sizes available for free download.

In my strict alphabetical sequence, the next deity to tackle is Tepeyollotl, Heart of the Mountain, who has several dramatic aspects. You can check out my earlier image of this god among the Aztec images from the old book on the calendar. If the creek don’t rise, I’d like to get his icon done by April. Once again meanwhile, in my multi-tasking fashion, I’ll be arranging more venues for the expanded exhibition and lectures—and forging onward in my memoir. Call me driven, but I’d love to finish that by next year.