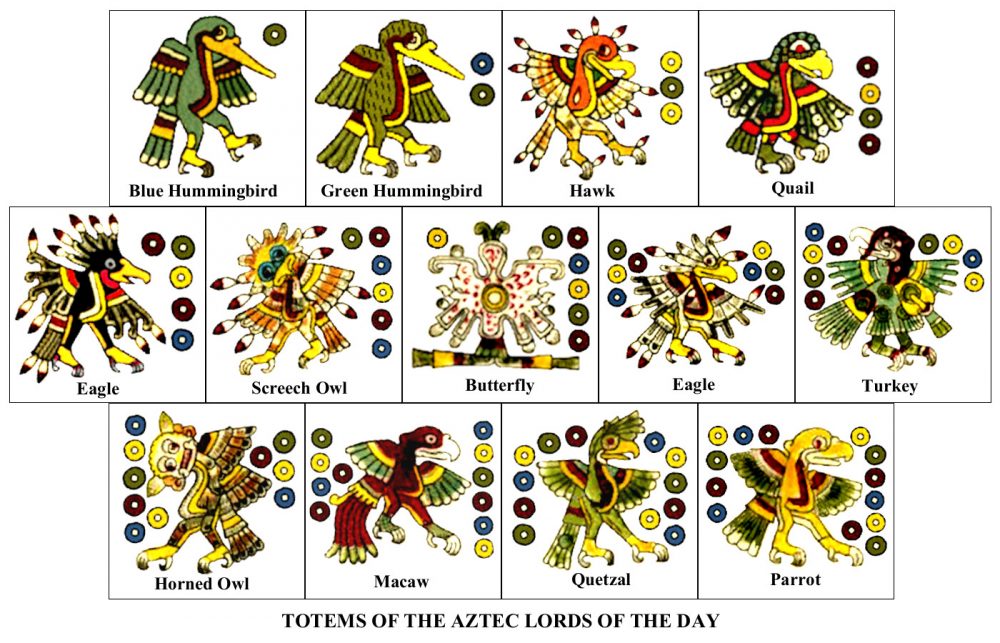

In Codices Borgia and Vaticanus, the 13-day ceremonial week (trecena) is laid out in a complex day-count (tonalpohualli) with a panel presenting its divine ruler(s) or patron(s). In Codex Borbonicus and Tonalamatl Aubin, both the Lords of the Day (with their totem birds) and Lords of the Night are included but aren’t very easy to differentiate/identify. In its spreadsheet-format calendar, Codex Cospi also inserts the Lords of the Night in equally sketchy heads and symbols.

Meanwhile, Codices Telleriano-Remensis and Rios (an Italian copy of the former) accompany the trecena day-counts with the nine Lords of the Night. They appear in a super-cycle sequence that takes several 260-day ceremonial years (calendar rounds) to complete. In that sequence, each one presides over the whole night, and in the same sequence, one presides over each of the nine hours of the night. (Point of curious information: The Aztecs counted 13 daylight hours and 9 hours of darkness, so the actual length of an hour varied proportionately and by season.)

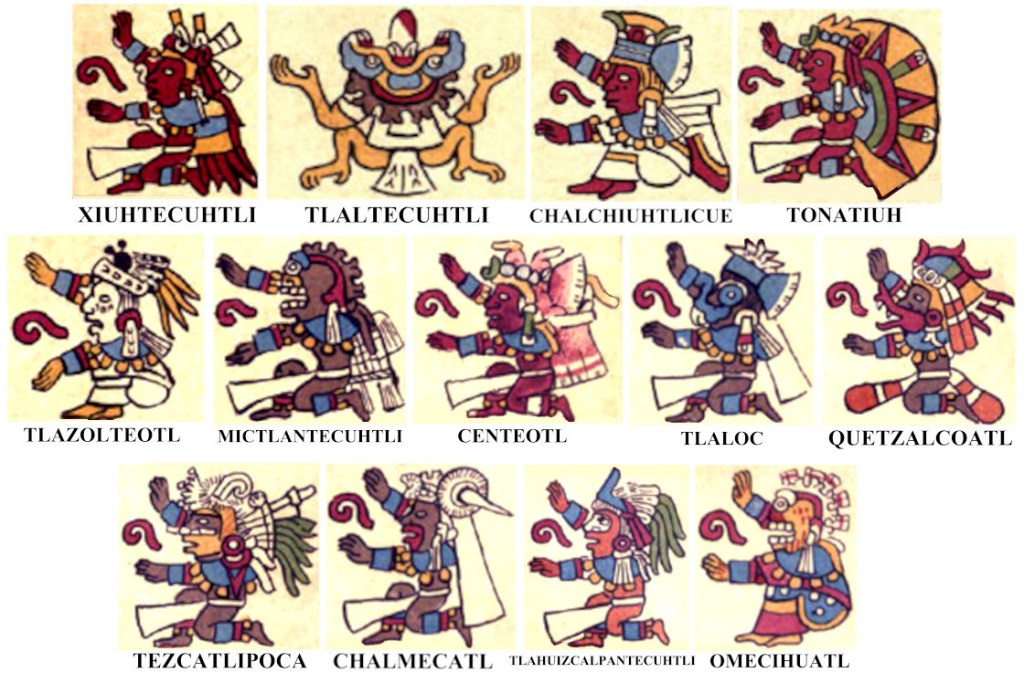

In the T-R and Rios codices, the Night Lords are sloppily drawn, even slap-dash, though with consistent, if careless, motifs. I’ve chosen to refine their iconographic images, giving them more realistic faces like in Codices Fejervary-Mayer and/or Laud:

1st Lord—Xiuhtecuhtli—Lord of the Turquoise/Fire. The peaked headdress and red ribbon are standard emblems of this deity who represents the center of time and space.

2nd Lord—Itztli—Obsidian (Knife). I don’t know what the standard black markings on his face might signify, but those things in his “hat” are sacrificial knives.

3rd Lord—Pilzintecuhtli—Young Lord, God of the planet Mercury. He’s also a “sun-lord” as shown by the sun in his headdress.

4th Lord—Centeotl—God of Maize. Check out the indicative cobs of maize in his headdress.

5th Lord—Mictlantecuhtli—Lord of the Land of the Dead. This human image is most unusual for a face of death; usually he’s a skull on a skeleton. (See my Icon #10.)

6th Lord—Chalchiuhtlicue—Jade Skirt, Goddess of Flowing Water. (See my Icon #2.) Females could also be Lords since tecuhtli actually means more like “ruler.” (She may be the ancestral Great Goddess from ancient Teotihuacan.)

7th Lord—Tlazolteotl—Goddess of Filth (literally). Her mouth is black from eating people’s filth/sins. In her headdress are spindles of spun cotton and tassels of unspun, showing that she’s also the goddess of weaving.

8th Lord—Tepeyollotl—Heart of the Mountain, God of Caves/Volcanos/Earthquakes and Jaguar of the Night. I can’t explain his tri-color face in these calendars. (See my Icon #17.)

9th Lord—Tlaloc—God of Storms. His goggle-eyed, long-toothed visage is emblematic in most codex contexts. (See my Icon #20.)

For the 2nd Lord of the Night, some sources name Tezcatlipoca, the Smoking Mirror (See my Icon #19) in place of Itztli, but that’s based solely on his image on the Night Lord page in Codex Borgia (p. 14) showing them in full figure. In fact, Itztli is a principal nagual (manifestation) of the “Black One,” who’s supposedly invisible. The Borgia figure has a sacrificial knife as one of his feet, so it clearly intends to be Itztli.

#

Recently my knowledgeable Mayanist friend mentioned that the unusual 52-count of solar years (“Aztec Century”) in Codex Borbonicus accompanies each year with a Night Lord, though in a strange sequence/cycle unlike that for the day-count, and he explained the basis for it. I’d never paid that year-count much attention, and his explanation was an eye-opener. The 52- count of solar years (not of 260-day ceremonial years!) in that codex appears on two pages (pp. 21 & 22), each with 26 years in their ritual count in a system related to the day-count.

Four of the days in the 20-day month of the solar calendar are (for very complicated, but comprehensible reasons) are chosen as “year-bearers:” Rabbit, Reed, Flint, and House. In that order, they’re counted in cycles of 13, i.e. One Rabbit, Two Reed, Three Flint, Four House, Five Rabbit, Six Reed, etc. Like the trecena process in the ceremonial day-count, this produces four trecenas of years, which I call “trecades.”

Curiously, the century cycle is structured just like a cross-counted deck of playing cards with Rabbit = Clubs, Reed = Diamonds, Flint = Hearts (appropriately), and House = Spades. In this correspondence, the numbers work as well: 1 = Ace, 11 = Jack, 12 = Queen, and 13=King. By the way, in the following image of the first half of the cycle, the central panel portrays the goddess of the night Oxomoco (on the left, strewing stars like seeds) and the god of the day Cipactonal (on the right, burning incense).

This first page of the count lays out the One Rabbit and One Reed sequences, each with a Night Lord as principle divine patron of that year:

Clockwise from lower left

One Rabbit—Mictlantecuhtli

Two Reed—Piltzintecuhtli

Three Flint—Tlaloc

Four House—Tlazolteotl

Five Rabbit—Centeotl

Six Reed—Xiuhtecuhtli

Seven Flint—Tepeyollotl

Eight House—Mictlantecuhtli

Nine Rabbit—Piltzintecuhtli

Ten Reed—Tlaloc

Eleven Flint—Chalchiuhtlicue

Twelve House—Centeotl

Thirteen Rabbit—Xiuhtecuhtli

Clockwise from upper right

One Reed—Tepeyollotl

Two Flint—Mictlantecuhtli

Three House—Piltzintecuhtli

Four Rabbit—Tlaloc

Five Reed—Chalchiuhtlicue

Six Flint—Centeotl

Seven House—Piltzintecuhtli

Eight Rabbit—Tepeyollotl

Nine Reed—Mictlantecuhtli

Ten Flint—Itztli

Eleven House—Tlaloc

Twelve Rabbit—Chalchiuhtlicue

Thirteen Reed—Centeotl

The little glyphs of these Night Lords are fairly consistent, though sometimes hard to recognize. Note the three stylized place symbols (for Seven Flint, One Reed, and Eight Rabbit), which represent a mountain with a heart emblem (i.e., Tepeyollotl, Heart of the Mountain). Also note that 10 Flint is accompanied by a stylized sacrificial knife (i.e., Itztli).

The busts of the other Lords are mostly recognizable by their regalia, except for confusing variations in the four differing instances of Pilzintecuhtli (Two Reed, Nine Rabbit, Three House, and Seven House) and the two of Xiuhtecuhtli (Six Reed and Thirteen Rabbit). Further confusion is caused by the fact that Xiuhtecuhtli in Six Reed and Pilzintecuhtli in Seven House are both singing/speaking. We just have to learn to live with these inconsistencies.

The second half of the count occurs on p. 22, presenting the One Flint and One House sequences, each year again with its patron Night Lord in an entirely different selection. You can make your own list of patrons. The system for assigning annual Night Lord patrons is another tie-in with the ceremonial day-count. Each year (like One Rabbit, Two Reed, etc.) is paired with the Night Lord for the corresponding numbered day in its trecena (Mictlantecuhtli, Pilzintecuhtli, etc.)

Because of the nine-cycle of Night Lords in the tonalpohualli and the 52 years in the century, the year patrons don’t work out evenly or in a logical pattern. Some appear 6 times, some 5. Of course, the nine-cycle also doesn’t quite fit in the tonalpohualli itself (260 / 9 = 28.89), and it can only accomplish a full cycle in 9 years (28.89 X 9 = 260). That means that the first ceremonial year ends with Tepeyollotl on Thirteen Flower, and the second year starts with Tlaloc on one Crocodile. The ninth year will finally end with Tlaloc on Thirteen Flower.

Consequently, the sequence of Night Lords from which the annual patrons are selected exists only in the first calendar round of the standard tonalpohualli. In the next eight rounds, the days all have different Lords of the Night as patrons. Does this mean that the years in the next eight centuries had different patrons too? Then the tenth century returns to the first distribution. This odd cycle means that the Aztecs may have counted a “nonennium” of 468 years (9 X 52 = 468), or perhaps the repeating tenth century constituted a true millennium of 520 years.

Perhaps they did—I’ve seen somewhere that they considered the previous four Suns/eras (Four Jaguar, Four Wind, Four Rain, and Four Water) to have lasted 520 years. In that case, since we don’t know exactly when the Fifth Sun (Four Earthquake) began, it probably ended officially at some point in the 16th or 17th Gregorian century.

I have no difficulty personally in construing the Fifth Sun as starting on or around 1000 CE during the Toltec dominance and ending in 1519 CE when the invaders obliterated the Aztec empire. If so, a Sixth Sun (which for obvious symbolic reasons I would choose to call Four Death) may have begun in 1520—to end in or around 2040 CE. In another 16 years, we may move into a Seventh Sun (which I would hopefully call Four Flower). Once again, we could be looking at a Mesoamerican cycle ending, this time as an Aztec prophecy.

###