The twentieth and final trecena (13-day “week”) of the Aztec Tonalpohualli (ceremonial count of days) is called Rabbit for its first numbered day, which is the 8th day of the veintena (20-day “month”). In Nahuatl, Rabbit is Tochtli. It was known as Lamat (Venus, Star) in Yucatec Maya, and K’anil (or Q’anil) (Seed of Life) in Quiché Maya.

The day Rabbit signifies self-sacrifice and service to something greater than oneself. Counter-intuitively, Rabbits were seen as gods of drunkenness, the Centzon Totochtin (400 rabbits) being patrons of all kinds of intoxication or inebriation. The principle rabbit deity was 2 Rabbit (Ome Tochtli or Tepoztecatl). The Aztecs counted “rabbits” for intoxication levels, from 25 rabbits for mild intoxication to 400 rabbits for complete drunkenness. Vessels for the drinking alcoholic pulque often bear rabbit symbolism and/or a crescent moon symbol called the yacametztli—relating to the goddess of the moon Metztli. In fact, Mesoamerican cultures envisioned the figure of a rabbit in the moon, which I’ve surmised was day-named 12 Rabbit.

The patron of the day Rabbit is Mayauel, the goddess of intoxication/pulque and its source, the maguey plant. Seen previously as patron of the Grass Trecena, she’s the purported mother of the Centzon Totochtin, apparently by the deity Patecatl, god of medicine and pharmaceutical intoxication. Other sources suggest that the Cloud Serpent, Mixcoatl, sired some of them, but Aztec paternity wasn’t thoroughly documented, and Mayauel was a hospitable goddess.

PATRON DEITIES RULING THE RABBIT TRECENA

One of the patrons of the Rabbit trecena is Xiuhtecuhtli (Lord of Fire and Time), whom we’ve seen in the Snake trecena. As god of the Center and the Pole Star, he’s an A-list celebrity deity. The other is variously Itztapaltotec, Stone Slab Lord, or Xipe Totec, Lord of Renewal and Liberation. The first is a nagual (manifestation) of the second and deifies the sacrificial knife.

AUGURIES OF THE RABBIT TRECENA

By Marguerite Paquin, author of “Manual for the Soul: A Guide to the Energies of Life: How Sacred Mesoamerican Calendrics Reveal Patterns of Destiny”

https://whitepuppress.ca/manual-for-the-soul/

Theme: Leadership and Renewal. During this final trecena in the 260-day cycle, the emphasis is on completion and “cutting away” what is no longer needed, in order to facilitate new growth. This can be an intense period, as combat in some areas could intensify, leading to important conclusions, as the stage is being set for new beginnings to follow in the next trecena. During this period signs or signals may appear that could indicate what lies ahead or new potentialities. This is a good time to watch for signs of change and growth, and a good time to make important decisions in preparation for the new cycle about to begin.

Further to how these energies connect with world events, see the Maya Count of Days Horoscope blog at whitepuppress.ca/horoscope/ Look for the Lamat trecena.

THE 13 NUMBERED DAYS IN THE RABBIT TRECENA

The Aztec Tonalpohualli, like the ancestral Maya calendar, is counted through the sequence of 20 named days of the agricultural “month” (veintena), of which there are 18 in the solar year. Starting with 1 Rabbit, it continues with: 2 Water, 3 Dog, 4 Monkey, 5 Grass, 6 Reed, 7 Jaguar, 8 Eagle, 9 Vulture, 10 Earthquake, 11 Flint, 12 Rain, and ultimately 13 Flower.

There are a few special days in the Rabbit trecena:

One Rabbit (in Nahuatl Ce Tochtli) – a date in the mythic Aztec past when the cosmos was created by gods; also, one of Xiuhtecuhtli’s calendric names.

Five Grass (in Nahuatl Macuil Malinalli) – one of the five male Ahuiateteo/Macuiltonaleque (Lords of the Number 5), usually paired with the female Cihuateotl One Eagle.

Thirteen Flower (in Nahuatl Mahtlactli ihuan yeyi) – a ritually significant day of completion for the 260-day cycle; also associated with period endings, often marking the completion of significant “bundles” of time.

THE TONALAMATL (BOOK OF DAYS)

Several of the surviving so-called Aztec codices (some originating from other cultures like the Mixtec) have Tonalamatl sections laying out the trecenas of the Tonalpohualli on separate pages. In Codex Borbonicus and Tonalamatl Aubin, the first two pages are missing; Codex Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Rios are each lacking various pages (fortunately not the same ones); and in Codex Borgia and Codex Vaticanus all 20 pages are extant. (The Tonalpohualli is also presented in a spread-sheet fashion in Codex Borgia, Codex Vaticanus, and Codex Cospi, but that format apparently serves other purposes.)

TONALAMATL BALTHAZAR

As described in my earlier blog The Aztec Calendar – My Obsession, some thirty-five years ago—on the basis of very limited ethnographic information and iconographic models —I created my own version of a Tonalamatl, publishing it in 1993 as Celebrate Native America!

When I started drawing my tonalamatl, I did the pages in colored pencil, often producing several versions in different color schemes in a palette of four chromatic colors (with some black and white as well): gold—for gods, red—for blood, green—for jade, and blue for turquoise. Each deity had a primary color with a secondary and highlights of the others. For the last trecena, I used models and motifs from Codex Nutall and tried to make it an even balance of all four colors. Maybe I succeeded because everyone admired this image especially.

On the first nineteen trecenas, I followed the limited information available about their patrons (not knowing all of them). Many I created from scratch from Nutall images and sketchy clues on iconography. A few were based on images from Codex Borbonicus found in old books. When I got to the last one, Rabbit, the scholarship said only that its patron was the sacrificial knife, and I found only one gruesome image, probably the monster from Tonalamatl Aubin. (See below.) As an artist, I was aesthetically and philosophically offended and decided to turn heretic.

I installed my own choice of a god as patron of the last trecena, someone considerably more appetizing. Xochipilli, the Flower Prince, is god of art, dance, beauty, ecstasy, sleep, and dreams/hallucinations. In addition, he’s variously patron of homosexuals and male prostitutes; god of fertility (agricultural produce and gardens); patron of writing, painting, and song; and god of games (including the sacred ball-game tlachtli), feasting, and frivolity. His twin sister/wife is Xochiquetzal, patron of the preceding Eagle trecena.

So much for authenticity. The neglected Flower Prince is an eminently worthy “calendar prince.” (You can see the true trecena patrons in the tonalamatls of the historical codices that follow.)

#

TONALAMATL BORGIA (re-created by Richard Balthazar from Codex Borgia)

The page for the Rabbit trecena from Codex Borgia, which I hadn’t seen thirty-five years ago, portrays its orthodox patrons in typically ornate style. Xiuhtecuhtli on the left is loaded down with divine regalia, some of it the same as in his image with the Snake trecena, and in similar coloration. The only truly emblematic piece is his square pectoral, apparently a heavily stylized war-butterfly motif inherited from the ancient Maya. I find his headdress curious in reflecting that of Ixtlilton in the preceding Eagle trecena. Maybe the artist enjoyed drawing those motifs.

On the right side, we have one of the more spectacular images of Xipe Totec illustrating his traditional red and white ornaments and staff. It’s in a much different style than his image as patron of the Dog trecena, sharing only the unique nose-clamp. In this Borgia portrait, he’s definitely the “flayed god,” like a priest in the skin of a sacrificial victim.

If I’d known about this panel, I might have avoided heresy by making Xipe Totec the patron of my Rabbit trecena, but I’d already used him for Dog and wouldn’t have wanted to repeat patrons anyway. The same argument holds for Xiuhtecuhtli already having appeared in Snake. In any case, while perhaps not as eye-catching as Chalchiuhtotolin in the Water trecena, Borgia’s two lords for the final Rabbit trecena are about as stylistically exquisite as its deities get.

#

TONALAMATL YOAL (compiled and re-created by Richard Balthazar on the basis of

Codex Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Rios)

Here we see on the left the ominously named Itztapaltotec, Stone Slab Lord, himself, the sacrificial knife that grossed me out. This one looks like a guy in a flint knife (tecpatl) costume with flayed arms hanging from his own like an appropriately nagual hybrid of Xipe Totec. He holds an emblematic red and white staff, but I can’t fathom the conch shell in his other left hand.

On the right side sits Xiuhtecuhtli more or less enthroned, which is the first remarkable detail. Almost all the Yoal deities are either standing (like Itztapaltotec) or in what I call the “dancing” pose with bent knees. Only the Cihuateotl in the Flower trecena and Xochiquetzal in the Eagle trecena sit back on their feet, standard female posture, (especially in Codex Nutall where males sit cross-legged.) Adding to this iconographic weirdness, note that Xiuhtecuhtli’s right leg and foot are hidden by the left—an absolutely ideoplastic device.

Above and beyond that odd detail, the Lord of Fire is decked out in opulent finery. Check out that wild serpent/crocodile head by his ear, possibly a plug ornament. His extravagant array of Quetzal plumes splays more feathers than even Xochiquetzal in the Eagle trecena, and between him and Stone Slab they wear more than in any other Yoal patron panel. The artist may have overdone the plumage because in his tailpiece and bustle the feathers had to overlap—a definite problem for Aztec iconography. One of the plumes in the back-fan even droops behind another!

Passing by his war-butterfly pendant, we see in his lower right hand what looks surreally like a rattlesnake with an animal head. It’s in fact a ritual “shaman stick.” More usually it’s called a “deer stick,” though many don’t look at all like a deer’s head. Plain ones were often used for digging, but the rattles on this one were probably there to make magical noises.

In the original, the scepter in the god’s other right hand was terribly drawn and unrecognizable, and I substituted the finer Xiuhcoatl (fire-serpent) he holds in the Snake trecena. The strange position of his fingers—as though holding on to a ring—is an exact duplication of that detail in his Borgia icon. There I simply wondered about it, but seeing it again here, I begin to suspect that there’s some symbolic importance attached to it. I guess we’ll never know.

Moving on to the divine face, I confess to doing radical plastic surgery on the original which looked insanely like the cartoon character Homer Simpson. That simply wouldn’t do! Then I borrowed the face-painting pattern again from his image in Snake. The result was a respectable deity worthy of his portentous headdress (like that worn by him and Mictlantecuhtli in the upper row as lords of the night). According to Gordon Whittaker in “Deciphering Aztec Hieroglyphs,” that turquoise diadem with curved point in front is literally a hieroglyph for “Lord” or “ruler.” Whittaker adds that the Nahuatl word is teykw-tli pronounced in two syllables if you can wrap your tongue around that. Colloquially, that’s te-cuh-tli, as in Xiuhtecuhtli (fire/turquoise-lord).

As with Tonalamatl Borgia, Tonalamatl Yoal went all out on the patrons of the Rabbit trecena, lavishing them with divine detail. The tonalamatl presents many elegant figures, but in my opinion, only the panel for the Vulture trecena (Evening Star and Setting Sun) can compare to this ornate, many-plumed pair. The inspirations behind the Yoal trecena pages are superbly artistic visions of glorious mythological beings.

The twenty striking patron pairs in the Yoal tonalamatl encapsulate the traditional iconography of those Aztec deities. Having worked closely with the original codex images to re-create their conceptual inspirations, I can say that the later images in the series became progressively more awkward and crude, their construction often downright ramshackle. This suggests to me that other artists may have taken over some panels—or maybe the artist simply slacked off in his work—or equally probable, the artist got drunk or stoned.

In my careful estimation however, the Yoal artist(s)’s concept and vision of the trecena patrons were nevertheless sublime. Sadly, they just lacked the means, skill, medium, and (possibly) the reverence needed to manifest their deities magnificently. I’m thrilled to have turned those flawed visions into the Tonalamatl Yoal, a new treasure in the canon of Aztec art.

#

OTHER TONALAMATLS

The only thing that identifies Xiuhtecuhtli in the Tonalamatl Aubin patron panel is his black face-paint. The generic circular pendant could belong to many deities. On the other hand, the figure on the left is clearly Itztapaltotec, a frighteningly personified sacrificial knife with a surreal face on his shoulder. The item at top center is a hearth-vessel with smoke, fire and possibly incense, but I won’t attempt to identify the other elements.

This patron panel and that for the Water trecena (with Chalchiuhtotolin) are the two most disappointing instances in the Tonalamatl Aubin. Most of the other panels are passingly ornate, while often awkward and distorted. In my humble opinion, this tonalamatl is the least impressive of the several we have seen. It was painted pre-Conquest in the neighboring state of Tlaxcala and as such may represent a crude, provincial document. Its value for scholarship is that it represents the shared themes and motifs across the “religious” territory of central Mexico.

#

The panel for this last trecena in Codex Borbonicus is artfully done, supplying the figure of Xiuhtecuhtli that I used as a model in the earlier Snake Trecena in my old tonalamatl. Oddly, I don’t believe I saw this decorative image of Itztapaltotec way back then. I was so taken my Xochipilli apostasy that I probably would’ve ignored the fancy fellow anyway. Though some of the surviving panels in Borbonicus present stunning figures (like Itztlacoliuhqui in the Lizard Trecena), this beautiful pairing of patrons has to be the most impactful composition of the lot.

The patrons’ emblematic paraphernalia is easily recognizable, as are many of the items in the neatly organized conglom. I’m intrigued by the bottom center item resembling a hill or mountain place-symbol with tooth-like appendages (which Whittaker has identified as hieroglyphs meaning “at”) and part of its vegetative detail in utter disarray. Most notable is the curved “deer-stick” hovering over Itztapaltotec’s flint knife, simpler than that in the Yoal panel, but scarcely more deer-like. This one is probably a common digging stick but might still be magical.

Combining these patron panels with a crowded matrix of delicately drawn days, 9 night-lords, and 13 day-lords with their totem-birds, the tonalamatl in Codex Borbonicus stands in my modest opinion as a consummate masterpiece of Aztec art and culture.

#

In Codex Vaticanus, the patron pair for the Rabbit Trecena again is well balanced, as in the other tonalamatls, to formally wrap up the last of the trecenas. In its characteristic rough caricature style, Vaticanus again closely follows the images and themes of Tonalamatl Borgia, Xipe Totec and Xiuhtecuhtli simply having switched sides. In its series of trecena panels, Vaticanus faithfully reflects the calendrical “dogma” in the more ornamental Borgia panels. The codices share certain other sections, but each also presents a lot of its own mythological material. Perhaps the calendrical orthodoxy can be explained by both codices having come from Puebla, possibly from the same priestly school (calmecac).

But the tonalamatl in Codex Vaticanus does more than simply restate the Borgia images. In particular, it created that uniquely surreal vision of Itzpapalotl for the House Trecena and produced its own exquisite versions of deities like Chalchiuhtotolin and Xolotl for the Water and Vulture trecenas. In addition, in its other sections, Vaticanus presents incomparably elegant artwork on deities like Tlaloc and Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli. The codex is a veritable goldmine of mythological and ethnological details. One just has to get used to its stylistic strangeness, like the blue finger- and toe-nails.

#

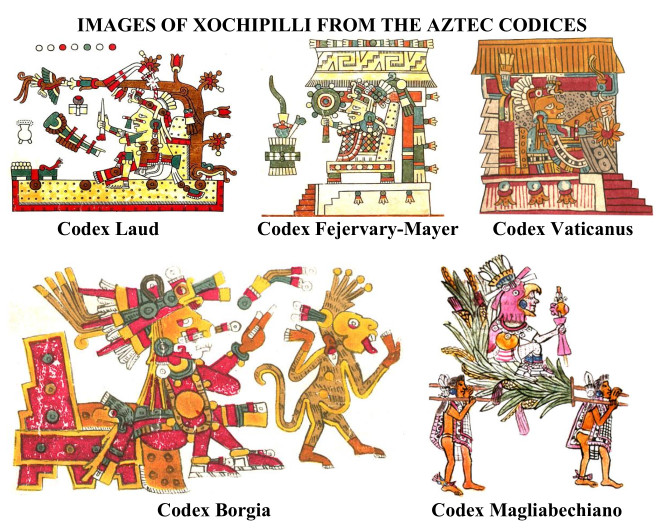

Tonalamatl Borgia is my proudest achievement in this series of re-created Aztec art. Like the Vaticanus version of the trecenas, it’s set amongst several other ritual and religious sections of the codex, many of stupendous artistry. Though several other historical codices are also iconographically superlative, like Fejervary-Mayer and Laud, to my mind, Codex Borgia is the premiere artistic relic of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica.

Unfortunately, over five centuries the document has seriously deteriorated with whole sections of images worn away, the colors of its inks fading and failing, and some pages torn or even burned. Mostly, what we can see nowadays of Codex Borgia (and many other codices) is from the incredible facsimile editions of Joseph Florimond Loubat (1837-1921), an American bibliophile. He faithfully reproduced the Aztec documents in their exact conditions at the end of the nineteenth century, which meant that any earlier deterioration was also reproduced. In 1993 a full-color restoration of the Codex Borgia was published by Giselle Díaz & Alan Rodgers, restoring most dilapidated areas and repairing lost coloration in facsimile fashion.

My re-creations of Tonalamatl Borgia have played somewhat more freely with its colors. I’ve interpreted various shades of greys, browns, and golds in the Loubat facsimiles as deteriorated original blues and greens and in a few instances introduced colors not available to the Aztec artists (like the purples with Chalchiuhtotolin in the Water Trecena). My purpose was to present the deities in authentic but new, vibrant images untouched by the passing centuries.

A curious feature of the Tonalamatl Borgia is that some of its decorative patron panels seem to suggest an underlying narrative, in particular that for the Snake Trecena. Other panels include mysterious and beautiful symbolic items (though not as many as in Codex Borbonicus), and a number of the Borgia deities, like Chalchiuhtlicue in the Reed Trecena and Tlaloc in the Rain Trecena, are perfectly monumental. In summation, I believe that this Tonalamatl Borgia deserves a place of honor amongst the world’s very best religious art.

#

AFTERWORD

by Marguerite Paquin, PhD.

I would like to express my deepest thanks to Richard for his extremely valuable contributions to my Maya Count of Days Horoscope blog. This began in early December of 2019, when he allowed me to use his Tonalamatl Balthazar image for the Chikchan trecena as an illustration for the blog. (https://whitepuppress.ca/the-chikchan-lifeforce-trecena-dec-10-22-2019/) The evolution of imagery continued from there as he developed and refined his work.

After the inclusion of one full cycle of his Tonalamatl Balthazar, I began including his early renditions of the Codex Borgia in the blog. At first the images were somewhat sketchy (but valuable nonetheless) but over the years he kept refining them, and the full set is now gorgeously complete. I am blessed to have them available for my blog, as they allow my readers to see at a glance the nature of the energies that I discuss every 13 days.

When Richard began adding descriptions of his work (regarding the evolution of the images, and the detailing that was included) in his own site, this added yet another layer of interest. I am extremely appreciative of Richard’s talent, research, formidable attention to detail, and generosity in this regard, and have no doubt that the ancients who devised these images in the first place would be proud. Muchas gracias, Richard!

###

You can view all the calendar pages from the Balthazar, Borgia, and Yoal Tonalamatls

in the Tonalamatl gallery.