The fifteenth trecena (13-day “week”) of the Aztec Tonalpohualli (ceremonial count of days) is called House for its first numbered day, which is the 3rd day of the veintena (20-day “month”). In Nahuatl, House is Calli, and it’s known as Ak’b’al in Yucatec Maya and Ak’ab’al in Quiché.

My early research told me that for the Aztecs, the day House represents nobility and intelligence. Its sign is a stylized house (calli) or temple (teocalli); educational centers were a telpochcalli, and priests were trained in the calmecac. My great Maya advisor, Dr. Paquin, tells me that they considered Ak’b’al to represent a sanctuary or place of retreat, a place for contemplation, study, and creative exploration. She adds that the day also represents the night and darkness, i.e., the magical nocturnal realm. How much of that made it into Aztec symbology, one wonders, but they associated the day House anatomically with the right eye. The patron of the day is the Heart of the Mountain, Tepeyollotl (See Icon #17), god of caves (speaking of sanctuary/retreat), who appeared in the Deer trecena as Jaguar of the Night, another rather appropriate detail.

PATRON DEITY RULING THE HOUSE TRECENA

The ruler of the House trecena is the frankly frightening Itzpapalotl (the Obsidian Butterfly), the ancestral goddess of the stars (Milky Way), lady of mystery and death—but perversely, also of beauty and fertility. (See Icon #8.) Patron of the day Cozcacuauhtli (Vulture), she’s a fearsome warrior who rules over the paradise of Tamoanchan for victims of infant mortality. She may be the mother of Mixcoatl, the Cloud Serpent, and is a patron of the dire sisterhood of Cihuateteo (Divine Women), warrior spirits of women who die in childbirth. She’s patron and leader of the Tzitzimime, star demons that come down and devour people during solar eclipses. Like them, Itzpapalotl can be depicted with a skull-face and butterfly or eagle wings, but she can also be a beautiful woman. Below, we’ll see her in all those aspects—and as a surreal nightmare!

AUGURIES OF HOUSE TRECENA

By Marguerite Paquin, author of “Manual for the Soul: A Guide to the Energies of Life: How Sacred Mesoamerican Calendrics Reveal Patterns of Destiny”

https://whitepuppress.ca/manual-for-the-soul/

The theme of the House trecena is Darkness, Mystery, Trauma, and Challenge. Overseen by a deity who appears to represent the struggles of the soul as it strives to overcome the traumas and tribulations of life, this trecena often places emphasis on events and issues that have significant moral and ethical implications for humanity. Personal sacrifices and “warrior” instincts may be needed to navigate through the challenges of the earthly realm. This is a good period for reflection, assessment, and soul-searching in order to find new ways to move through the darkness and into the light.

Further to how these energies connect with world events, see the Maya Count of Days Horoscope blog at whitepuppress.ca/horoscope/ Look for the Ak’b’al trecena.

THE 13 NUMBERED DAYS IN THE HOUSE TRECENA

The Aztec Tonalpohualli, like the ancestral Maya calendar, is counted through the sequence of 20 named days of the agricultural “month” (veintena), of which there are 18 in the solar year. Starting with the 3rd day of the current veintena, 1 House, it continues: 2 Lizard, 3 Snake, 4 Death, 5 Deer, 6 Rabbit, 7 Water, 8 Dog, 9 Monkey, 10 Grass, 11 Reed, 12 Jaguar, and 13 Eagle.

There’s one special day in the House trecena:

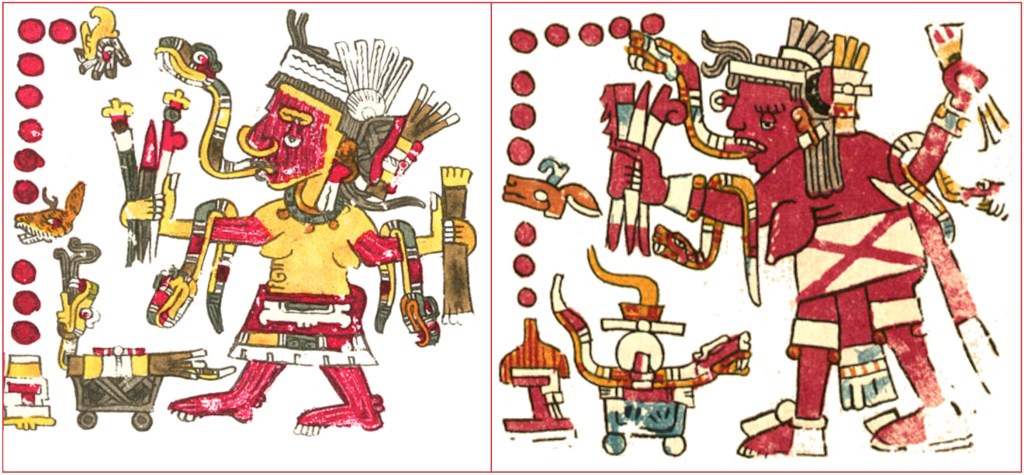

One House (in Nahuatl Ce Calli)—Day-name of one of the five main Cihuateteo (Divine Women), spirits of women who die in childbirth. Except for One Eagle (Ce Cuauhtli), we’ve seen all the others in their respective trecenas: One Deer (Ce Mazatl), One Monkey (Ce Ozomatli), and One Rain (Ce Quiahuitl). The picture below shows a Cihuateotl, One Deer, seen in two codices with clearly very orthodox iconography. They mainly differ in which way the snakes hang from their arms and the patterns on their skirts. The bloody teardrops are emblematic of the Cihuateteo as spirits of the Underworld (Mictlan).

Somewhere I read that One House may be the day-name of Itzpapalotl herself, so that could in truth be a cameo appearance of the goddess in the Flower trecena as a seductive woman. Meanwhile, Tlazolteotl is sometimes called a Cihuateotl, but I’d bet as the celebrity mother-goddess, she’s probably another patron of the five Divine Women.

Lore has it that especially on their name-day nights, the Cihuateteo lurk at crossroads to seduce and murder men or to capture young children—so they can become mothers. Although honored as fallen warriors, they’re sometimes shown with skeletal faces and clawed feet and hands, goddesses of the twilight. Their supernatural chore is to conduct the sun into the underworld at the end of the day—then go out and haunt the crossroads like bogey-mamas.

THE TONALAMATL (BOOK OF DAYS)

Several of the surviving so-called Aztec codices (some originating from other cultures like the Mixtec) have Tonalamatl sections laying out the trecenas of the Tonalpohualli on separate pages. In Codex Borbonicus and Tonalamatl Aubin, the first two pages are missing; Codex Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Rios are each lacking various pages (fortunately not the same ones); and in Codex Borgia and Codex Vaticanus all 20 pages are extant. (The Tonalpohualli is also presented in a spread-sheet fashion in Codex Borgia, Codex Vaticanus, and Codex Cospi, but that format apparently serves other purposes.)

TONALAMATL BALTHAZAR

As described in my earlier blog The Aztec Calendar – My Obsession, some thirty years ago—on the basis of very limited ethnographic information and iconographic models —I presumed to create my own version of a Tonalamatl, publishing it in 1993 as Celebrate Native America!

After trying my best to be authentic in portraying the first fourteen trecena patrons, I indulged in a bit of imagination in this representation of Itzpapalotl, modelled on the Codex Borbonicus image (See below). However, fascinated by her “butterfly” persona, I replaced her Borbonicus bird-wings with those of a tropical butterfly called Armandia Lidderdalei. Please forgive my artistic license. Meanwhile, I cued to her claws in the Borbonicus panel (for which she’s called “the Clawed Butterfly”), though confusing jaguar claws and eagle talons. Noting a reference to her “skeletal face,” I gave her one not unlike that in the following Borgia image.

The result is probably the most gruesomely gorgeous deity I’ve ever drawn. By the way, that’s a sacrificial knife she holds in her left hand/claw. I adapted this image for my coloring-book series Ye Gods! Icons of Aztec Deities (2017-2020), and it was the big hit of the show. In fact, an arts-for-youth group used the black-and-white image as a “cartoon” for their huge rainbow-winged mural of the goddess that can still be seen from the highway. I greatly appreciate the anonymous recognition and welcome anyone’s use of my artwork however they like.

#

TONALAMATL BORGIA (re-created by Richard Balthazar from Codex Borgia)

Aztec Calendar – House trecena – Tonalamatl Borgia

Compared to my Itzpapalotl, this one in Tonalamatl Borgia is merely pretty ghastly, just enough for the leader of the Star Demons (Tzitzimime, singular Tzitzimitl). In the following image I drew from the Post-Conquest Codex Tudela, they look fairly grisly, like a Mesoamerican Medusa.

Honestly, I can think of little else to say about this ghastly Itzpapalotl. The central motifs embody her message of mystery and darkness: her temple of night/stars, an overthrown throne and dead guy, and a fellow blindfolded for some reason. (Sometimes a blindfold indicates weeping—but then why’s he crying?) On the other hand, the tree with a monster-head for roots is an ancient symbol that occurs often in codices, also bleeding, sometimes chopped/wounded by a deity. The motif is inherited from Maya iconography where a crocodile (caiman) head represents the Earth Monster, out of which grows the Tree of Life. The bleeding, monster-rooted tree also appears with Itzpapalotl in her day-Vulture patron panels both in Borgia and Vaticanus.

#

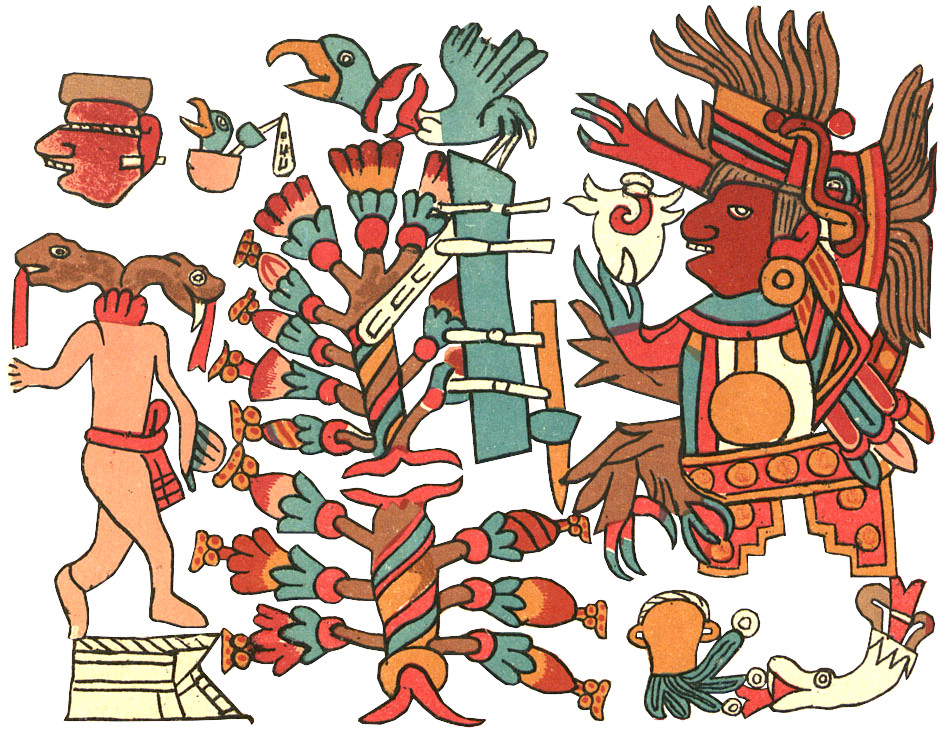

TONALAMATL YOAL (compiled and re-created by Richard Balthazar on the basis of

Codex Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Rios)

Aztec Calendar – House trecena – Tonalamatl Yoal

In both the Telleriano-Remensis and Rios versions, the intricate figure of Itzpapalotl includes her eponymous butterfly, though stylized within an inch of its insect life as a clawed bug with an outrageously unreal head (triple fangs and star-studded antennae!). For my Tonalamatl Yoal, I gave it the elongated and segmented abdomen added in the Rios copy reflecting a simple arc in Telleriano-Remensis, and I made it blue to suggest a psychedelic dragonfly. If you’re going to hallucinate, you might as well go all the way.

As far as claws go, notice that these are distinctly avian as opposed to the jaguar type in Borgia. Relying on her exuberant accessories in Telleriano-Remensis, I merely replaced some shapeless golden baubles on her unusual furry anklets and wristlets with symbolic stars and gave her a skirt, blouse and mantle in an appropriate night pattern borrowed from Borgia’s temple. Maybe we could also call her Itztlicue (Obsidian Skirt).

While the green plumes are standard ceremonial quetzal feathers, the brown ones in headdress and bustle would seem to be those of the Vulture, the day of which she’s the patron. In the course of re-positioning the goddess’s arms, I emphasized her reputedly alluring femininity by exposing her breast in an iconographically acceptable way, but that doesn’t do very much to beautify her sardonic, toothy grin. Overall, Itzpapalotl is one scary mother of mystery and darkness, an impressive Cihuateotl or Tzitzimitl.

Rather than a monster-head, this bleeding tree has a mass of normal roots and so maybe doesn’t refer to the ancestral Maya theme. Its luxurious display of many kinds of stylized fruit and flowers is in no way botanically realistic but tells us this is still a Tree of Life. Its divinatory purport is unclear (mysterious), and why the pretty thing been chopped in half is still unknown (another mystery). Thus it’s a fitting patron-companion for Itzpapalotl.

#

OTHER TONALAMATLS

The panel in Tonalamatl Aubin leaves no doubt that the central blooming, fruited Tree of Life (again chopped in half) is some kind of a secondary patron of the House trecena. This one is bigger than Itzpapalotl, who’s relatively plain, except for many vulture feathers and bird-claws. In Aubin’s typical awkward stylization, I’d be hard-pressed to call her an attractive woman. Her lack of divine ornamentation suggests to me that the artist was way more concerned symbolically with the Tree and other divinatory clues in the trecena panel.

In terms of clues, I’m genuinely puzzled by the white thing she holds, possibly a conch shell, but the wrong shape and of inscrutable significance. The inverted pot of water and snake-head censer are common motifs, but that strange blue bar with bows in the dead center is a profound mystery. Another such bar is held by Chalchiuhtlicue in the Yoal Reed trecena, where I figured it was a blade of some sort. Maybe this one is too, considering the beheaded sacrificial bird…

And considering the decapitated human figure on the left, which must certainly be important for the auguries of this trecena. With the blindfolded head floating above, it easily reflects the impending fate of that blindfolded figure in Borgia. The detail of two serpents “bleeding” out of the guy’s severed neck is particularly striking because I’ve only seen it elsewhere in that famous huge (8.3 ft.) statue of Coatlicue, the Snake Skirt, sometimes reputed to be mother of the gods and mortals. I think that coincidence is mostly stylistic and has little to do with Itzpapalotl.

#

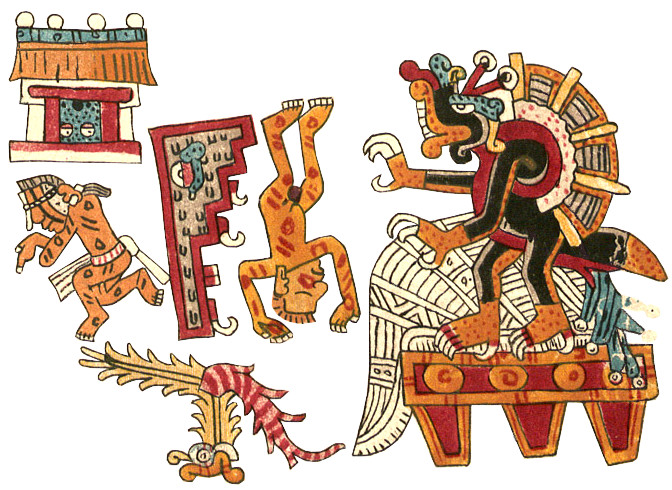

This eagle- (or vulture-) winged figure of Itzpapalotl in Codex Borbonicus was the model for my butterfly version of the goddess, though I ignored those furry wrist- and ankle-bands also seen in Yoal and opted for the skeletal face from Borgia. Here in the upper left, her companion Tree of Life with its severely stylized blossoms is planted in a fancy pot and has again been cut in half. However, rather than bleeding, the base has grown new flowering shoots, whatever that might mean for interpretations.

The dispersed conglom of familiar ritual items includes a beheaded eagle (with blade), incense bag, serpent, etc., as well as the scorpion seen in many Borbonicus patron panels. Most notable is on the lower left where a blindfolded guy lies on a temple of the starry night with two snakes wrapped around his neck, harking directly back to the Aubin image. Perhaps this was to indicate a severed neck without removing the head? In any case, this assemblage fairly well restates all the themes in the Borgia panel—except for the enigmatic overthrown throne.

As in most Borbonicus patron panels there are graphic discrepancies and distortions that I’ve not bothered to remark upon, but in this one, I challenge you to discover the glaring error. Did you find it? Answer: Itzpapalotl’s clawed right hand has a real thumb. The artist may have simply forgotten to color it like a claw. Not that it makes much difference to this elegant image of the goddess of the stars.

#

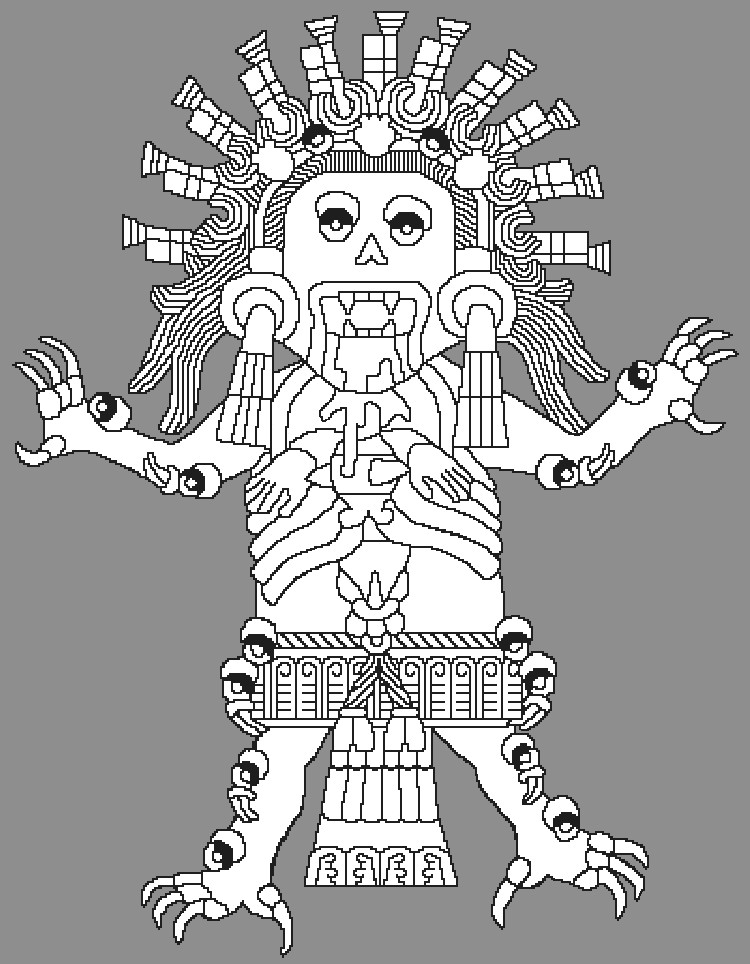

As might be expected, Codex Vaticanus returns to the canonical motifs of Tonalamatl Borgia, simply rearranged and severely re-visioned. The gruesome goddess has here become a surreal monster worthy of a nightmare. It has a crocodilian head (with an insect’s antennae), a lizard-like body with jaguar claws, and a radiating “wing” not at all like that of a bird or butterfly. In fact, it looks more like a dinosaur’s bony crest. This Itzpapalotl gets my vote as the freakiest freak in the in the whole freaking Aztec pantheon.

I can’t imagine what to make of the geometric item behind the throne—or why this “bug-zilla” is urinating so copiously. A similar composite creature portrays Itzpapalotl in a Vaticanus panel as patron of the day Vulture. For a long while, I assumed this thing was the god of monstrosities, Xolotl, and only in reviewing the House trecena panels did I realize my mistake. Now I know.

It’s interesting that this patron panel once again emphasizes the overthrown throne and dead and blindfolded guys—but still doesn’t explain their divinatory significance. And odd how it greatly de-emphasizes the bleeding Tree of Life with its little caiman-head root.

#

These five authentic patron panels show the remarkable orthodoxy of the ceremonial calendar, only differing in small details and degrees of emphasis. In this House trecena, of course, the threatening goddess Itzpapalotl in her wildly varying manifestations is effectively balanced by the positive, hopeful Tree of Life—which leaves the prophetic doors wide open. Meanwhile, considering these demonic images of Itzpapalotl (and Tzitzimime), I can almost understand how the Spanish priests might call the thousands of codices they burned “devil books.”

###

You can view all the calendar pages I’ve completed up to this point in the Tonalamatl gallery.