The eighteenth trecena (13-day “week”) of the Aztec Tonalpohualli (ceremonial count of days) is called Wind for its first numbered day, which is the 2nd day of the veintena (20-day “month”). In Nahuatl, Wind is Ehecatl. It was known as Ik’ (Wind, Breath, Spirit) in Yucatec Maya, and Iq’ (Strong Wind) in Quiché Maya. The patron of the day Wind is Quetzalcoatl (See Icon #14), also patron of the Jaguar Trecena, and the eponymous wind deity Ehecatl (See Icon #5), the Breath of Life and spirit of the Tree of Life itself, is his principal nagual (manifestation).

PATRON DEITY RULING THE WIND TRECENA

Chantico, the Lady of the House (See Icon #4), is the goddess of fire (both in the home/hearth and in the earth), representing the feminine side of life (cooking, eating, and domesticity), the waters of birth, the fire of spirit, fertility and self-sacrifice. Her consort is variously seen as Xiuhtecuhtli, Lord of Fire and patron of the Snake Trecena, or as Tepeyollotl, Heart of the Mountain, the god of volcanoes (See Icon #17) and a patron of the Deer Trecena.

AUGURIES OF THE WIND TRECENA

By Marguerite Paquin, author of “Manual for the Soul: A Guide to the Energies of Life: How Sacred Mesoamerican Calendrics Reveal Patterns of Destiny”

https://whitepuppress.ca/manual-for-the-soul/

Theme: Inspiration, Communication, Necromancy. Traditionally associated with the magical arts, this trecena was used by diviners to select propitious days on which to perform rituals. As Ehecatl represents the divine wind of the spirit, this energy is associated with life, breath, inspiration, and communication, but it can also conjure up storms and bring great change. Under the influence of Chantico, goddess of fire, the Wind trecena can often breathe new life into ideas, and inspire activities aligned with heart-felt communication and the provision of comfort. Use of the magical arts during this period could also help to bring nourishment for the spirit.

Further to how these energies connect with world events, see the Maya Count of Days Horoscope blog at whitepuppress.ca/horoscope/ Look for the Ik’ trecena.

THE 13 NUMBERED DAYS IN THE WIND TRECENA

The Aztec Tonalpohualli, like the ancestral Maya calendar, is counted through the sequence of 20 named days of the agricultural “month” (veintena), of which there are 18 in the solar year. Starting with 1 Wind, it continues the trecena with: 2 House, 3 Lizard, 4 Snake, 5 Death, 6 Deer, 7 Rabbit, 8 Water, 9 Dog, 10 Monkey, 11 Grass, 12 Reed, and 13 Jaguar.

There are two special days in the Wind trecena:

One Wind (in Nahuatl Ce Ehecatl) -traditional day for offerings to be made to Quetzalcoatl. The day appropriately introduces a trecena devoted to sorcery and necromancy.

Nine Dog (in Nahuatl Chicnahui Itzcuintli) – the festival day of magicians, perhaps because the patron of the number Nine was the great Quetzalcoatl himself, and Dog (Xolotl) was a divine magician. Significantly, it is also the birth-day-name of Chantico, the trecena’s patron.

THE TONALAMATL (BOOK OF DAYS)

Several of the surviving so-called Aztec codices (some originating from other cultures like the Mixtec) have Tonalamatl sections laying out the trecenas of the Tonalpohualli on separate pages. In Codex Borbonicus and Tonalamatl Aubin, the first two pages are missing; Codex Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Rios are each lacking various pages (fortunately not the same ones); and in Codex Borgia and Codex Vaticanus all 20 pages are extant. (The Tonalpohualli is also presented in a spread-sheet fashion in Codex Borgia, Codex Vaticanus, and Codex Cospi, but that format apparently serves other purposes.)

TONALAMATL BALTHAZAR

As described in my earlier blog The Aztec Calendar – My Obsession, some thirty years ago—on the basis of very limited ethnographic information and iconographic models —I presumed to create my own version of a Tonalamatl, publishing it in 1993 as Celebrate Native America!

At the time, I didn’t know about Chantico’s importance as a volcano goddess, and my version of her is a quintessentially Codex Nuttall matron tending a stylized hearth-fire. I acknowledged her domestic role by including the weaving spindle—a detail far more appropriate for the goddess Tlazolteotl. The golden bird in her headdress is probably completely out of place, but her jaguar-pelt throne is perfectly appropriate for a goddess. In my Icon #4, I posed Chantico in an ornamental house (temple), which must have been aesthetically successful because that was the one icon banner stolen from the last venue of my YE GODS! show.

#

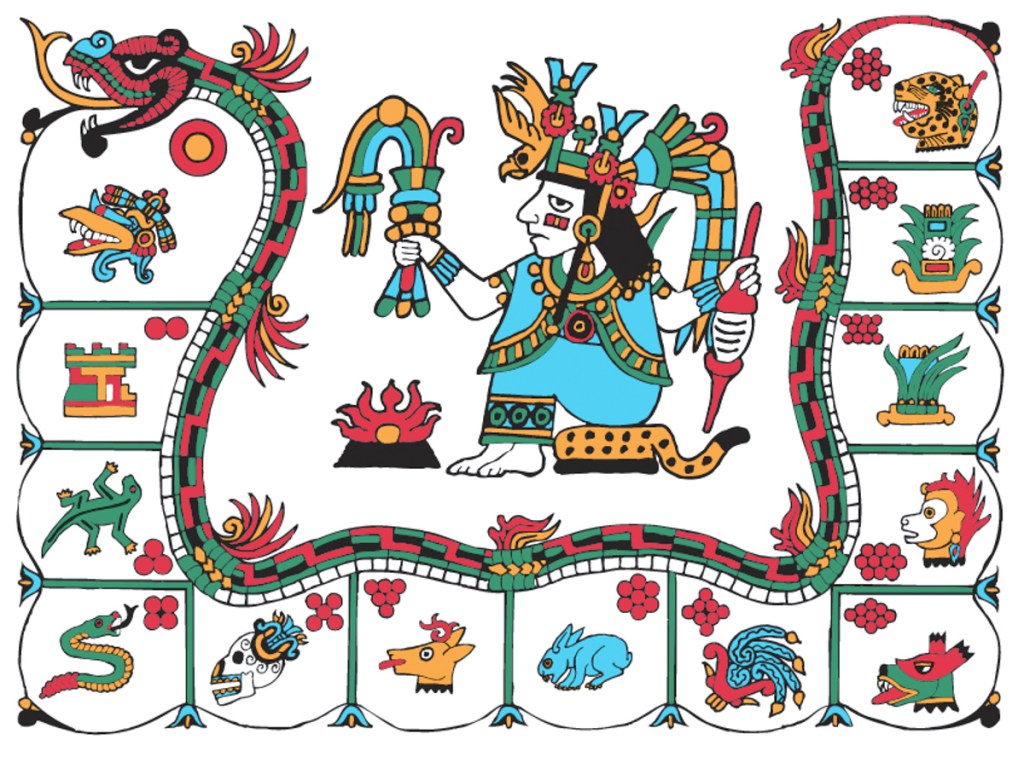

TONALAMATL BORGIA (re-created by Richard Balthazar from Codex Borgia)

The Wind Trecena page in Codex Borgia shows Chantico, sometimes called the Lady of Jewels (Lady of Wealth) as ornately adorned with what may be numerous pearls, but there is little else to identify her. Her nose ornament is a little too generic to serve that purpose, and the enigmatic item (inverted pot?) under her throne doesn’t help either.

More to the point, the three ornate symbols in the center of the panel are glyphs illustrating Chantico’s realms of power. At the top center is a burning temple, metaphorical for fire in the earth (volcano), and in the center is the fire in a hearth/container, both with orangish and gray curlicues of flame and smoke. The large conch at bottom center is probably a reverent gesture or reference to Quetzalcoatl on his special day One Wind.

Much more puzzling than the upside-down pot is the emphatic image on the right side of the panel: an inverted person seemingly falling across a mat or piece of fabric, most definitely not dead—which falling headfirst usually signified—and holding bouquets of vegetation and brightly flowering penitential thorns. Not much to go on here for what this apparently important third of the patron panel might mean. The commentary by Bruce Byland in the Diaz & Rodgers restoration of Codex Borgia doesn’t devote even one syllable to this intriguing detail.

#

TONALAMATL YOAL (compiled and re-created by Richard Balthazar on the basis of

Codex Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Rios)

As usual, in its images of deities for the Wind Trecena, Codex Telleriano-Remensis (and consequently Codex Rios) didn’t skimp on displaying emblems, symbols, and traditional regalia, though the codex-artists didn’t always agree on details. The figures recreated here are based mostly on T/R images with occasional minutiae from Rios. Both figures, of course, had to undergo radical orthopedic surgery for iconographic anatomical awkwardness.

In any case, the paired images make a striking combination. Let’s come back later to the guy on the right and scope out the divine Chantico on the left. Would you look at that headdress! A dark-feathered and be-sea-shelled crest of quetzal plumes pours forth streams of fire and water, creating an elegant atl-tlachinolli (water-fire) glyph—as discussed in the Snake Trecena—usually a symbol of war, but here I think it represents the waters of birth and fire of spirit, attributes of the goddess. Her facial markings and matching ear- and nose-pieces are unusual, but the most disturbing (and unique) detail is her set of Tlaloc-like fangs. How does one fit that sinister motif into Chantico’s official hagiography?

Now we can check out the guy on the right, a figure most unusually in a decorative frame. The little day-sign attached to the back of his head is One Reed—which was used in the Snake Trecena to identify Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli, a nagual of Quetzalcoatl. However, this seems to be Quetzalcoatl himself, probably in honor of his One Wind Festival. Strong evidence is the circular pendant, serpent accessories, black body, and tri-colored face. In fact, Quetzalcoatl was known as One Reed in central Mexico from the ancient Toltec tradition (and in more southerly areas with even older Maya traditions as Nine Wind).

The notations on the T/R and Rios pages (in Spanish and Italian) clearly name the guy Quetzalcoatl but only comment on the frame as his casa de oro. But there’s no way the little falling guy in Borgia can be construed as the great god Quetzalcoatl nor can that decorative mat compare to this deity’s golden house. Whatever Borgia meant by that strange scene may have been used by the T/R artist as an excuse to celebrate Quetzalcoatl as a star of the trecena.

#

OTHER TONALAMATLS

The patron panel in Tonalamatl Aubin merely complicates the situation, presenting an upright little guy with bouquets and without any emblems of Quetzalcoatl—though now in a casa de oro. That motif may bode a deeper significance than even Borgia’s fancy mat. Thinking at first that Yoal’s One Reed glyph might in fact identify Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli, I wondered if maybe the casa de oro could represent the House of the Dawn. That motif also has a connection to Quetzalcoatl as the planet Venus, but I know of no connection between Chantico and dawn. The matter of the little guy remains mysterious.

The hearth fire at the top center is of course symbolic of Chantico, whose plumed headdress is similar to that worn by both figures in the Yoal panel. Her atl-tlachinolli glyph and skull-bustle are repeated here, but the conch over her head seems damaged. The big serpent under her throne must symbolize emphatic sexuality, but I can’t explain the pile of something or other pierced by penitential thorns. The central offering bowl seems rather pitiful, as do the grotesque hands and feet on both figures. Overall, this patron panel isn’t particularly inspiring.

#

On the other hand, the patron panel from Codex Borbonicus is enchantingly ornate. It presents another casa de oro on the left with a common mortal who carries a standard bouquet/weapon and incense bag but again wears the Yoal-style plumed headdress. He does nothing to clarify the mystery. On the right, Chantico sports great bunches of quetzal plumes, another dramatic atl-tlachinolli glyph, and under her throne familiar plumed tassels with seashells. Her unusual sitting posture (hovering above instead of in front of the throne) may be intended to add to her ethereal/divine presence. That nose-clamp looks painful.

The scattered conglom of ritual items raises several questions. Starting in the upper left, what’s the significance of the day-sign One Crocodile (first day of the tonalpohualli)? Or of the standard-design rock/stone. No idea… Top center may be a glyphic hearth-fire. On the lower left seems to be an incense burner, but the leafy swatches beside it are inscrutable. The mounded item just above may be a metaphor for fire in the earth (volcano) and could relate to Aubin’s pile of something or other. But most iconic is the little frilled circle in the center with a star or divine eye in the middle. A traditional symbol of magic or sorcery, it’s the only reference in these patron panels to this trecena’s theme of necromancy.

#

The patron panel from Codex Vaticanus again repeats the inventory of motifs from Borgia, including burning temple, hearth-fire, and conch. But it deepens the mystery of what the little guy represents. Here, he’s a blue figure (possibly a corpse?) in what looks like a box rather than on a mat or in a casa de oro. Still no answers… Apart from her fancy skirt, cape, and body-tattoos, Chantico is pretty plain. Her sitting with feet forward is most unusual, and the confusion of her arms detracts from any divine magnificence.

#

My ancient intuition about Chantico was apparently right on making her a normal, stylish woman. Appropriately, some patron panels give her dramatic emblems I didn’t know about like plumed headdress, fire-water glyph, and power symbols of hearth-fires and volcanoes. While her Borgia portrait is glamorous, her image in Yoal is more ornamental than most calendrical deities in that tonalamatl. Her pairing with the cameo of Quetzalcoatl makes one of the more exquisite Yoal panels, but we can’t take that to mean that he’s also a patron of the trecena. This guy One Reed seems more like a Master of Ceremonies for the magicians’ fiesta week. Maybe the strange little guys in the other tonalamatls are sorcerer-performers.

###

You can view all the calendar pages I’ve completed up to this point in the Tonalamatl gallery.