The eighth trecena (13-day “week”) of the Aztec Tonalpohualli (ceremonial count of days) is called Grass for its first numbered day, which is also the 12th day of the veintena (20-day “month”). In the Nahuatl language Grass is Malinalli, and it’s known as Eb’ in Yucatec Maya and E or Ey in Quiché Maya.

According to references I found long ago, for the Aztecs the day Grass signified penance and self-flagellation as an offering to the gods; though it may be no reflection on such suffering, the day Grass is anatomically connected to the bowels. The patron of the day Grass is Patecatl, the god of medicine (herbology), healing and fertility, and surgery. A pulque deity like his wife Mayauel, he’s the god of intoxication by hallucinogenic mushrooms, peyote, and psychotropic herbs such as datura (jimson weed), morning glory, and marijuana, as well as of plants used in healing, fortune telling, shamanic magic, and public religious ceremonies.

PATRON DEITIES RULING THE TRECENA

There’s unanimity that the principal patron of the Grass trecena is Mayauel (the aforementioned wife of Patecatl), a maternal and fertility goddess connected with nourishment who personifies the maguey plant, a member of the agave family. (See my Icon #9.) Besides fibers for ropes and cloth, the most important maguey product is the alcoholic beverage pulque (or octli). As a pulque goddess, Mayauel is the mother of the Centzon Totochtin (400 Rabbits), patrons of drunkenness by all forms of intoxication. (Drinking was generally only permitted in ceremonies, but the elderly were free to drink whenever they wished.) Her day-name is Eight Flint.

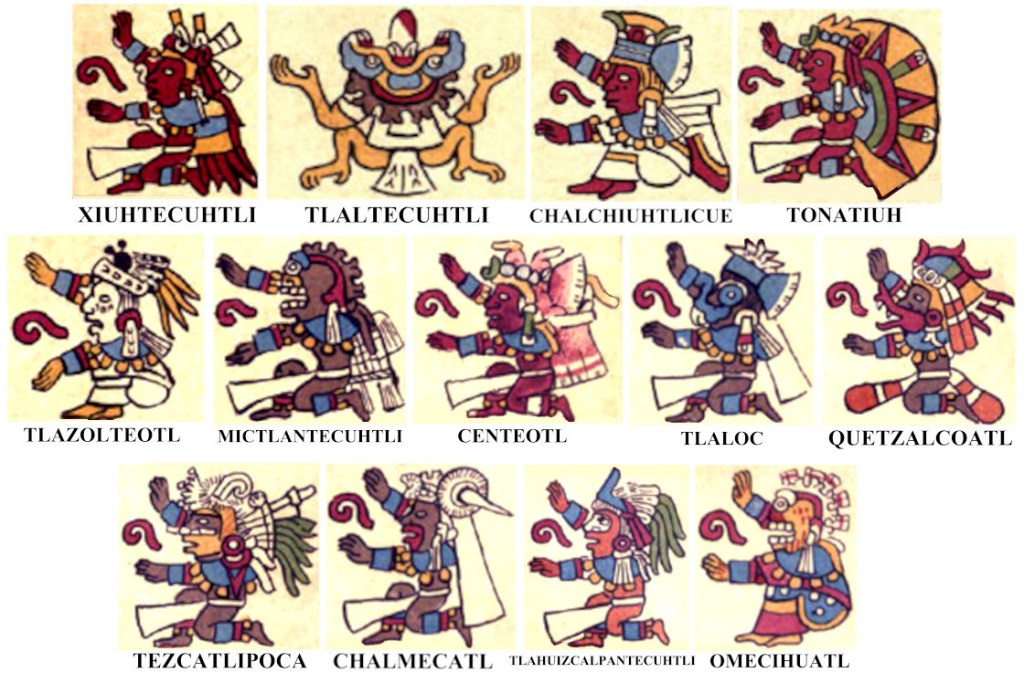

On the other hand, there’s considerable confusion about the secondary patron of this trecena. In most tonalamatls the male personage accompanying Mayauel bears no identifying emblems, but in the related Telleriano-Remensis and Rios codices (sources of Tonalamatl Yoal below), it’s unambiguously Centeotl, the god of maize, the 4th lord of the night and the 7th lord of the day.

AUGURIES OF GRASS TRECENA

By Marguerite Paquin, author of “Manual for the Soul: A Guide to the Energies of Life: How Sacred Mesoamerican Calendrics Reveal Patterns of Destiny”

https://whitepuppress.ca/manual-for-the-soul/

This trecena’s theme is vitality and fertility. Given that both patrons are oriented towards celebration, this period encompasses energies related to abundance and the promulgation of life. Many born during this time frame may easily tap into the generative and celebratory nature of these energies through feasting, dancing, and pleasure-seeking. Although both vision and empowerment are associated with these energies, caution might be needed to avoid issues created through excess, particularly during the intense final days of the trecena.

Further to how these energies connect with world events, see the Maya Count of Days Horoscope blog at whitepuppress.ca/horoscope/. The Maya equivalent is the Eb’ trecena.

THE 13 NUMBERED DAYS IN THE GRASS TRECENA

The Aztec Tonalpohualli, like the ancestral Maya calendar, is counted through the sequence of 20 named days of the agricultural “month” (veintena), of which there are 18 in the solar year. Starting with the 12th day of the current veintena, Grass, this trecena continues with 2 Reed, 3 Jaguar, 4 Eagle, 5 Vulture, 6 Earthquake, 7 Flint, 8 Rain, 9 Flower, 10 Crocodile, 11 Wind, 12 House, and 13 Lizard.

There are several important days in the Grass trecena:

One Grass (in Nahuatl Ce Malinalli) is the day-name of one of the tzitzimime (star demons), evil spirits who devour people during solar eclipses. The goddess Itzpapalotl is the principle tzitzimitl, as well as the patron of the Cihuateteo (as discussed earlier in the Deer trecena), which may indicate a relationship between these two categories of supernatural beings.

Two Reed (in Nahuatl Ome Acatl) is the day-name of the creator god Tezcatlipoca, though in his various manifestations other day-names are sometimes cited. As Ome Acatl (Omacatl), he was seen as patron of celebrations, often shown seated on a rush bundle symbolic of his role as the god of banquets. Two Reed was also one of the days when New Fire ceremonies are traditionally held (every 52 years).

Two Reed is also important for me personally as my day-name; I don’t pretend any relation to the god other than having a fondness for celebrations. In this personal context, the next day Three Jaguar (in Nahuatl Yeyi Ocelotl) is the day-name of my youngest grandson.

Five Vulture (in Nahuatl Macuil Cozcacuauhtli) is the day-name of one of the Ahuiateteo, the gods of pleasure and excess. Judging from the augury of the day Vulture, he’s the god of the joys of wealth and conversely of financial woes like poverty, (and oppressive responsibilities of great riches). Usually paired with the Cihuateotl One Eagle (Ce Cuauhtli), a goddess of bravery, Five Vulture is also one of the Macuitonaleque, patrons of calendar diviners.

Seven Flint (in Nahuatl Chicome Tecpatl) is the day-name of one of the several goddesses of tender young maize. (There are deities for all growth aspects of this staple crop.)

Ten Crocodile (in Nahuatl Mahtlactli Cipactli) is noted in the Florentine Codex as a day especially associated with wealth, happiness, and contentment.

THE TONALAMATL (BOOK OF DAYS)

Several of the surviving so-called Aztec codices (some originating from other cultures like the Mixtec) have Tonalamatl sections laying out the trecenas of the Tonalpohualli on separate pages. In Codex Borbonicus and Tonalamatl Aubin, the first two pages are missing; Codex Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Rios are each lacking various pages (fortunately not the same ones); and in Codex Borgia and Codex Vaticanus all 20 pages are extant. (The Tonalpohualli is also presented in a spread-sheet fashion in Codex Borgia, Codex Vaticanus, and Codex Cospi, but that format apparently serves other purposes.)

TONALAMATL BALTHAZAR

As described in my earlier blog The Aztec Calendar – My Obsession, some thirty years ago—on the basis of very limited ethnographic information and iconographic models —I presumed to create my own version of a Tonalamatl, publishing it in 1993 as Celebrate Native America!

My version of the Grass trecena featured a Nuttall-inspired image of the goddess Mayauel, and I showed her holding out a pot of pulque, a frequent motif in that codex. At the time I didn’t know about her personification of the maguey (or about any secondary patron) and resorted to the crocodile headdress and jaguar throne of one of the Nuttall ladies (Six Wind). I at least knew enough to include a cute little rabbit as a deity of drunkenness. If I might say so myself—and I will—the page achieves a rather iconic effect.

#

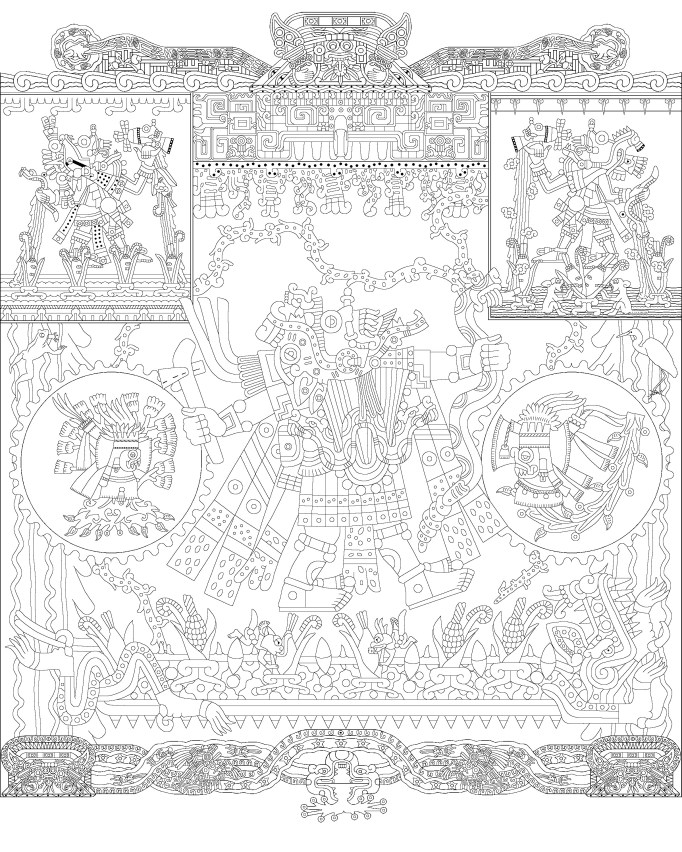

TONALAMATL BORGIA (re-created by Richard Balthazar from Codex Borgia)

The cultural importance of pulque is clearly indicated by the elegant, ornamented brew-pot in the center of the panel, almost overshadowing the trecena patron Mayauel on the right. She sports some intricate, unique regalia but is identifiable by the stylized maguey plant behind her. In that context, I prefer to think of these stylized realizations more as ‘surrealizations,’ not attempting a naturalistic representation but a universal image. More such ‘surrealized’ magueys will follow. So much for my half-baked artistic theory—which I would also apply to Aztec art in general.

I must confess to doing serious graphic surgery on the proportions of her legs, which in the original were so undersized that she looked like a hydrocephalic infant. Perhaps the Borgia artist’s aesthetic was impaired by drinking too much pulque? Also, I added standard wristbands to connect to the long tassels. Most curious is the blue on the lower half of her face.

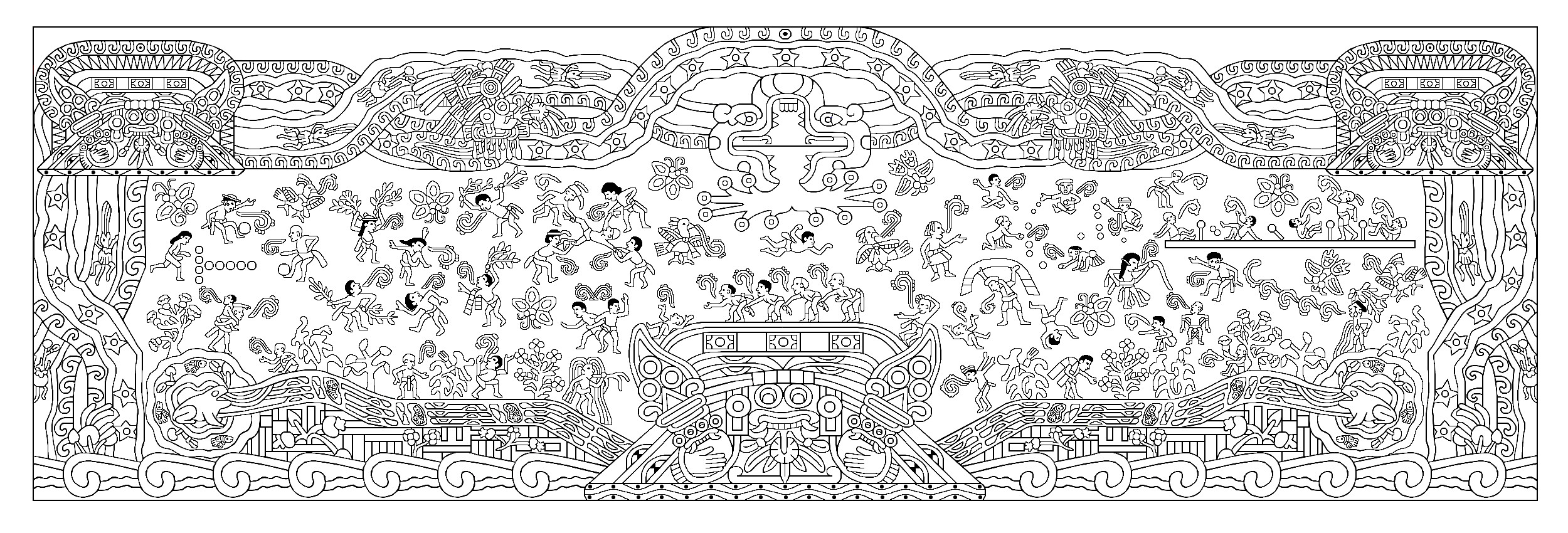

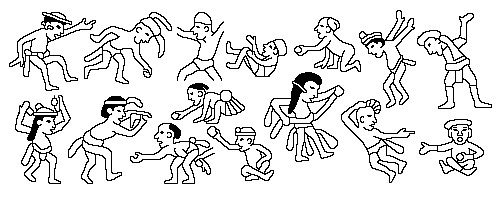

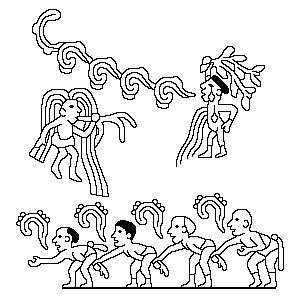

As noted earlier, the secondary patron on the left isn’t identifiable by anything in his regalia, though his throne and jaguar pelt show that he’s definitely a deity. I’m impressed by the dainty, naturalistic way he sips from his bowl of pulque. Other drinkers are usually more formally posed as in this pulque party in Codex Vindobonensis (from an incomplete facsimile):

This party was likely a formal/ceremonial affair involving important personages, some even masked, who were labelled with their day-names. One wonders about the two who stir their drinks with something (a celery stick?) and must note that the standard froth on their cups appears on the Borgia brew-pot but not on the unknown fellow’s cup.

One item in the background is of disturbing significance for divination: the heart on a stick. Does this imply that heart-sacrifice is part of the pulque ritual? I haven’t seen any scholarly mention of such—or maybe it’s a mysterious emblem of the drinker? If so, it’s no help at all in identifying this secondary patron of the trecena.

#

TONALAMATL YOAL (compiled and re-created by Richard Balthazar on the basis of

Codex Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Rios)

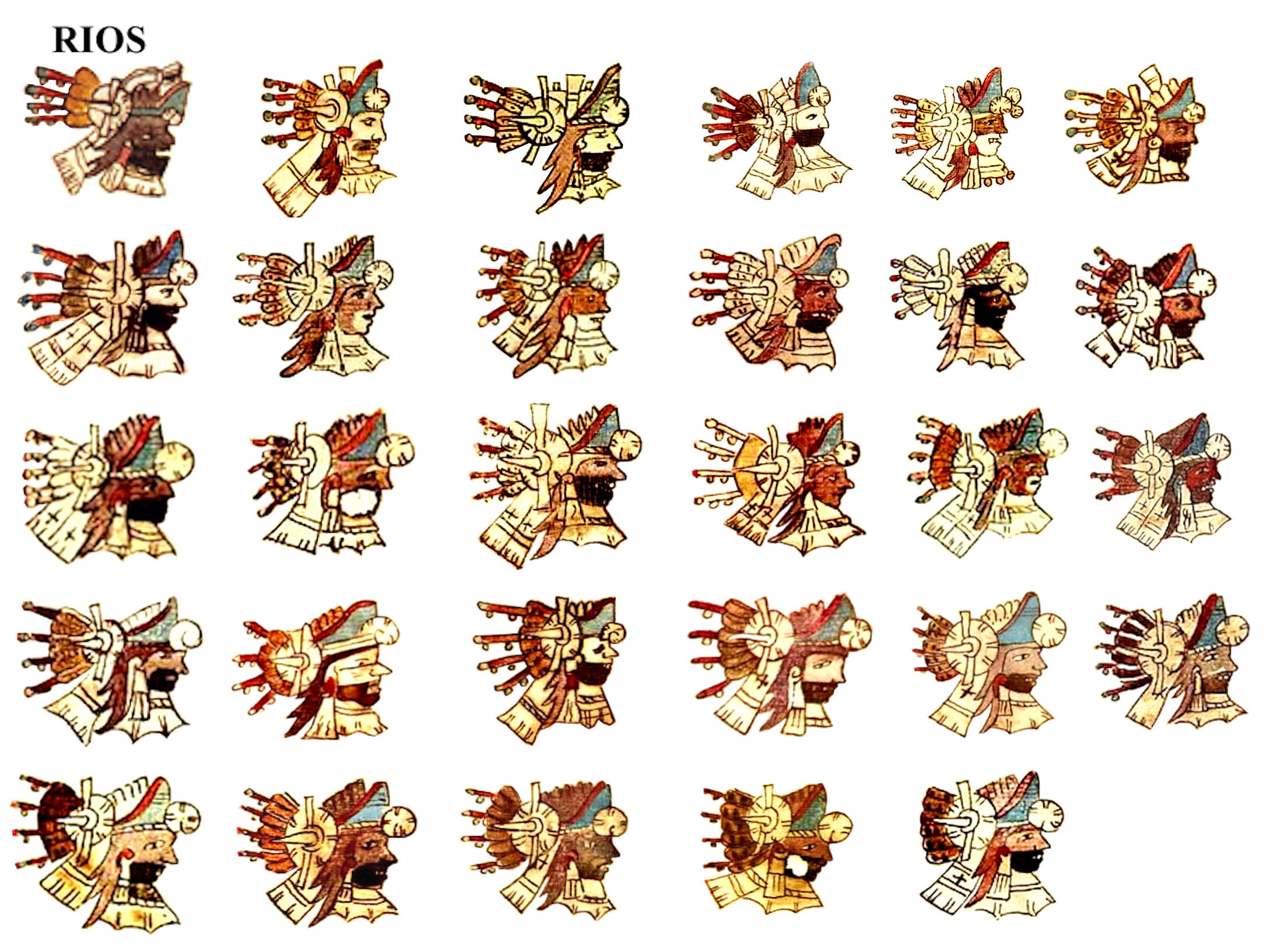

This image of Mayauel on the left is based on that from Codex Rios; her page in Telleriano-Remensis is missing. Here she rises up out of the maguey, which is ornamented by odd flowers and fruits. Again, she’s shown with a blue lower face, and speaking of ornaments, her over-sized headdress (also in blue and white as in Codex Borgia) is topped with three mushrooms indicating her interest in that means of entheogenic intoxication as well.

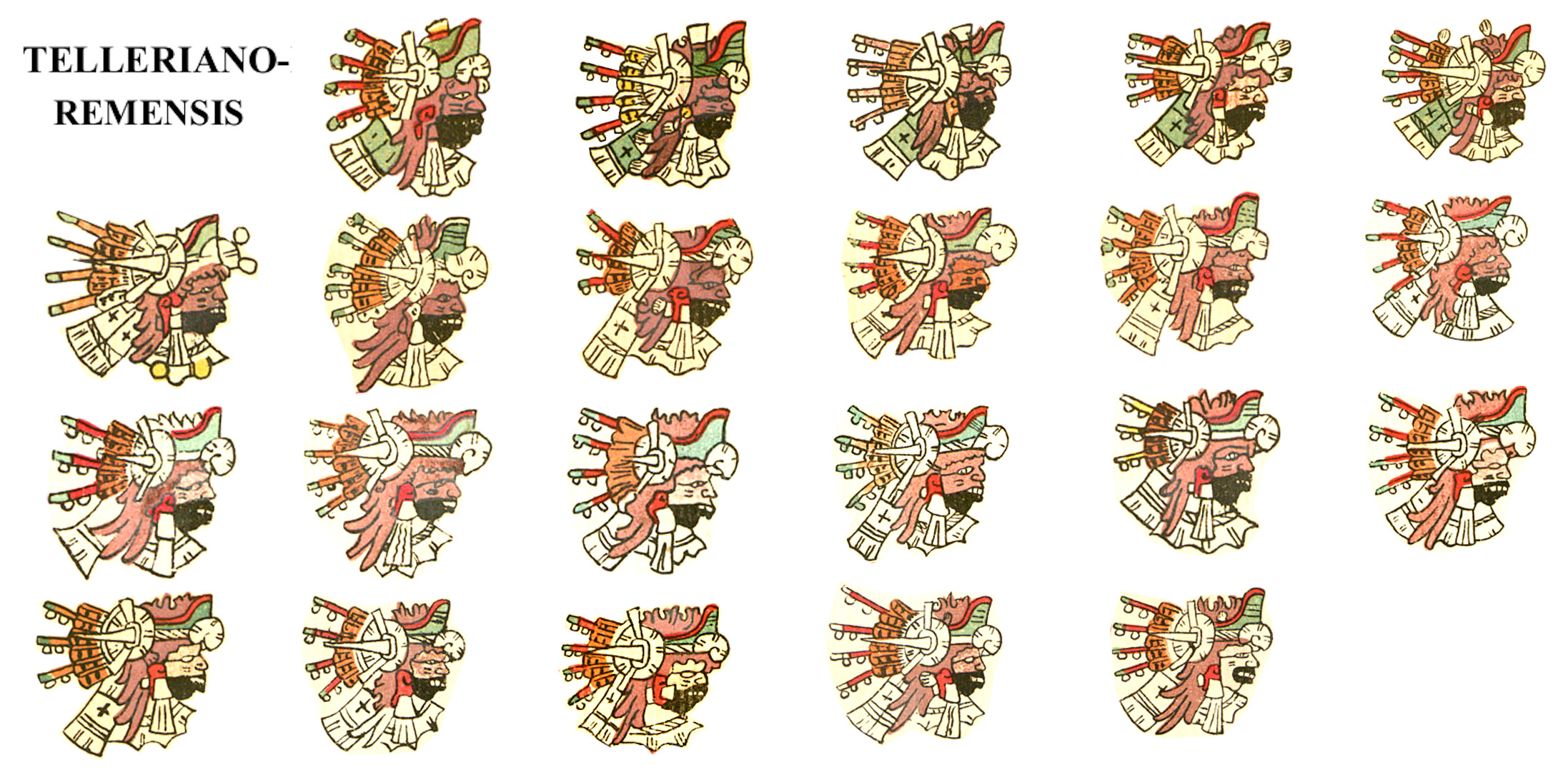

The secondary patron in these two codices, as also noted earlier, is unambiguously Centeotl, god of maize, as indicated by the bag of maize-ears on his back. In the interest of transparency, I admit to performing radical plastic surgery to make Centeotl look realistically human on a par with Mayauel. The two original images, while very similar to each other, were both far too sketchy (and short-armed) to hold their own against the elegance of the goddess:

In addition (or subtraction!), I omitted the white banner they inexplicably hold behind the fancy feathered one. Whatever it signifies, I don’t care. Meanwhile, the sloppy Rios image makes me wonder if maybe the Italian copy of the Aztec codex might have involved a number of artists, some more competent than others. The qualitative variation in Rios images is striking.

#

OTHER TONALAMATLS

The patron panel in Tonalamatl Aubin is replete with the motifs we saw in Codex Borgia, plus some. The figure of Mayauel is enthroned with a highly abstracted maguey on its back, and part of her headdress is in blue and white, but there is only a vague indication of a blue lower jaw. Curiously, she doesn’t hold a pulque bowl but an incense bag. The pulque brew-pot appears within the night symbol at the top.

The secondary patron on the left is again unidentifiable, except that he holds the same flowered banner as Centeotl in Tonalamatl Yoal, and wears that disturbing skewered heart. Is that banner enough to signify Centeotl? In any case, there’s no awkward white banner… New are the little couple at the bottom apparently having a great party—either drinking or regurgitating. At least they add a little drama to the tableau.

#

This patron panel for the Grass trecena in Codex Borbonicus is typically cluttered with symbolic items, among which are frothy pots of pulque, the brew-pot included in the night symbol like in Tonalamatl Aubin, a little guy on the lower right apparently vomiting, and another on the lower left with snake and shield who defies interpretation. I’m intrigued by the fat spider, a creature usually encountered in connection with Mictlan, the Land of the Dead. A good priest or calendar diviner would probably know what to make out of this mixed bag of symbols.

The image of Mayauel on the left is particularly striking with that special blue on the maguey leaves and her whole face and body. The flowers in her headdress complete the personification of the plant, and the swatch of rope she holds is another important product of the maguey. The secondary patron on the right is a puzzle. He brandishes Centeotl’s banners, the white one included, and looking like Centeotl’s in Yoal, his headdress includes a skewer with two hearts—like a shish-ka-bob. But he carries no bag of maize, so again we can’t be sure who he is. In any case, he’s a fairly impressive guy.

#

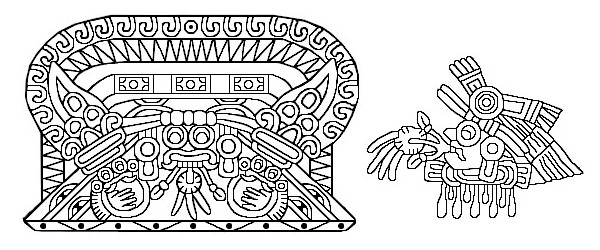

Speaking of impressive, in the Codex Vaticanus patron panel the out-sized pulque brew-pot is even more so than even the ornamented one in Codex Borgia, what with the mystical snake coiled around its base, its decorative cordage, and the overflowing frothy head.

As patron of the trecena, the smaller figure of Mayauel on the right takes second place to the pot, sitting now (awkwardly) within the blooming maguey. Her headdress contains another blue and white crest, and her blue lower face and nosepiece look a lot like those in the Borgia panel. We can assume that a blue lower face is emblematic of the goddess. Maybe it’s a cross-cultural reference to drinking oneself ‘blue in the face?’

On the left side, the secondary patron is even less identifiable, but I love his pointing approvingly at his foaming cup of pulque. Beneath him is another skewered heart for whatever it’s worth, but the white object hovering over his head is perfectly inscrutable. Once again, we need a calendar diviner (like Five Vulture) to sort these symbols out.

#

Perhaps the lesson to be taken from this review of Grass trecena is that secondary patrons aren’t actually all that important, whoever they may be. Consequently, I probably shouldn’t be taken to task for omitting them from my old tonalamatl. My earlier ignorance seems forgivable now. I just wish I knew what those shish-ka-bobs are all about.

#

UPCOMING ATTRACTION

The calendar’s ninth trecena will be that of Snake, the principal patron of which is the transcendent god of fire Xiuhtecuhtli. Stay tuned.

#