The nineteenth trecena (13-day “week”) of the Aztec Tonalpohualli (ceremonial count of days) is called Eagle for its first numbered day, which is the 15th day of the veintena (20-day “month”). In Nahuatl, Eagle is Cuauhtli. It was known as Men (Eagle, Sage or Wise One) in Yucatec Maya and Tz’ikin (Eagle) in Quiché Maya.

Ever since the Maya, the day Eagle has signified bravery, lofty ideals, acuity of vision and mind. The Eagle was seen as an avatar of the sun and emblematic of high authority. The elite order of Eagle Knights was prominent in Aztec society. The day-sign was anatomically connected to various parts of the body, including the right ear and right foot. The patron of the day Eagle is Xipe Totec, the god of Spring and renewal, who was seen as patron of the Dog Trecena.

PATRON DEITY RULING THE EAGLE TRECENA

Xochiquetzal (Flower Feather) is the ever-young goddess of love, beauty, sexuality, and fertility. She protects young mothers in pregnancy and childbirth and is patron of weaving, embroidery, artisans, artists, and prostitutes. Her day-name is Ce Mazatl (One Deer). Reflecting her intense sexuality, among her several reputed husbands/lovers were her twin brother Xochipilli, Tlaloc, Tezcatlipoca, Centeotl, and Xiuhtecuhtli. However, despite her patronage of fertility, I’ve not seen any reports of progeny. Very recently, I was advised that Tezcatlipoca is a possibly secondary/minor patron of the trecena in one of his many nagual disguises.

AUGURIES OF THE EAGLE TRECENA

By Marguerite Paquin, author of “Manual for the Soul: A Guide to the Energies of Life: How Sacred Mesoamerican Calendrics Reveal Patterns of Destiny”

https://whitepuppress.ca/manual-for-the-soul/

Theme: Supremacy/War, Lofty Vision. The juxtaposition of the “supremacy” oriented energies of the Eagle with a patron energy of a goddess aligned with artistry and creativity, brings to mind the idea that women who died in childbirth were seen as “warriors” and, like warriors who died in battle, were esteemed for their bravery. The “creativity” component may refer to the valor and creativity involved in bringing forth new life. This combination of energies places emphasis on the courage needed to overcome obstacles and move life forward despite enormous challenges. Power, military strength, and transformative action are often highlighted during this period.

Further to how these energies connect with world events, see the Maya Count of Days Horoscope blog at whitepuppress.ca/horoscope/ Look for the Men (Eagle) trecena.

THE 13 NUMBERED DAYS IN THE EAGLE TRECENA

The Aztec Tonalpohualli, like the ancestral Maya calendar, is counted through the sequence of 20 named days of the agricultural “month” (veintena), of which there are 18 in the solar year. Starting with 1 Eagle, it continues with: 2 Vulture, 3 Earthquake, 4 Flint, 5 Rain, 6 Flower, 7 Crocodile, 8 Wind, 9 House, 10 Lizard, 11 Snake, 12 Death, and 13 Deer.

There are a few special days in the Eagle trecena:

One Eagle (in Nahuatl Ce Cuauhtli) – Day-name of one of the Cihuateteo, spirits of women who died in childbirth. It’s also associated with Cihuacoatl (Snake Woman), a goddess of fertility, motherhood, midwives, and sweat baths.

Three Earthquake (in Nahuatl Yeyi Ollin) and Seven Crocodile (in Nahuatl Chicome Cipactli) – Noted in the Florentine Codex as special days for bathing newborns and celebrating births.

THE TONALAMATL (BOOK OF DAYS)

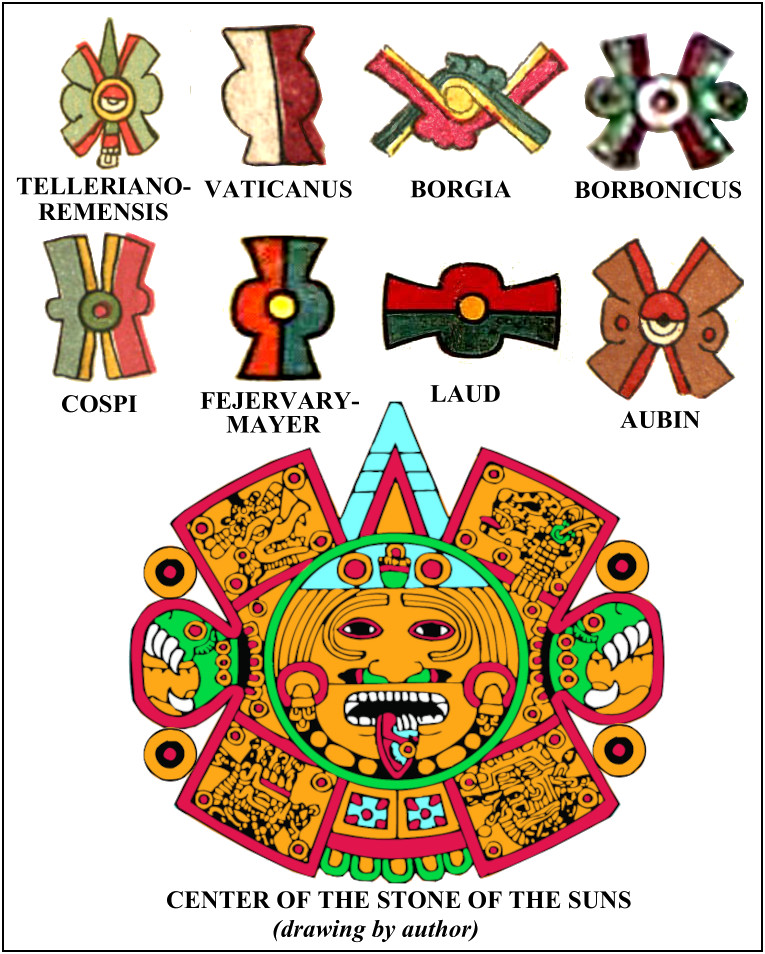

Several of the surviving so-called Aztec codices (some originating from other cultures like the Mixtec) have Tonalamatl sections laying out the trecenas of the Tonalpohualli on separate pages. In Codex Borbonicus and Tonalamatl Aubin, the first two pages are missing; Codex Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Rios are each lacking various pages (fortunately not the same ones); and in Codex Borgia and Codex Vaticanus all 20 pages are extant. (The Tonalpohualli is also presented in a spread-sheet fashion in Codex Borgia, Codex Vaticanus, and Codex Cospi, but that format apparently serves other purposes.)

TONALAMATL BALTHAZAR

As described in my earlier blog The Aztec Calendar – My Obsession, some thirty years ago—on the basis of very limited ethnographic information and iconographic models —I presumed to create my own version of a Tonalamatl, publishing it in 1993 as Celebrate Native America!

When I drew Xochiquetzal so long ago, I knew only her many-plumed image from Codex Borbonicus (see below) and simplified that model, omitting her lascivious snake. I replaced the flower stalks sticking out of her mouth with one of the few iconographic conventions I knew of, the song-symbol cuciatl. However, I mistakenly turned the front stalk from under her throne into a flower when it was in fact a centipede representing the Underworld.

#

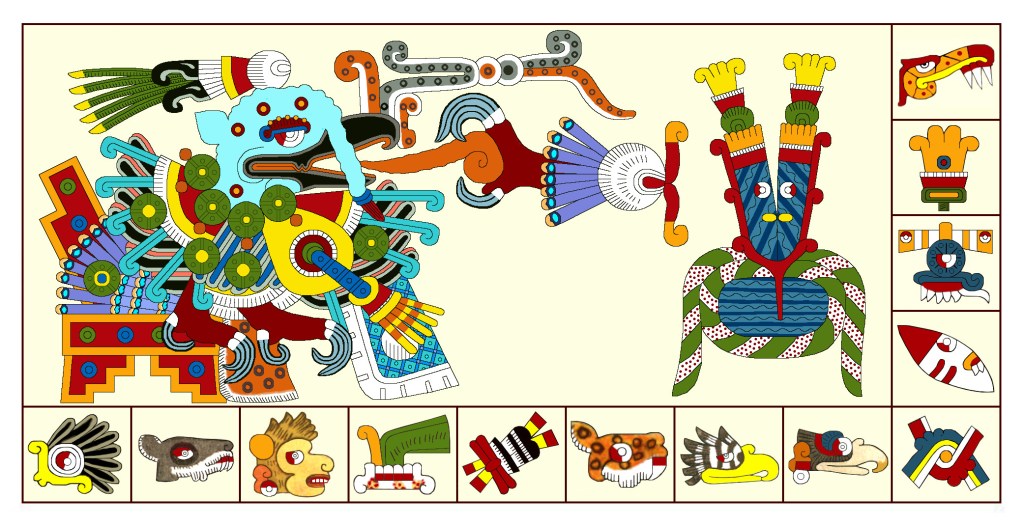

TONALAMATL BORGIA (re-created by Richard Balthazar from Codex Borgia)

The Codex Borgia version of Xochiquetzal on the left is downright punk with her intricate facial tattoos, but she displays no specific emblems of her divine identity. In fact, her Earth Monster headdress would be more appropriate for Chalchiuhtlicue. The matrix in the lower center could suggest her patronage of weaving, but I think it’s in fact a game-board for patolli because she’s also patron of gaming. The four hemispheres may be playing pieces for the game.

At first, I was confused by the lack of emblems specific to Tezcatlipoca on the figure on the right—other than the black body and smoky curls around his eye. Then a knowledgeable friend advised that this was in fact a nagual of the otherwise invisible Tezcatlipoca, Ixtlilton (Small Black Face), also known as Tlaltetecuin (Lord of the Black Water Tlilatl). The symbolic item at top center is his scrying bowl or jar of dark water used for hydromancy, diagnosing ailments and prescribing cures. A gentle god of medicine and healing specifically in relation to children, Ixtlilton brought them peaceful sleep at night. Like Tezcatlipoca, Ixtlilton was a deity of divination, Tezcatlipoca consulting his obsidian mirror, and Ixtlilton studying reflections in dark water. He was also a god of dance and music sometimes called the brother of Five Flower (a nagual of Xochipilli)

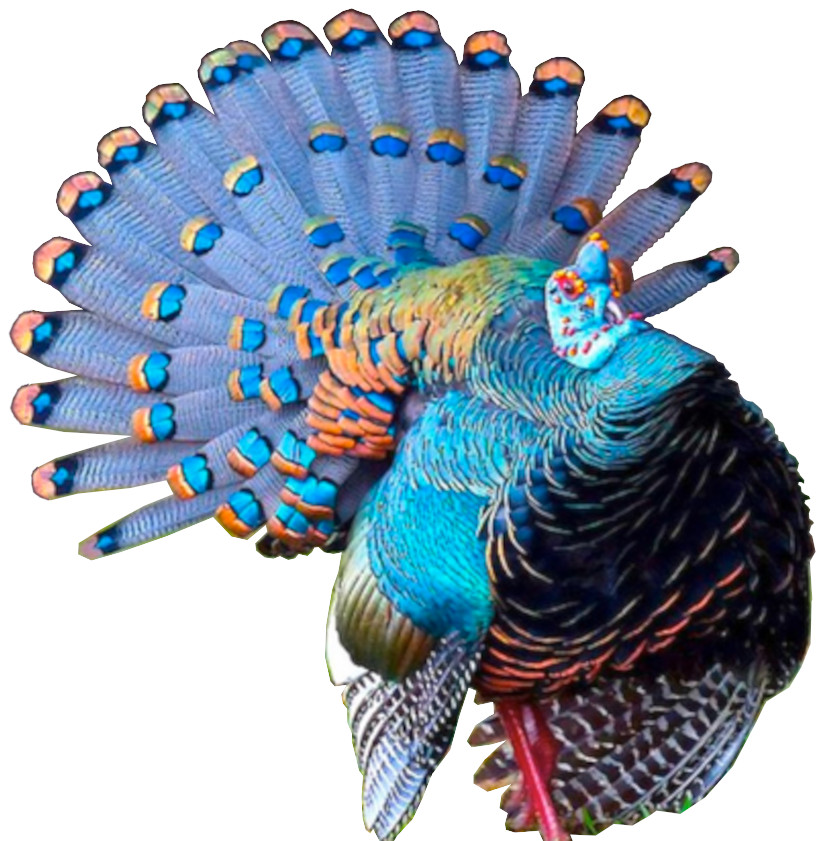

The divinatory relationship between Xochiquetzal and Tezcatlipoca isn’t clear to me, other than in their being erstwhile consorts. I may not have my mythological wires straight, but I gather Xochiquetzal was once upon a time the wife of the Storm God Tlaloc (see the Rain trecena) who ruled in the Third Sun (Four Rain), a happy era perhaps set historically in ancient Teotihuacan. However, the nefarious Tezcatlipoca abducted her, and Tlaloc flew into an inordinate rage, destroying his idyllic world with a rain of fire (volcano). Its poor people became butterflies, dogs, or birds, some say turkeys. Afterwards, Tlaloc apparently married Chalchiuhtlicue (see the Reed trecena), who became the ruler of the Fourth Sun (Four Water). Meanwhile, the philandering Tezcatlipoca apparently moved on to an affair with Tlazolteotl (see Deer and Earthquake trecenas). Quite a family saga…

#

TONALAMATL YOAL (compiled and re-created by Richard Balthazar on the basis of

Codex Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Rios)

The Yoal version of Xochiquetzal (on the left), like most deities in this tonalamatl, is loaded down with identifying motifs, including the facial tattoos. Here, she’s accompanied by an Underworld centipede under her throne, a libidinous snake looking out from between her thighs, a weirdly colored jaguar in her bustle, an eagle in her headdress, and an exorbitant display of quetzal plumes.

Xochiquetzal’s skirt is a beautiful example of her weaving prowess, and that blue thing in one of her left hands may well be a loom comb, a tool used to move weft yarns into place. That still doesn’t explain a similar (banded) object held by Chalchiuhtlicue in the Yoal Reed trecena, but it’s my best guess. In any event, this goddess is even grander than the Borbonicus image (see below) that inspired my own version.

The surreal deity on the right is not named in Codex Telleriano-Remensis, but in Codex Rios it’s labelled generically as Tezcatlipoca, its obvious nagual status indicated by a smoking mirror in the headdress. The anomalous creature in which the deity is disguised bears no relation to Borgia’s Ixtlilton or to any other known nagual of the Invisible One.

Some scholars suggest that this is a coyote—reflecting Tezcatlipoca’s talent for shape-shifting—like his walk-on appearance as a vulture in the Earthquake trecena. However, while this head might be canine, the ears are totally wrong, as are its eagle talons/claws and feline tail. Then there are those blue things stuck all over it (chips of turquoise or lapis?) which turn it into some mythical jeweled creature. Of course, such scholarly suggestions (like most scholarship) are simply authoritative guesswork, and I don’t require final answers to mysteries.

#

OTHER TONALAMATLS

As a mythical jeweled creature, that in Tonalamatl Aubin sports red, gold, and blue jewels. It’s clearly no coyote, looking more like a jaguar with anatomically proper claws though with too short a tail. Note also the contrast with the true jaguar pelt it sits on. Its sketchy headdress resembles in form that of Borgia’s Ixtlilton, but nothing about it suggests Tezcatlipoca. Just a regular old jeweled critter?

On the right side, an understated Xochiquetzal at least has a fat centipede under her throne and an eagle in her headdress but is sorely lacking in quetzal plumes and imagination in her facial tattoo. Oddly, I think that thing she holds with both hands is an animal-headed digging stick, which doesn’t seem to relate to any of her themes.

The square would seem to be another patolli board, and the ballcourt design in the upper left is a new emblem, reflecting Xochiquetzal’s additional patronage (along with Xochipilli’s) of the sacred ballgame tlachtli. The decapitated individual may indicate the traditional fate of losers at tlachtli. (I’m not aware of her predilection for that style of sacrifice otherwise. However, somewhere long ago I read of a ritual sacrifice to her of a female, the victim’s flayed skin being donned by her priestess. Oh, my, the wild and crazy things goddesses do in the privacy of their temples…)

#

The image of Xochiquetzal in Codex Borbonicus is one of the most famous in Aztec iconography, obviously a bit more subtle than my old one and not as exuberant as that in Tonalamatl Yoal. But she does have a rather sexy snake. The major item to note is that most of her feathers are red. Deities usually wear green quetzal plumes like those in the topknots here, and the quetzal apparently only has little red feathers on its breast. These big red feathers probably come from the scarlet macaw, a bird sacred to her brother/spouse Xochipilli.

Almost lost among the twenty ritual items, the de-emphasized jeweled beast is still anomalous: coyote-like ears but a jaguar tail and avian claws. Whatever it’s supposed to mean, I guess it does so minimally. The three symbolic motifs we saw in the Aubin panel, the patolli gameboard, beheaded ballgame loser, and schematic ballcourt, are grouped at the top of this panel. In the upper right corner is a reference to Xochiquetzal’s importance as a patron of sex. The couple modestly hidden behind a blanket is the standard symbol of marriage (or intercourse). Seen in the Yoal panel for the Crocodile trecena, it also appears in several other codices.

The other items of the conglom don’t bear discussion, except to note the Borbonicus fondness for scorpions which appear in many of its patron panels.

#

Once again, Codex Vaticanus closely reflects the elements of Tonalamatl Borgia. This Xochiquetzal again has complex tattoos and an Earth Monster headdress. However, now she clearly dominates the secondary figure of Ixtlilton, that nagual of Tezcatlipoca identified by the Black Water Tlilatl above. The position of his arms akimbo (very like his posture in the Borgia panel) reminds me of the dancing figure in the Borgia Flower trecena whom I took to be his purported brother Five Flower (Macuil Xochitl). That deity, this one, and the Borgia Ixtlilton all have unusual face-paint patterns around their mouths that suggest a brotherly relationship—or at least more identity confusion among the minor-deity crowd.

#

As far as patrons of the Eagle trecena go, these various naguals of Tezcatlipoca don’t seem to contribute much to the trecena’s themes of Supremacy/War and Lofty Vision. Maybe Ixtlilton and the jeweled beast really were included merely to reflect Xochiquetzal’s romantic history with Tezcatlipoca. After all, that would tie in well with her divine sexuality and beauty. Dr. Paquin also suggests that Ixtlilton/Tlaltetecuin (and the jeweled beasts) are acting as cheerleaders for Xochiquetzal, dancing to ward off harmful influences and maintain her high position of supreme strategist in oversight of the game of life-death-resurrection.

###

You can view all the calendar pages I’ve completed up to this point in the Tonalamatl gallery.