The third trecena (13-day “week”) of the Aztec Tonalpohualli (ceremonial count of days) is called Deerfor its first numbered day, which is the 7th day of the veintena (20-day “month”). In the Nahuatl language Deer is Mazatl, and it’s known as Manik’ in Yucatec Maya and Quej in Quiché Maya. As the only other large food-animal in Mesoamerica (the peccary and turkey being much smaller than either), the deer was important protein for the populations, and their relationship to this timid animal is celebrated in many codices, mostly of slaughtering it. The leg (haunch) of the deer is also a frequent motif. Each of the days (tonalli) represents a specific human body part, and the deer is connected with the right leg. Don’t ask why.

PATRON DEITIES RULING THE TRECENA

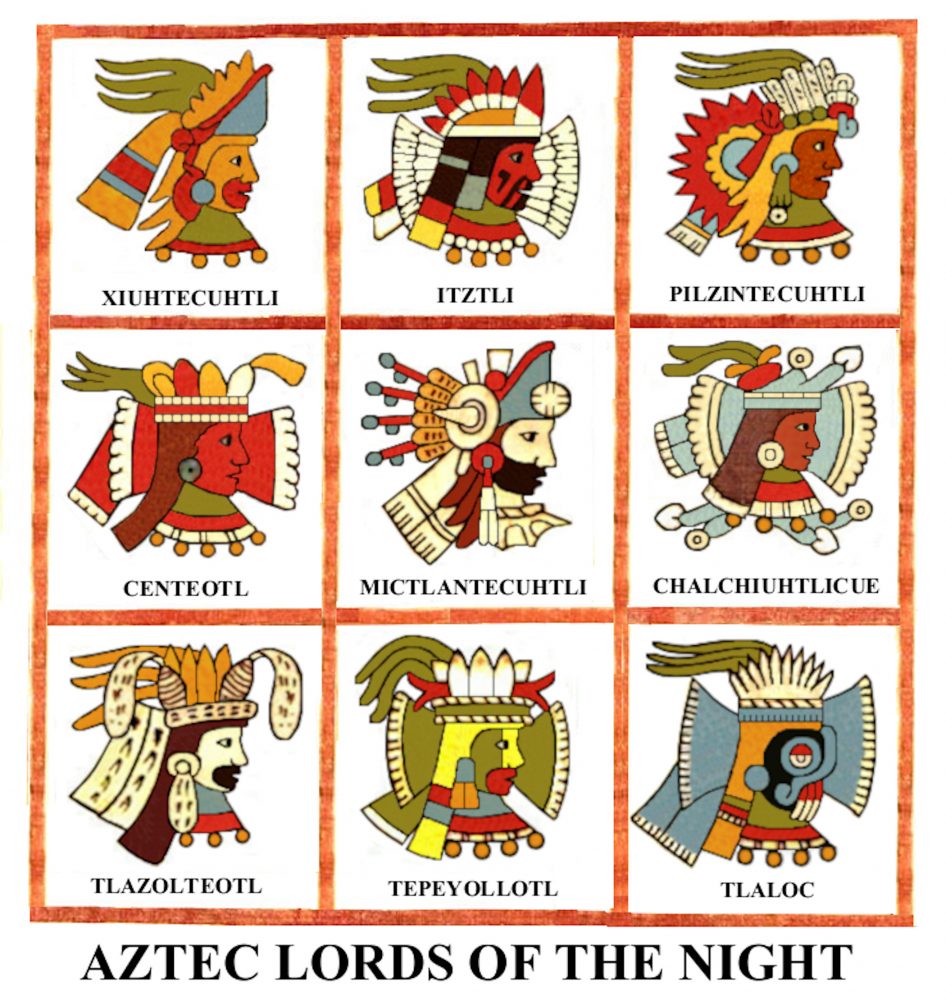

Tepeyollotl (Heart of the Mountain), god of caves and echoes, is the principal patron of the Deer trecena. He causes earthquakes, avalanches, and volcanos, and cures and causes diseases. A deity of witchcraft, he guards the entrance to Mictlan, the Land of the Dead. Possibly God L of the Maya, he may also be the primordial jaguar-man from even deeper in pre-history. As the Jaguar of the Night whose roaring heralds the sunrise, Tepeyollotl is a nagual of Tezcatlipoca, also known as the Lord of Jewels (mines) and 8th lord of the night. (See my Icon #17.)

There is doctrinal disagreement among the codices about the secondary patron of the Deer trecena. In Borgia and Vaticanus, it’s the goddess Tlazolteotl, but in the rest it’s Quetzalcoatl. This may well reflect regional calendar cults. Make of it what you will.

Tlazolteotl (Goddess of Filth) is goddess of fertility and sexuality, motherhood, midwives, and domestic crafts like weaving. On another hand, she is also the patron of witchcraft and fortune-tellers and of lechery and unlawful love, including adulterers and sexual misdeeds. She cures diseases, particularly venereal, and as the goddess of purification and bathing, forgives sins. (Her mouth is usually black from eating all those filthy sins). People confess their sins to her only once in their life, usually at the very last moment, and besides that rite (which Spanish clergy recognized as parallel to their sacrament of confession), her rituals include offerings of urine and excrement. One of several earth-mothers, Tlazolteotl is reputedly the mother of the maize deities Centeotl and Chicomecoatl, though divine genealogy is notoriously nebulous. She is also 7th lord of the night and patron of the number 5. According to some codex images, her day-name may be Nine Reed, which isn’t particularly pertinent to her divinatory significance.

Quetzalcoatl has been discussed at length as the sole patron of the previous Jaguar trecena. There remains little or nothing to add in conjunction with this appearance in a supporting role.

AUGURIES OF DEER TRECENA

By Marguerite Paquin, author of “Manual for the Soul: A Guide to the Energies of Life: How Sacred Mesoamerican Calendrics Reveal Patterns of Destiny”

Another strongly earth-oriented time period, this trecena is aligned with the general idea of “sacrifice and reconciliation.” It is often a period that calls for “give and take,” negotiation, cooperation, and even “forgiveness” in response to events of a high-stakes nature. The idea of the deer working with the hunter to provide a “giveaway” in order to sustain life is a metaphor that could apply here. Emphasis is on working together towards achieving “sacred balance” and harmony with the earth.

Further how these energies connect with world events, see the Maya Count of Days Horoscope blog at whitepuppress.ca/horoscope/. Note that the Maya equivalent is the Manik’ trecena.

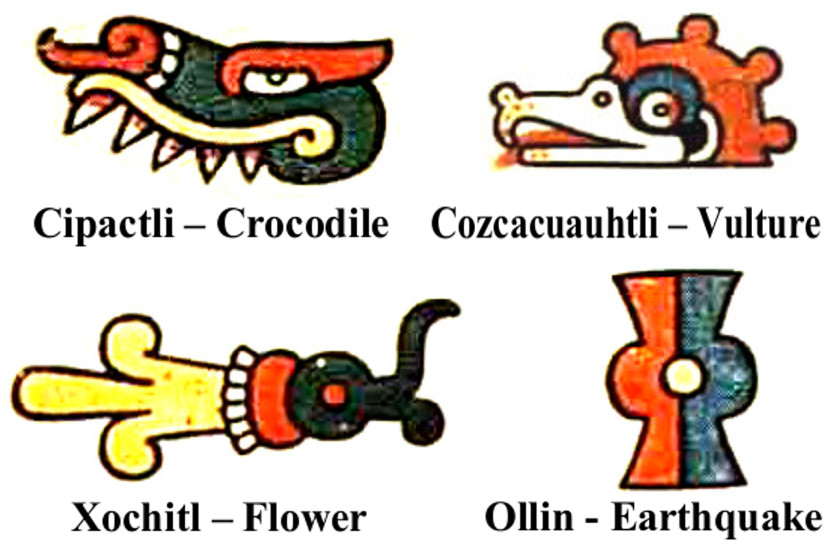

THE 13 NUMBERED DAYS IN THE DEER TRECENA

The Aztec Tonalpohualli, like the ancestral Maya calendar, is counted through the sequence of 20 named days of the agricultural “month” (veintena), of which there are 18 in the solar year. Starting with 1 Deer, the trecena continues 2 Rabbit, 3 Water, 4 Dog, 5 Monkey, 6 Grass, 7 Reed, 8 Jaguar, 9 Eagle, 10 Vulture, 11 Earthquake, 12 Flint, and 13 Rain—completing the count before finishing the veintena.

The Deer trecena contains at least two significant days:

One Deer (Ce Mazatl) may be the day-name of Xochiquetzal, the Flower Feather. (Lacking birth certificates, divine birthdays, like genealogies, often depend on cults and are no more certain or verifiable than those of mythical beings in western religious traditions.) She’s the ever-young goddess of love, beauty, female sexuality, and fertility—though her worship involves some surreally gruesome sacrificial rites. Xochiquetzal protects young mothers in pregnancy and childbirth, and is a patron of weaving, embroidery, artisans, artists, and prostitutes. As she’s the patron of the 19th trecena, Eagle, more of her scandalous mythology will be presented there.

One Deer (Ce Mazatl) is also the day-name of one of the Cihuateteo, warrior spirits of women who die in childbirth, who escort the sun from noon to its setting. Demons who cause seizures and insanity, after sunset they go to the crossroads to steal children and seduce men to adultery. Probably a nagualof Xochiquetzal, this one’s area of dangerous influence is beauty, sex, and love. In an image pairing the Cihuateteo with the male Ahuiateteo (gods of pleasure), she’s posed indicatively with Five Lizard (Macuil Cuetzpallin), the deity of sexual excess.

One Deer (Ce Mazatl) is also the day-name in the regional Mixtec tradition for the creative couple, Tonacatecuhtli and Tonacacihuatl (collectively Ometeotl), likely because of the connection between deer and the sun and provision of sustenance. (See the Crocodile trecena.)

Two Rabbit (Ome Tochtli) is the name-day of the principal god of drunkenness, Izquitecatl, one of the innumerable pulque gods known the centzon totochtin (400 rabbits). Among the other 399 rabbit-children of Mayauel and Patecatl who patronize every form of intoxication, alcoholic and herbal, one can name Tezcatzoncatl, Tlilhua, Toltecatl, and Tepoztecatl.

THE TONALAMATL (BOOK OF DAYS)

Several of the surviving so-called Aztec codices (some originating from other cultures like the Mixtec) have Tonalamatl sections laying out the trecenas of the Tonalpohualli on separate pages. In Codex Borbonicus and Tonalamatl Aubin, the first two pages are missing; Codex Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Rios are each lacking various pages (fortunately not the same ones); and in Codex Borgia and Codex Vaticanus all 20 pages are extant. (The Tonalpohualli is also presented in a spread-sheet fashion in Codex Borgia, Codex Vaticanus, and Codex Cospi, but that format apparently serves other purposes.)

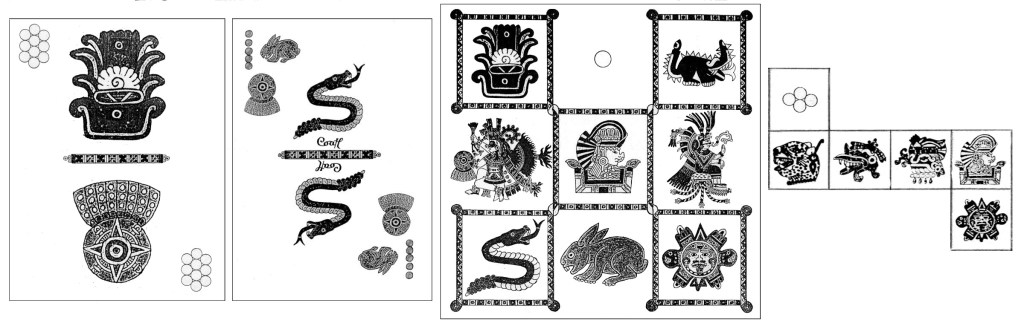

TONALAMATL BALTHAZAR

As described in my earlier blog The Aztec Calendar – My Obsession, some thirty years ago—on the basis of very limited ethnographic information and iconographic models —I presumed to create my own version of a Tonalamatl, publishing it in 1993 as Celebrate Native America! With no awareness of secondary patrons, I created an image of Tepeyollotl out of thin air to be the patron deity of the Deer trecena. Well, not quite: I knew what his name meant and that he was the god of volcanos. Working with motifs from Codex Nuttall, I concocted a fairly Mixtec design of angular and stepped patterns with an eruption in his headdress and an abstract pendant suggesting a “heart of the mountain.” Meanwhile, I must have been channeling deep Maya iconography to come up with his front-on cross-legged pose.

At this point, I should remark on the layout of the various tonalamatls, about which I had no clue thirty years ago. With the days arranged around three sides of the patron panel, mine was totally unorthodox, resulting in a roughly 3 X 4 height-width ratio. The authentic codices all present their tonalamatls on basically square pages. I’ll explain with each one how that works.

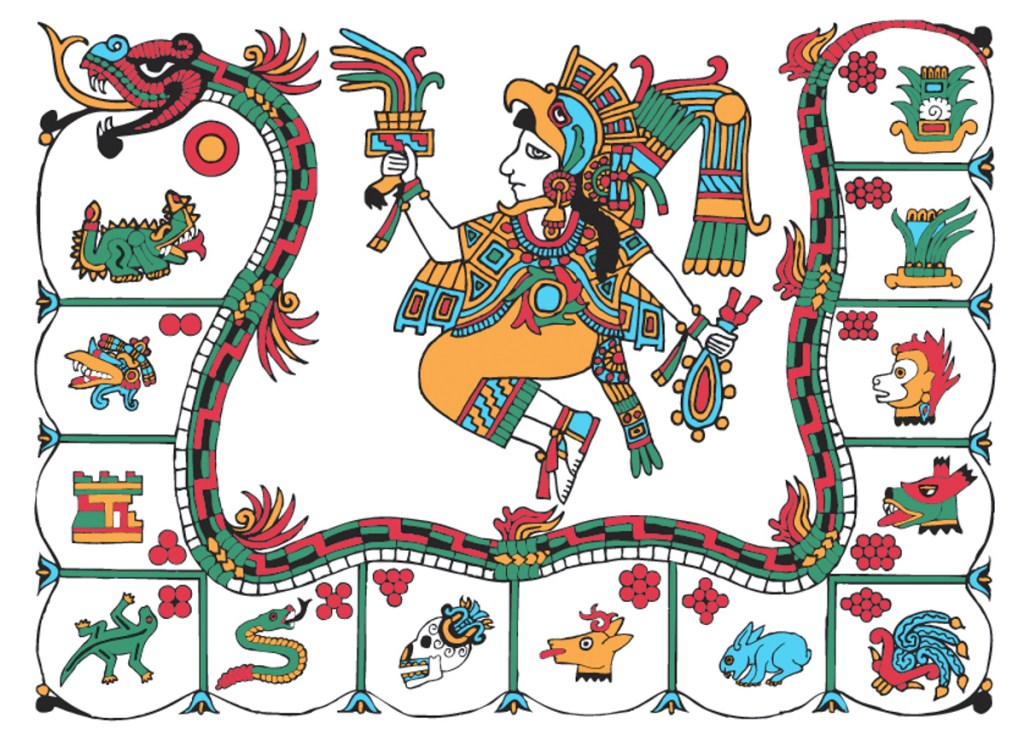

TONALAMATL BORGIA (re-created by Richard Balthazar from Codex Borgia)

The layout of the Borgia tonalamatl creates square pages by stacking two of the rectangular trecenas. The first ten trecenas run along the bottom of the pages, and then the second ten turns around in boustrophedon fashion to run on top back to the beginning. Thus, the 1st trecena (Crocodile) is capped with the 20th (Rabbit), the 2nd (Jaguar) with the 19th (Eagle), this 3rd (Deer) with the 18th (Wind), and so on. The progression of unnumbered days also switches direction with nine running across the bottom of the panel and four up the side.

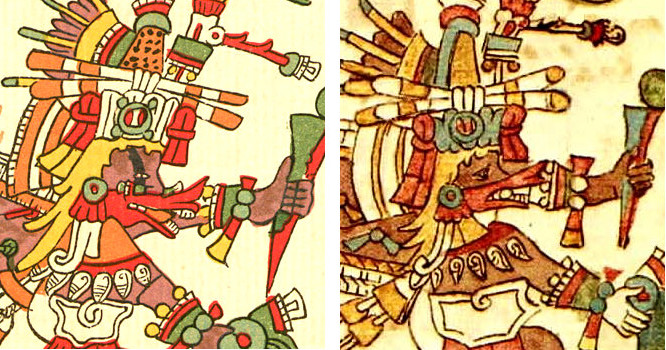

In this Borgia trecena Tepeyollotl appears as an in-the-flesh jaguar, which is in keeping with his being the Jaguar of the Night. Note the stars in his jungle/night-sky throne. The golden squiggles rising from his nose represent his roar. Once more, I can’t remark on the fancy paraphernalia floating around in the middle of the panel, except to point out the striped “power serpent” that lurks significantly at the bottom. I wonder what species of snake has that dark tail section. In some other codices the serpents are clearly the quintessential New World rattlesnake, but in Borgia the tails generally have only this dark point, though some flaunt ornamental plumes for tails.

The figure of Tlazolteotl as secondary patron of the trecena displays her emblematic black mouth, her usual curved nose ornament, and a weaving spindle in her headdress. The crescents on her skirt likely refer to her relationship with the moon (menstrual cycles). I have no idea why she’s holding a shield and handful of arrows, but the uniquely trussed-up figure she’s holding by the hair is presumably a sacrificial offering.

Note that the little guy has two right hands. Speaking of which, Tlazolteotl has two left hands, though her supposed right hand is impossibly contorted even for a left one. While I did nothing to “correct” this egregious example of “ideoplasty,” in the interest of aesthetic transparency, I must admit to some artistic plastic surgery on the goddess’s thumbs. In the original image they were both hugely over-sized, that on her left hand twice as large as anatomically proportional. I seriously doubt there was any deeper significance to the monstrous distortion.

TONALAMATL YOAL (compiled and re-created by Richard Balthazar on the basis of Codex

Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Rios)

The original two separate pages of Telleriano-Remensis and Rios are essentially square illustrations divided between days five and six, with ten tonalli across the top and three down the side. The lower sections of the separate pages were used for Spanish and Italian commentaries, respectively, with many notes intruding on the images, naming the tonalli, and coding the lords of the night as to good, bad, or indifferent luck. My compilation and re-creation have dispensed with all that archaic clutter.

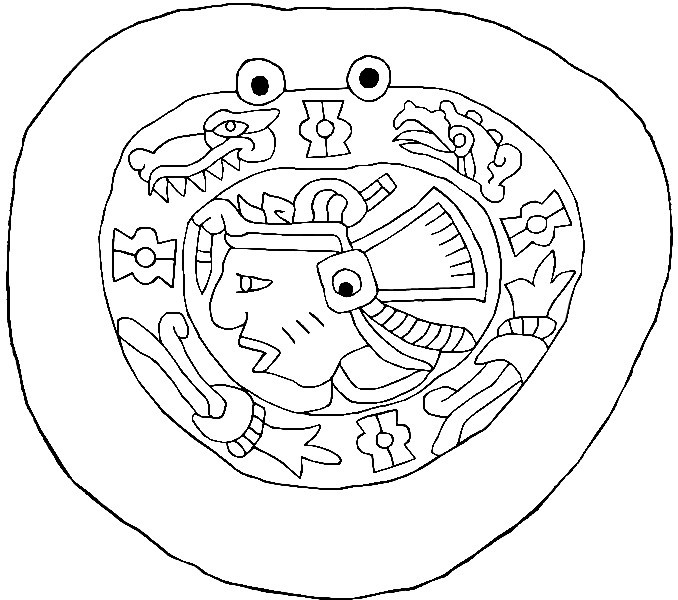

Observe that the god Tepeyollotl here is in a human form dressed in an entire jaguar pelt, head and claws included. I have greatly refined his face peering from the jaguar’s fanged mouth to reflect his image as 8th lord of the night, second from right on top above the day 9 Eagle. (Note that the third bust from right is Tlazolteotl as 7th lord of the night—with the black mouth and weaving spindles in her headdress.) Again, for transparency, I will admit to giving Tepeyollotl a “correct” right hand with the scepter. Here two left hands were just too jarringly ideoplastic! Otherwise, I strategically adjusted details and made only a few changes to his color scheme.

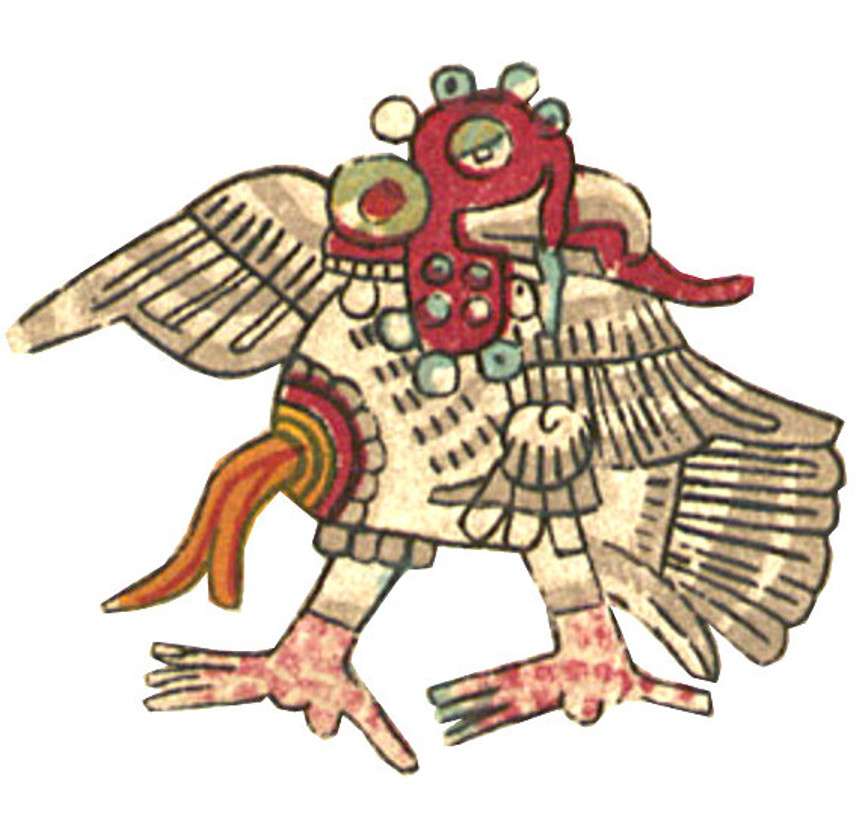

The figure of Quetzalcoatl as secondary patron is closely related to his image in the Jaguar trecena with outrageous headdress, curious medallion on his forehead, conch-shell pendant, and inexplicable “basket” on his back. Obvious differences are the lack of an Ehecatl-mask and black stripe down the face, the nautilus shell in his left hand (apparently symbolic of eternity), and the sacrificial victim held by the hair in his right hand. While the victim is quite in accordance with the trecena’s theme of sacrifice, it’s disturbing on two counts. Quetzalcoatl is famously opposed to human sacrifice, and the victim seems to be a child—normally sacrificed to Tlaloc.

OTHER TONALAMATLS

As the incomplete Codex Borbonicus and Tonalamatl Aubin start with the Deer trecena, I can now offer their patron panels for comparison. Apart from the differing secondary patrons and graphic styles, they’re remarkably consistent theologically.

The pages of Tonalamatl Aubin are laid out in squares with the patron panel in the upper left corner. Reversing the pattern of Borgia, the tonalli range from upper right with four down that side and nine across the bottom in ranks of four blocks. The first contain the numbered tonalli, the second the lords of the night, the third the lords of the day, and the fourth the totem-birds of the numbers. This results in a densely packed page, an effect only exaggerated by an extremely awkward cartoonish style of the images, particularly of the heads of the lords and birds.

Here Tepeyollotl is again an actual jaguar (oddly with only three claws on his forepaws). Apart from another “power serpent” (clearly a rattlesnake), the central paraphernalia is different than that in Borgia, though the conch is a frequent motif. Quetzalcoatl is recognizable as the secondary patron by his simplified headdress, black face-stripe, stylized conch-shell pendant, and in particular by the cross symbols on his sandals. The item in his right hand isn’t recognizable as a nautilus shell, but the victim held by the hair in his left is consistent iconography—and may also be a child. It’s amusing to note the blue finger- and toe-nails.

#

The pages of the tonalamatl section in Codex Borbonicus are also laid out in squares with patron panels in the upper left corners. However, its tonalli range from the lower left with seven across the bottom and six up the right side in ranks of two blocks. In the first blocks are the numbered tonalli with the lords of the night, and in the second are the lords of the day with respective totem-birds. While the style of the relatively large Borbonicus patron panels is ornate and colorful (with a superbly bright shade of blue), the surrounding small figures of tonalli, lords, and birds are so schematic that they’re difficult to distinguish. Nevertheless, the overall effect of the trecena pages is quite dramatic.

The Borbonicus Deer trecena is the third with Quetzalcoatl as secondary patron. Here the figure is very like the deity in Tonalamatl Yoal, including all the usual insignia, conch pendant, nautilus shell, and childlike sacrificial victim, but his face is the tri-color we saw earlier in the Borgia and Vaticanus images of the god in the Jaguar trecena. The principal patron Tepeyollotl is a hugely ornamented living, roaring jaguar with human hands (two lefts!) and right foot; to indicate that he’s a nagual of Tezcatlipoca, his left foot is replaced by a mystical smoking mirror. Generally indicating divinity, Tepeyollotl’s be-ribboned pendant is also worn by Xiuhtecuhtli, Xipe Totec, Chalchiuhtotolin, and many other deities.

The surrounding paraphernalia is mostly familiar, like the conch and serpent, but new are the fat spider and the sacrificial knife on the upper right. The containers of unidentifiable “stuff” are complicated by damage to the one on the lower right. The smudge continued along under Quetzalcoatl’s feet obscuring apparent Spanish annotations, which were also inserted into the border blocks to count the tonalli and name them. (Though I cleaned up that smudge, I held off doing any “repairs” to these images, but it was sorely tempting.)

#

In the previous Crocodile and Jaguar trecenas, we saw the peculiar, again cartoonish style of Codex Vaticanus, and here it is again in the patron panel for the Deer trecena. Similarly simplistic, the unnumbered tonalli run from the lower right with seven up that side and the remaining six across the top. The resulting square page is dominated by the large patron panel to much the same degree as in a Borgia trecena.

The presence here of Tlazolteotl as secondary patron is more evidence of a close relationship between the Vaticanus and Borgia codices. She is identified only by the black mouth, but she holds the requisite young sacrificial victim. The power serpent in the bundle on her back now seems to be a rattlesnake. Like in Borgia, Tepeyollotl is again a full-scale jaguar without human features. The bluish item above its nose is curiously much the same as that in the Borbonicus patron panel—and disturbingly, the jaguar has five claws on each of its forepaws. Your guess is as good as mine as to what these details might signify.

The extra items are also very similar to some in the Borgia trecena: the shield and arrow bundle and the mysterious beaded loop with bow. The pot harks back to the elegant container in Borgia but now has a fanged face, perhaps relating to the pot in Borbonicus with the skulls for feet.

#

I can only point out these odd details—not explain them. Let’s leave interpretations to those who would use these images for divination (as they were originally intended). Apropos the doctrinal disagreement about secondary patrons mentioned at the beginning of this discussion, we’ve now checked out these six examples of the Deer trecena, and the vote is three for Quetzalcoatl, two for Tlazolteotl, and one abstention. Why don’t we just call it a tie and let would-be fortune-tellers pick and choose their auguries?

Another outcome of comparing these six tonalamatls is that I no longer feel like a heretic for the unique layout of my old Tonalamatl Balthazar. So what if my tonalli range around three sides? There’s nothing sacrosanct about dividing up the thirteen tonalli or the direction they run. I frankly think my modern trecenas are as authoritative and veracious as any of those ancient tonalamatls—and at least as beautiful.

UPCOMING ATTRACTION

The next trecena will be that of Flower with its fun-loving patron Huehuecoyotl (the Old Coyote) and a couple other deities of celebration. Stay tuned!

#