The thirteenth trecena (13-day “week”) of the Aztec Tonalpohualli (ceremonial count of days) is called Earthquake (or Motion/Movement) for its first numbered day, which is the 17th day of the veintena (20-day “month”). In the Nahuatl language Earthquake is Ollin, and it’s known as Kab’an in Yucatec Maya and No’j in Quiché Maya.

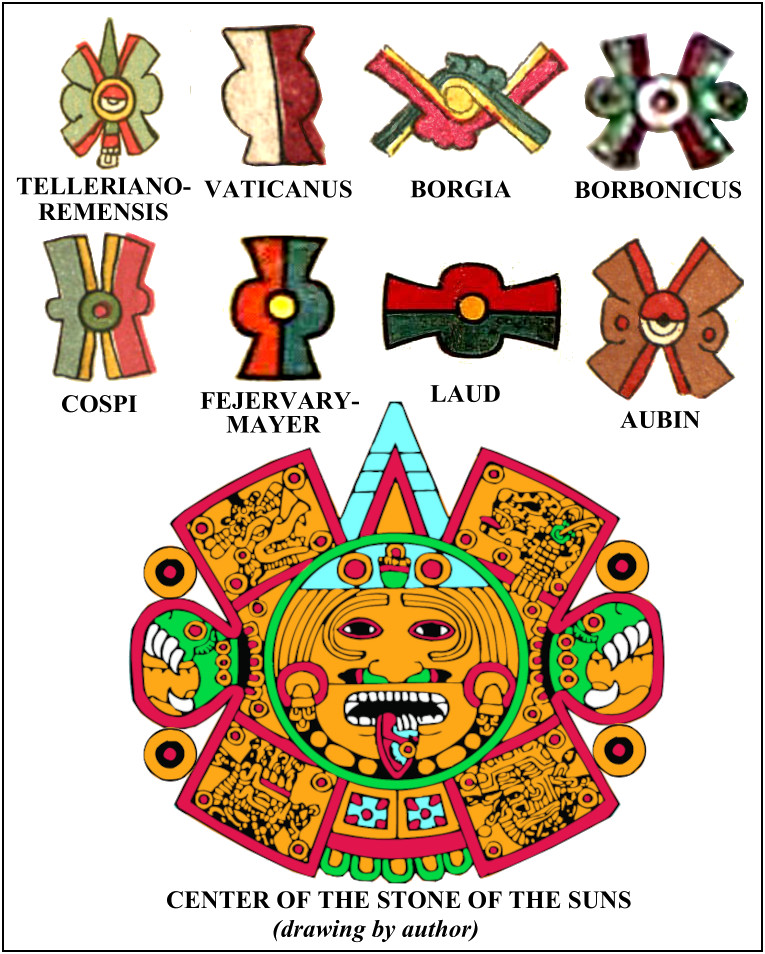

Nineteen of the 20 day-signs of the vientena are glyphs based on concrete things or items, but the one for the day Earthquake is something else entirely, the symbol of an abstract “think” (i.e., a thought or concept). The lobed or flanged form can rotate as needed but varies stylistically across the codices, while usually retaining a similar shape in each one:

The enormously embellished symbol for Earthquake in the center of the Stone of the Suns is literally the day-sign “Four Earthquake,” day-name of the current Fifth Sun (which occurs in the Jaguar Trecena), and the central face is that of its titular deity Tonatiuh. Within its four lobes are the day-names of the previous four Suns (starting on upper right and moving counterclockwise): Four Jaguar, Four Wind, Four Rain, and Four Water.

The divine patron of the day Earthquake is Xolotl, god of the Evening Star, who will be seen later as patron of the Vulture Trecena. Sometimes called Quetzalcoatl’s evil twin, he’s the deity of malice, treachery and danger and represents the darkness of the unconscious.

PATRON DEITY RULING THE EARTHQUAKE TRECENA

The patron of the Earthquake Trecena is the far less dire goddess Tlazolteotl (Goddess of Filth), whom we’ve already seen as a patron of the Deer Trecena (in Borgia) and Reed Trecena (in Yoal). Her unprecedented patronage of two (or three) trecenas suggests that she’s one of the most important (powerful) deities in the Aztec pantheon. To recap, Tlazolteotl is goddess of fertility and sexuality, motherhood, midwives, and domestic crafts like weaving, as well as patron of witchcraft and fortune-tellers and of lechery and unlawful love, including adulterers and sexual misdeeds. She cures diseases, particularly venereal, and as the goddess of purification and bathing, forgives sins. People confess their sins to her only once in their life, usually at the very last moment, and besides that rite (which Spanish clergy recognized as parallel to their sacrament of confession), her rituals include offerings of urine and excrement. One of several earthmothers, Tlazolteotl is reputedly the mother (sire unknown) of the maize deities Centeotl and Chicomecoatl. She’s also 7th lord of the night and patron of the mystical number 5.

AUGURIES OF EARTHQUAKE TRECENA

By Marguerite Paquin, author of “Manual for the Soul: A Guide to the Energies of Life: How Sacred Mesoamerican Calendrics Reveal Patterns of Destiny”

https://whitepuppress.ca/manual-for-the-soul/

The theme of this trecena is evolutionary movement. It’s associated with the opening and closing of major eras within the Maya Calendar system and aligned with re-birth or emergence, which can sometimes manifest as world-shaping beginnings and endings. Traditionally this was a generative period during which “confessional rites” were conducted, possibly tied in with the fertile forces of “evolutionary movement” that can bring forth significant change. This would be a good trecena for “stock-taking” and for making “evolutionary” leaps forward.

Further to how these energies connect with world events, see the Maya Count of Days Horoscope blog at whitepuppress.ca/horoscope/ Look for the Kab’an trecena.

THE 13 NUMBERED DAYS IN THE EARTHQUAKE TRECENA

The Aztec Tonalpohualli, like the ancestral Maya calendar, is counted through the sequence of 20 named days of the agricultural “month” (veintena), of which there are 18 in the solar year. Starting with the 17th day of the preceding veintena, 1 Earthquake, this trecena continues with 2 Flint, 3 Rain, 4 Flower, 5 Crocodile, 6 Wind, 7 House, 8 Lizard, 9 Snake, 10 Death, 11 Deer, 12 Rabbit, and 13 Water.

There are only two relatively special days in the Earthquake trecena:

Four Flower (in Nahuatl Nahui Xochitl)—important for the Maya as 4 Ajaw, though some of its significance may have survived into later cultures. Dr. Paquin advises that the energy of the day was associated with the beginning and ending of eras. For the Maya, their Fourth World was created on 4 Ajaw in 3114 BC, and after a long-count cycle of 5126 years, a 4 Ajaw day brought the conclusion to that era on 12/21/2012 when a new Maya Calendar era began.

Twelve Rabbit (in Nahuatl Mahtlactli ihuan ome Tochtli)—day-name of the Rabbit in the Moon as seen in the Borgia Death Trecena. I’ve no idea how the day may have been celebrated, but as a Rabbit-god of intoxication, Twelve Rabbit was likely the deity of lunacy (moon-madness).

THE TONALAMATL (BOOK OF DAYS)

Several of the surviving so-called Aztec codices (some originating from other cultures like the Mixtec) have Tonalamatl sections laying out the trecenas of the Tonalpohualli on separate pages. In Codex Borbonicus and Tonalamatl Aubin, the first two pages are missing; Codex Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Rios are each lacking various pages (fortunately not the same ones); and in Codex Borgia and Codex Vaticanus all 20 pages are extant. (The Tonalpohualli is also presented in a spread-sheet fashion in Codex Borgia, Codex Vaticanus, and Codex Cospi, but that format apparently serves other purposes.)

TONALAMATL BALTHAZAR

As described in my earlier blog The Aztec Calendar – My Obsession, some thirty years ago—on the basis of very limited ethnographic information and iconographic models —I presumed to create my own version of a Tonalamatl, publishing it in 1993 as Celebrate Native America!

As the patron of the Earthquake trecena, I based my Tlazolteotl rather loosely on the Codex Borbonicus patron panel (see below), at the time the only readily available image of the goddess. I didn’t realize that the frontal view was absolutely unique in Aztec iconography (meanwhile with a standard profile face). Much later I found a similar Codex Borgia example and a couple in Codex Laud, but Tlazolteotl seems the only deity ever to appear in a “crotch-shot,” which perhaps follows from her role as a mother-goddess. Certain female figures in Codex Nuttall sit with legs crossed in front but with upper body in profile.

I took the Borbonicus image as license to include the new-born infant but didn’t realize the symbolism of crescents and gave her a stepped nosepiece appropriate for Chalchiuhtlicue. The rest of her regalia is my invention, again inspired by figures in Codex Nuttall. I’m not sure how she wound up with that menacing Borgia mouth, but many women have admired this image.

#

TONALAMATL BORGIA (re-created by Richard Balthazar from Codex Borgia)

In the Borgia panel, the only symbolic markers for Tlazolteotl on the left are the three crescents on her clothing, the crescent nosepiece, and the black coloration around her mouth (indicative of her eating the filth of peoples’ sins). Those were apparently considered sufficient to distinguish her under the fairly standard details of regalia and throne.

In the center, the mysterious snake (with stars) was a real puzzle for me until a knowledgeable friend explained that white-striped, red snakes are sacrificial; the odd brown and grey strips of jaguar fur below are fire and smoke. (See them also in central temple scene in the Crocodile trecena.) But why does the snake have three fangs? Also, those aren’t three tongues—just the long bottom one is. I believe that the two brown items represent the snake’s hissing, like the animal-howl symbols in the Deer, Flower, and Monkey trecenas. The large central figure is probably equivalently significant for divination as the other two elements in this elegant panel.

On the right, the third element of temple with ornate bird was also a puzzle for me until I looked closely and realized that under all that stylization was a vulture. The head is much like that of the Borgia day-sign for Vulture (Cozcacuauhtli)—with ears no less! The clincher was the dirty beak. Species identification aside, the vulture’s divinatory significance must come from its meaning as a day-sign: cleansing, purification, and prosperity—reinforcing those defining characteristics of Tlazolteotl. (She’s also a goddess of luxury, which is why I gave my version a fancy fan.)

#

TONALAMATL YOAL (compiled and re-created by Richard Balthazar on the basis of

Codex Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Rios)

The slapdash sketch of Tlazolteotl in Codex Telleriano-Remensis looks like it was drawn by an artist either with palsy or psychedelically inebriated, distorting her proportions and features and loading her down with identifiers. In “copying” it, the poor Italian artist-copyist for Rios tried with limited success to simplify the mess. I’ve given her more realistic and readable details like some in her bust as seventh Lord of the Night (top row, fourth from the left, and last on lower right). She’s one of the more complicated and enigmatic figures in Tonalamatl Yoal.

To allay any confusion about who she might be, there’s that billboard/banner on her back with 15 crescents, and for consistency, I gave her the standard crescent nosepiece. Reflecting her connection to luxury (mentioned above), she wears a long “granny” skirt with layers of tassels, as well as a sacred jaguar-pelt apron and bustle. This heavy skirt explains her unusual stance as though walking—instead of the standard dancing posture of most figures. The spindles and tassels in her headdress and on her earplug (like those in her image as Night Lord) indicate that she’s the patron of weaving, often called Ixcuina, goddess of cotton.

However, the top half of her body is clothed in the flayed human skin of a (female) sacrifice. See the dangling extra hands and flaccid breasts. Wearing a flayed skin is an attribute of the god Xipe Totec, but it occasionally adorns Tlazolteotl as well. The difference here is that her own body seems to have been flayed (arms and legs), which means that maybe she’s wearing her own skin. How’s that for a horrific scenario? Though the flesh marks might resemble the speckles on her cotton tassels, I’ve given them a red overtone like the flaying marks on Itztlacoliuhqui in the Lizard trecena. The only way I can explain those little shells stuck all over her is that perhaps they’re what was used to flay her. Ouch!

Moving on, consider that bowl of offerings she extends (to the other figure?), a grisly collection of dead baby-head, severed hand, heart, and probably the tail-end of a sacrificed snake. A sharp contrast to her simple, elegant image in Borgia, this gruesome detail is best overlooked. But it’s impossible to overlook the strange circular, apparently transparent, item that magnifies part of her hand and the offering bowl, an enigmatic anachronism if I’ve ever seen one. We have no evidence that the Aztecs had or knew anything about lenses. The Rios artist must have thought the same because this mysterious detail was omitted in that copy. Kudos to whomever can explain this weirdness. Or is this just more psychedelic inebriation?

Assuming that whoever drew the T-R goddess also drew that codex’s image of the “bird-man,” a page which is sadly missing from the document, the Rios copyist probably had to deal with another lot of hallucinatory details. So, we can’t be sure how accurately this guy got copied. In particular, the bird-costume doesn’t relate to any recognizable avian species.

Its brown plumage looks like that of the eagle in the Monkey trecena, but that topknot is outrageously unreal, and the black-striped eye (which may well have been in the T-R original) doesn’t help at all. Guessing from the bird in Borgia, maybe this is supposed to be a vulture too, the fantasy of an artist unfamiliar with the species. There are no vultures in Mexico (or in Italy) that even vaguely resemble this big bird. Also, all vultures seem to have longer, thinner beaks, usually of whitish or darker hue, not gold.

The Rios copy explicitly identifies the figure as Tezcatlipoca, and so a vulture makes sense as the disguise of this invisible deity, since he’s never shown as an eagle. Only that be-ribboned circular pendant is (not exclusively) a diagnostic, but the long nose-bar is uncharacteristic. The artist gave the figure a muddy greyish skin and brownish gold face, but I decided to use the vaguely mauve tone of Quetzalcoatl’s skin in the Jaguar trecena to indicate the supernatural status of this disguised deity.

For divinatory purposes, I expect we should consider themes that the day Vulture shares with Tezcatlipoca, whatever they might be. Besides this appearance in a vulture-suit and his weird epiphany in the Borgia Lizard trecena to support his nagual Itztlacoliuhqui, the invisible Tezcatlipoca will show up again later as the Black One in the Borgia Eagle trecena and in his jaguar disguise in the other tonalamatls. In other trecenas he appears only as a nagual, like Tepeyollotl in the Deer trecena and Chalchiuhtotolin in the Water trecena. Occurring (even in disguise or symbol) in four trecenas must mean that Tezcatlipoca is about as big a shot as a deity can get. He and Tlazolteotl together make a major power couple.

#

OTHER TONALAMATLS

In the patron panel in Tonalamatl Aubin, we find many already familiar motifs in its typically careless execution, both with Tlazolteotl on the right and the other two symbolic elements, though reversed from Borgia’s layout. The deity’s accoutrements (including a flayed skin) are quite like those in Yoal, as well as that honking crescent nosepiece just so we don’t forget who she is. New is the symbol of her lascivious sexuality: a snake under her throne. Note she even has an offering bowl with a heart and severed hand. I question her need for that loincloth—and in particular, those two little footprints in the upper right. My intuition says they signify ritual pilgrimages to her holy places. Any ideas about the little loop of ribbon over her head?

The juxtaposed temple on the left, far less ornate than the one in Borgia, holds another bird of anomalous species, but presumably a vulture. It’s crowned with more outrageous plumes and as an earplug (without an ear!) wears a smoking mirror, trademark of the ephemeral Tezcatlipoca. So, we’re seeing some pretty consistent themes—at least until we look at the central element reflecting the sacrificial snake in Borgia. Here there’s no snake but two intertwined “beings,” the taller one, who may be flayed and wears a crude Ehecatl (life) mask, holds aloft in his right hand an outsized xiuhcoatl (fire-serpent) weapon, symbol of divine power, and carries in his left an incense bag for worship. This is where I must leave further interpretation to you.

#

In the patron panel in Codex Borbonicus, the monumental full-frontal image of Tlazolteotl, as mentioned earlier, is the source of my own image of the goddess, though I obviously ignored her emphatic iconography—like the dozens of crescents, voluminous draperies of cotton (a true Cotton Queen!), several decorative spindles, and grisly details of the flayed skin she wears over her own flayed body. Missing are the many shells (flaying tools) we saw in both Yoal and Aubin, but other familiar elements can be seen in the scattered conglom: offerings of a head and heart (lower right), sacrificed snake (lower left), and pilgrimage footprints (top center). Particularly significant is the day-sign 9 Reed by her left foot—her sometimes day-name. The spilling bowl of water (upper right) clearly relates to her purification function.

The ornamental bird on the right (with human hands and feet) has generic brown plumage, but its head (apart from the familiar black stripe) looks like a standard eagle. Nevertheless, this many-plumed bird again must be a vulture disguise of Tezcatlipoca—judging by the be-ribboned circular pendant and smoking mirror trademark on its head. The panel also reflects the tripartite layout of Borgia and Aubin with the central pair of intertwined serpent and centipede. The serpent here represents life (like the Ehecatl figure in Aubin), and the centipede is an ancient symbol (since Maya times) of the Underworld.

#

The Codex Vaticanus artist apparently opted for simplicity. The goddess has only the blackened mouth and crescent nosepiece to identify her, and she’s wrapped in a corpse-bundle, maybe as a reflection of Itztlacoliuhqui in the Lizard trecena. Little attention was devoted to the sacrificial snake in the center, and the bird in the decorative temple is evidently a real vulture—note the dirty beak. Its red topknot and clawed wings, however, are ornithologically hard to explain.

#

This review of the Earthquake trecena indicates that we need to add a new (stealth) patron for the time period, the invisible, transcendental Tezcatlipoca (See my Icon #19.)—in his disguise as a vulture. His close association with Tlazolteotl makes me wonder if maybe there’s some mythological hanky-panky going on between the two of them. After all, she’s also the patron of promiscuity and adultery, and he’s a famous seducer. (Might he be the father of Centeotl and Chicomecoatl?)

###

You can view all the calendar pages I’ve completed up to this point in the Tonalamatl gallery.