When they founded Tenochtitlan c. 1325 CE, the Aztec barbarians adopted the traditional Mesoamerican temporal and spatial concepts of ceremonial calendar and cardinal directions.

The 260-day Aztec Turquoise Year or tonalpohualli (ceremonial count of days) is based on 20 numbered sets of 13 called trecenas, through which the 20 named days of the solar month are counted cyclically. That’s about as clearly as I can describe it. Some of the few surviving codices (ancient documents) include individual pages of the trecenas with their patron deities.

Some codices also have pages with the 260 days laid out in spreadsheet fashion with five rows of 52 columns in four sets of 13, Here’s a sample section from Codex Vaticanus laying out the first set of 13 columns (trecenas 1, 5, 9, 13 and 17):

First Section of Spreadsheet Calendar, Codex Vaticanus

One reads left to right starting with day One Crocodile on the bottom row at lower left; after counting the 52 days in that row, we come back to the second row from the bottom beginning with Reed. Repeating that process, the count returns to the first column to resume with the days One Snake, One Earthquake, and One Water. The blocks of four columns of five days repeat 13 times—only in varying internal sequences—symbolizing the four cardinal directions:

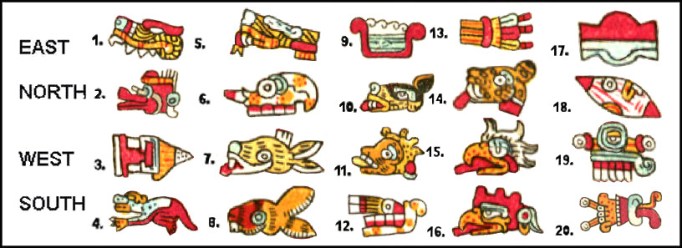

Vaticanus Day-Signs Corresponding to Cardinal Directions

Numbered per their position in the 20-day “month,” these are East: Crocodile, Snake, Water, Reed, Earthquake; North: Wind, Death, Dog, Jaguar, Flint; West: House, Deer, Monkey, Eagle, Rain; South: Lizard, Rabbit, Grass, Vulture, and Flower.

These four cardinal directions are also characterized by colors: East—red; North—black; West—white; and South—blue. This color scheme correlates to the emblematic colors of the Aztec gods of the directions: Xipe Totec, God of the East—the Red Tezcatlipoca; Tezcatlipoca, God of the North—the Black Tezcatlipoca; Quetzalcoatl, God of the West—the White Tezcatlipoca; and Huitzilopochtli, God of the South—the Blue Tezcatlipoca.

The traditional spatial matrix inherited by the Aztecs also included a fifth direction—the Center—which they saw as ruled by Xiuhtecuhtli, the Lord of Fire/Turquoise.

XIUHTECUHTLI, God of the Center

With the Mexica’s tribal War God Huitzilopochtli ruling the South, this is emphatically the Aztec empire’s imperial vision of the divine quartet/quintet. Wondering what earlier deity may have ruled the South before, I looked at p. 1 of Codex Fejervary-Mayer, a document thought to have originated in the Veracruz region. It lays out the directions with pairs of patrons, totemic trees, and birds. However here, it’s Tezcatlipoca dominating the Center. (Apologies for the scruffy image, but I’ve got neither time nor energy to “re-create” it.)

The Five Directions, Codex Fejervary-Mayer, p. 1

The orientation of the directions is a bit different than our common Eurocentric model, rotated one notch counterclockwise. Here East is at the top, West at the bottom; South is on the right, North on the left. Besides the totemic birds and trees, the busy diagram includes much calendrical symbolism, including the days of the directions, year-bearers, and what-not.

By the way, the South tree is a “sacred” Theobroma (Food of the Gods) cacao tree with its chocolate pods. The totem on the North is a spiky ceiba tree (Kapok) which the Maya saw as the great tree at the center of the world—connecting the Underworld and the Sky World (heavens), its trunk representing the world of humans, animals, etc.

The pairs of patron deities in each lobe include only two of our divine quartet of Tezcatlipocas. In the top East lobe, on the right stands Xipe Totec, our Red Tezcatlipoca, with his Flint headdress, and I’d bet his companion is the sun god Tonatiuh, god of the Fifth Sun. In the left North lobe, the upper deity is a simple version of our Black Tezcatlipoca, and the lower one looks like the mighty Tlaloc, God of Storms. The rest of the patrons are different.

The South lobe on the right tells us who must have ruled that direction before the Aztecs inserted their Huitzilopochtli: the upper Mictlantecuhtli, Lord of the Land of the Dead, and the lower Centeotl, God of Maize. The Aztecs gave them both the boot… In addition, the West lobe on the bottom holds no White Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, showing instead a surprising pair of patrons from pre-Aztec mythology. On the right (upside down) is Chalchiuhtlicue, the Jade Skirt, Goddess of Water, and on the left Tlazolteotl, Goddess of Filth, a major mother deity.

The reputedly misogynist Aztecs seem to have impeached these two great goddesses to install the famous Maya/Teotihuacan/Toltec Plumed Serpent as their deity of the West, as the White Tezcatlipoca. Speaking of misogyny, in another religious coup, the new empire tried to depose the Goddess of the Moon (Ixchel to the Maya and Metztli in Teotihuacan) from her traditional role as patron of the calendar’s Death Trecena and then made their own Tecciztecatl into the God of the Moon. (Metztli can still be seen in the calendar in Codex Telleriano-Remensis.)

The Aztecs were also conservative, if not reactionary, in other ways, like in celebrating their culture as the culmination of the “golden” ages of Teotihuacan and the Toltecs. Witness their great cult of Quetzalcoatl and abject “idolatry” of Tezcatlipoca, also inherited from the Toltecs. Since time immemorial, he and Quetzalcoatl were seen as each other’s twin and nemesis, and in their roster of the gods of the directions, the Aztecs enshrined that primordial conflict. That they apparently replaced the Smoking Mirror with Xiuhtecuhtli as God of the Center is surprising, and it’s even more so that they didn’t make Huitzilopochtli Center and give someone else South. But winners always get to write their own version of history—and religion.

###