The seventeenth trecena (13-day “week”) of the Aztec Tonalpohualli (ceremonial count of days) is called Water for its first numbered day, which is coincidentally the 9th day of the veintena (20-day “month”). In Nahuatl, Water is Atl. It was known as Muluk (Water) in Yucatec Maya and Toj (Rain or “Thunderpain”) in Quiché Maya.

The Aztecs saw the day Water, typically shown as a container spilling water, as connected with the flow/passage through life and time as well as purification and the accumulation of resources and potentials. It’s associated anatomically with the back of the head/hair. The divine patron of the day is Xiuhtecuhtli, the Lord of Fire/Turquoise, who’s a patron of the Snake trecena.

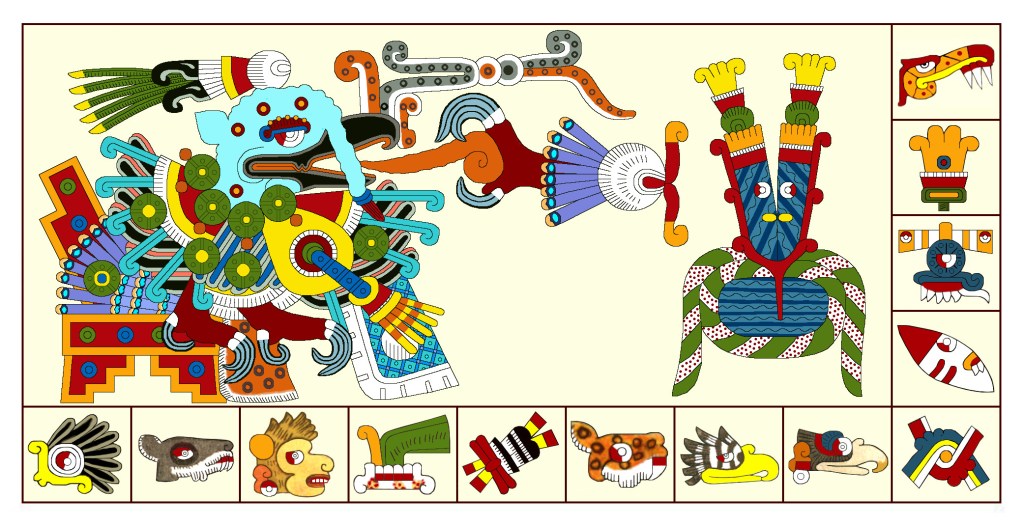

PATRON DEITY RULING THE WATER TRECENA

Chalchiuhtotolin (see Icon #3), the Jade (or Jeweled) Turkey, is another nagual (manifestation) of Tezcatlipoca (see Lizard trecena). As the magnificent patron of his Jaguar Warriors of the Night and of military power and glory, it cleanses them of contamination, absolves them of guilt, and overcomes their fates. Appropriately it’s the patron of the day Flint, the sacrificial knife.

Though symbolic of sustenance and abundance, Chalchiuhtotolin is also associated with disease and pestilence, a creature of death and decay, regeneration and transformation. Chalchiuhtotolin is also linked to the earth’s fertility, agricultural cycles, and the natural order of life and death. Appeasing Chalchiuhtotolin was believed to ensure a smooth transition for the deceased into the afterlife and promote fertility and abundance in the earthly realm.

AUGURIES OF THE WATER TRECENA

By Marguerite Paquin, author of “Manual for the Soul: A Guide to the Energies of Life: How Sacred Mesoamerican Calendrics Reveal Patterns of Destiny”

https://whitepuppress.ca/manual-for-the-soul/

Trecena theme: Generative Vitality, Purification. This life-giving time frame has a generative “firewater” aspect to its energy, representative of the original creation forces that sparked life itself. There is a strong sense of abundance associated with these forces, but these energies can also be “electrical” in the sense that they can “spark” important events, often associated with stimulation and cleansing. Like water itself, this period holds the potential to create pathways that can shape or change the world. This trecena has also been associated with omens.

Further to how these energies connect with world events, see the Maya Count of Days Horoscope blog at whitepuppress.ca/horoscope/ Look for the Muluk trecena.

THE 13 NUMBERED DAYS IN THE WATER TRECENA

The Aztec Tonalpohualli, like the ancestral Maya calendar, is counted through the sequence of 20 named days of the agricultural “month” (veintena), of which there are 18 in the solar year. Starting with 1 Water, it continues the trecena with: 2 Dog, 3 Monkey, 4 Grass, 5 Reed, 6 Jaguar, 7 Eagle, 8 Vulture, 9 Earthquake, 10 Flint, 11 Rain, 12 Flower, and 13 Crocodile.

There’s one special day in the Water trecena:

One Water (in Nahuatl Ce Atl) –the day-name of Chalchiuhtlicue, the Jade Skirt, the patron of the Reed trecena. In the Florentine Codex, it’s noted as a feast day for those involved in the water industries, but I can only speculate what those were.

THE TONALAMATL (BOOK OF DAYS)

Several of the surviving so-called Aztec codices (some originating from other cultures like the Mixtec) have Tonalamatl sections laying out the trecenas of the Tonalpohualli on separate pages. In Codex Borbonicus and Tonalamatl Aubin, the first two pages are missing; Codex Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Rios are each lacking various pages (fortunately not the same ones); and in Codex Borgia and Codex Vaticanus all 20 pages are extant. (The Tonalpohualli is also presented in a spread-sheet fashion in Codex Borgia, Codex Vaticanus, and Codex Cospi, but that format apparently serves other purposes.)

TONALAMATL BALTHAZAR

As described in my earlier blog The Aztec Calendar – My Obsession, some thirty years ago—on the basis of very limited ethnographic information and iconographic models —I presumed to create my own version of a Tonalamatl, publishing it in 1993 as Celebrate Native America!

Yet again, I knew nothing about traditional images of the Jade Turkey and simply played with a Nuttall-style guy in a turkey-suit, the dominant green color reflecting the “jade.” Only many years later did I discover true details of this deity’s mythology—and the unusual type of turkey it references. The following patron panels will explain a lot of little-known turkey-trivia.

#

TONALAMATL BORGIA (re-created by Richard Balthazar from Codex Borgia)

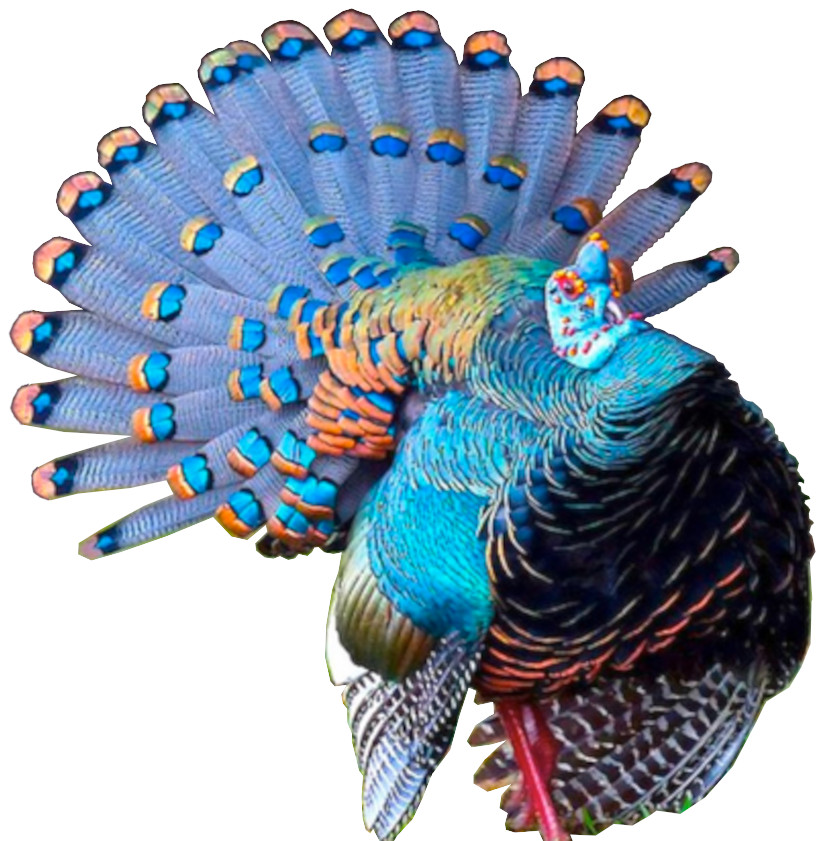

Besides the “Jade Turkey,” Chalchiuhtotolin is also called the “Jeweled Turkey”—referring to Meleagris ocellata, an endangered species native to Yucatan, Belize, and Guatemala and named for “eyes” on its imposing fan of tail feathers. With stunning blue-to-purple-to-green plumage, this rara avis is a distant cry from the standard “Thanksgiving” turkey (Meleagris gallopavo).

Surely known personally to the Maya but likely only mythically in Mexico, this rare bird as patron of the Water trecena shows its ancient heritage. The peoples of Mexico found significant sustenance and abundance in its drabber but larger cousin, the Wild Turkey, ancestor of our even bigger domestic turkey. But they “idolized” a mythical jeweled fowl that could be called the “Turquoise Turkey” (Xiuhtotolin). Coincidentally and appropriately, that could also mean “Fire Turkey.” Since the bodies of ocellata were many shades of iridescent emerald-green, simply “Jade Turkey” is its best label.

The color palettes of codex artists included very few shades of blue which differed over time and area. The Maya had a famous blue of unknown source, and the Mexicans later achieved a generous blue like in Codex Borbonicus. In Codex Borgia, most intended blues have degraded into shades of grey (as have any hues of green into brownish-golds). Codex Laud and Codex Fejervary-Mayer use a dark greenish or slate tone for blues and/or greens, with other colors fairly vivid. In Vaticanus b (predominantly cochineal red and brownish gold), they managed some subdued blues and greens almost like highlights. But a true turquoise was way out of an artist’s reach, not to mention any shade of purple.

That made it essentially impossible to depict Chalchiuhtotolin in all its iridescence. The Jade Turkey mostly appears in codices with a red head and brownish feathers, like their common farmyard gobblers. But in Codex Borgia, the mythical bird has a stylized ocellated fantail (now become blacks and greys) and brownish-gold medallions for the glowing green on its breast.

I chose to color our divine bird naturalistically—i.e., just about as supernaturally as it gets, that turquoise head and purplish tail. I wonder about that suspicious ear on the back of its head. Turkeys don’t have ears like mammals. And what’s that big tassel-thing on its breast? Well, recently I learned about turkeys’ beards. When toms (and some hens) get on in years, they can grow a long spike of feathers straight out from their breasts. That ornament and a many-eyed fan makes a formidable fowl of military majesty, a great patron for the Jaguar Warriors of the Night.

Chalchiuhtotolin seriously dominates this patron panel, especially with all that stuff the deity is evidently exhaling. The upper curlicues we now know are grey smoke and orangish fire, which makes sense for a “Fire Turkey,” a fire-breathing warrior-bird, but the curly thing caught in the disembodied claw sure doesn’t. Hanging right there in the center of the panel, it must be primally important, maybe a hieroglyphic message or utterance by the deity. Or it may be simply an abstraction for the wide range of calls, cackles, and gobbles that turkeys make.

Meanwhile, the surreal item on the right invites more interpretation. No doubt, it involves two spotted serpent tails encircling a body of water. However, the snakes’ heads lift up between knobbed sides like spouts of water (with eyes and mouths!) and top off with big flowers. The motif of a snake containing a volume of water is also seen in ancient Maya iconography—and this is after all, the Water trecena. Gathering and containing water, the essence of accumulation, provides the Jade Turkey’s abundance. So, here there be water-serpents.

Which raises a neat linguistic point: At a recent lecture, I learned that in Aztec iconography many of the images are actually hieroglyphs, pictorially and/or phonetically significant. For instance, a pot or jug with water splashing out of it can be read as a word in Nahuatl. The first syllable of their word for pot/jug/jar is co-,and their word for ‘water’ is atl. So, co-atl spells ‘snake.’ This item is in fact a decorative and emphatic hieroglyph for ‘water-serpent.’

This page for the Water trecena I consider perhaps the most glorious in the Tonalamatl Borgia, not only for its intended colors but for its surrealism. Even without the appended material and fancy water-serpent glyph, this image of Chalchiuhtotolin is inarguably the apotheosis of the turkey. (Worshipping it is a whole lot kinder—and respectful—than cooking it for dinner.)

#

TONALAMATL YOAL (compiled and re-created by Richard Balthazar on the basis of

Codex Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Rios)

This series of compiled trecena pages that I call Tonalamatl Yoal opts for a far less naturalistic image of an ocellata with the brown feathers and red head of the common gallopavo. However, there’s no clear reason for its yellow feet or the epaulets on its wings. The “jeweled” aspect of divine Chalchiuhtotolin is shown by the jade pendants on its plumage and probably the turquoise collar, but I can’t explain the apron of quetzal plumes that almost hides its jaguar-pelt “pants.” Those may indicate its nagual connection to Tezcatlipoca as does the variant smoking mirror in its headdress—a logical source of the flame and smoke seen before as the breath of the Borgia bird. Apart from the shape of the head, this heavily stylized portrayal of the deity doesn’t look much like a turkey, especially that tail, but it’s certainly an elegant fowl.

Instead of any water-serpent reference, on the right side is another figure of a human worshipper performing a ritual blood sacrifice like the guy in the Jaguar trecena. That one (with the same bound hairdo but no headdress) pierces his tongue with a pointed stick. This one jabs himself in the ear with a sharpened flowering shinbone—oddly emblematic of Quetzalcoatl, as are the two ornamental conch shells. The devout fellow also offers the deity a fancy incense bag.

Though it shares the stage here with a worshipper, Chalchiuhtotolin is clearly the sole patron of this Water trecena. As before with the tongue-piercer with Quetzalcoatl in the Jaguar trecena, this ear-stabber may merely indicate the preferred method of blood-sacrifice to the Jade Turkey. I haven’t studied the matter, but I suspect the Aztecs had prescribed rituals of phlebotomy for specific deities, including slicing other body-parts, flagellation, flaying, and eye-poking (like in the Flower trecena). It was obviously a great culture for masochists.

#

OTHER TONALAMATLS

It’s no surprise that the turkey in the Tonalamatl Aubin patron panel can scarcely be called elegant. Looking more like a limp rubber chicken, it’s nevertheless supposed to be the divine Chalchiuhtotolin as shown by a half-hearted smoking mirror in its headdress. While the little guy pretends to stab his ear, three awkward conch shells seem to relate to familiar water-serpent symbols. Apparently, the Aubin artist(s) held Chalchiuhtotolin in only minimal awe.

#

The Jade Turkey in the Codex Borbonicus patron panel, however, is rather awesome with an ornate smoking mirror and Tezcatlipoca’s beribboned circular pendant. Its anthropomorphic nature (a guy in a turkey suit) nicely justifies my own even more awesome interpretation in Tonalamatl Balthazar. In the crowd of ritual paraphernalia, I wonder about that central green pulque pot; is he drinking from it or vomiting into it? The little guy on the right of it with the colorful snake is again stabbing an ear and carrying an incense bag and a conch shell. The co-atl glyph in the lower right corner must refer to both the Water trecena and water-serpent, and fire and smoke issue from a burning temple. The cluster of symbols (including a familiar scorpion) might be elements of some hieroglyphic sentence.

#

In Codex Vaticanus, the Jade Turkey distinctly reflects the Borgia image, some blue in the fantail with stylized “eyes, a geometrically abstracted wing, and a small beard on its breast. One gets the feeling that the artist probably intended to paint the white spaces in ocellata colors but didn’t get around to it. (I’m tempted to finish the job but have other fish to fry right now.)

The cluster of motifs above its head also reflects the Borgia image: plumes of smoke and fire and stylized water-serpent heads (without faces) capped with flowers. In this instance, the red “walls” of the waterspouts are evidently penitential thorns, explaining the knobbed structures in Borgia. Most interesting is the curly exhalation with stars attached grasped again in a disembodied claw; it suggests darkness or night, possibly explaining the enigmatic brown Borgia detail. The deity was sometimes called the “Precious Night Turkey”—maybe since Tezcatlipoca was the god of the night or for its patronage of the Jaguar Warriors of the Night.

This Vaticanus Chalchiuhtotolin is exceptional, both in stylized detail and in being the sole image in the patron panel. Displaying no specific emblem of Tezcatlipoca, this Jade Turkey seems (like the Borgia bird) to proclaim its independent divinity.

#

I’m impressed by the virtuosity of the Vaticanus artist(s) in stylizing certain animals like the dog (discussed in the previous Vulture trecena) and this Jade Turkey. Elsewhere in the codex they have twice drawn turkeys in the context of their patronage of the day Flint, on pp. 29 and 93:

From different sections of the codex but in similar poses (and both sporting impressive beards), these two gobblers may well have been drawn by different artists in slightly different personal styles. The one on the left is clearly a common variety tom, but apart from the necessarily red head, the one on the right looks to be an authentic ocellata with the eyes on its fantail and more intricate plumage. Perhaps the magnificent trecena patron image was created by yet a third artist, someone more fluent in religious symbolism.

###

You can view all the calendar pages I’ve completed up to this point in the Tonalamatl gallery.