After wrapping up my little piece about Morning Star mythology in Pre-Columbian America, I turned back to re-creating Aztec codex pages from the calendar and my work on the Vulture trecena (13-day ‘week’), its patron being the god of the Evening Star. The detailed process of pixelating is fairly time-consuming and lends itself to much cogitation and curiosity about the deity at hand. But first some Maya stuff on the Evening Star.

Lady Evening Star of Yaxchilan

No surprise, but my internet search provided precious few hits for Maya Evening Star, the only one being for a Maya queen of Yaxchilan named Great Skull and known as Lady Evening Star. Here’s some fancy ancient royalty gossip: A princess from the formidable city-state Calakmul, she married the ruler of Yaxchilan, Itzamnaaj B’alam III (Shield Jaguar the Great), was the mother of Yaxun B’alam IV (Bird Jaguar) and ruled 742-751 CE until her son’s maturity.

Apart from being the title of a regal queen, other Maya concepts of the Evening Star, if there were any, have been lost to the fires of history. Unless they were carved in stone like this portrait of Lady Evening Star on Stela 35 from Yaxchilan. References on Venus, a hugely important theme in Maya astronomy and culture, rarely even mention the Evening Star, though the Maya well knew it was related to the Morning Star as another phase of that planet.

I have no doubt that the famous Dresden Codex probably discusses the Evening Star, but I can’t read through those boggling glyphs looking for mentions and have no idea what it was called in either the Yucatec or Quiché Maya languages. But I really wanted to find out something of the history and mythology of my Vulture trecena patron.

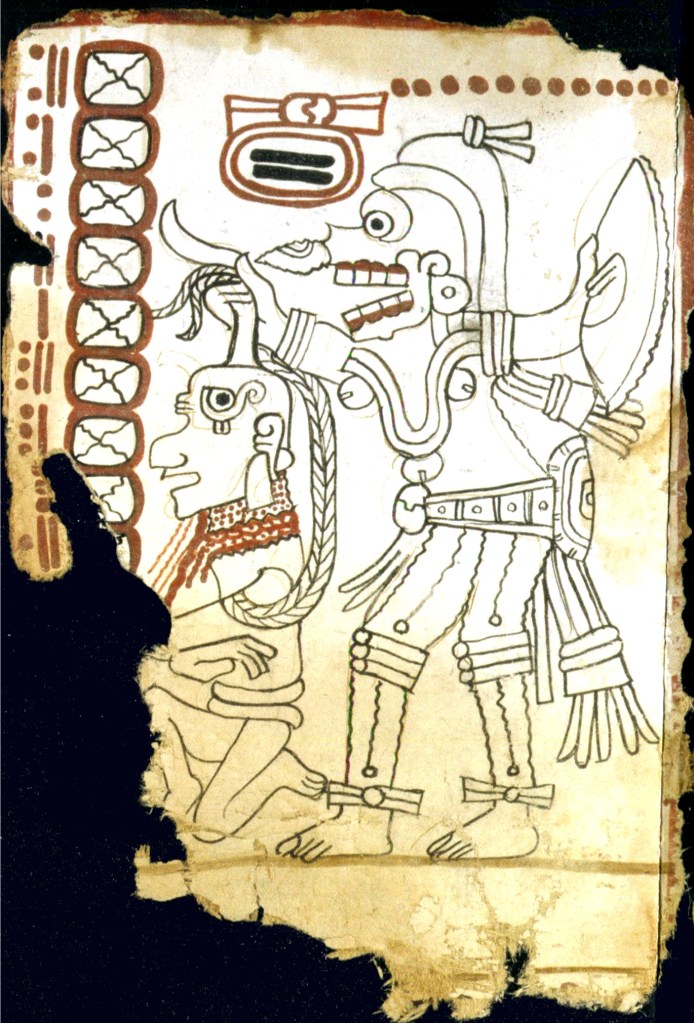

That’s why I went back to my program from the Getty Museum show of the Maya Codex of Mexico (the Grolier Codex), a Maya-Toltec document dating 1021-1154 CE, where in the fragmentary pages on the cycles of Venus, I’d found the Morning Star image that inspired my earlier blog. In fact, for the Evening Star phases, the Maya Codex contains three gruesome images that show a deity with a death’s-head/skull-face. The best preserved presents a deity holding up a victim/prisoner’s bleeding head, apparently having recently decapitated the poor fellow with a large flint knife in his other hand. The skull-faces no doubt mean that the Maya identified the Evening Star is an entity of the Underworld (Xibalba), which wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. They considered life and death a mystical continuum.

The Underworld connection could well belong to an original Maya notion of the Evening Star. In later traditions, it was considered the guide/companion of the sun on its nightly journey through the Underworld. The earlier Maya may well have had a similar myth for the bright star that followed the setting sun. I hesitate to speculate on the Maya meaning of the victim in this scene, but it bears witness to the long-standing tradition of human sacrifice in Mesoamerica. Natural phenomena (like the movement of the sun, the rain, etc.) always came at a price in human blood.

Though the Maya Codex shows the Morning and Evening phases of Venus as different types of figures (including a being with a mask suggestive of a storm-deity), they understood well that it was all the same planet. Maybe Chak Ek’ was actually the deity of Venus itself, making no distinction between its phases: 236 days as Morning Star, 90 days in superior conjunction (behind the Sun), 250 days as Evening Star, and 8 days in inferior conjunction (passing between Earth and Sun). That would explain finding no evidence of separate deities, but of course finding no evidence of something doesn’t prove the absence of that something.

Similarly, I’ve found nothing on what the Venus-phases meant to the culture of Teotihuacan, which certainly revered the planet as the god Quetzalcoatl. That central Mexican metropolis possibly also didn’t separately deify the Morning and Evening Stars. However, the Maya Codex indicates that by Toltec times the concepts of the two phases were diverging, at least in their visualizations. At some time in succeeding centuries, later Nahua cultures evidently completed the separation, generating the new deity Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli (Lord of the House of the Dawn) for the Morning Star and another called Xolotl for the Evening Star.

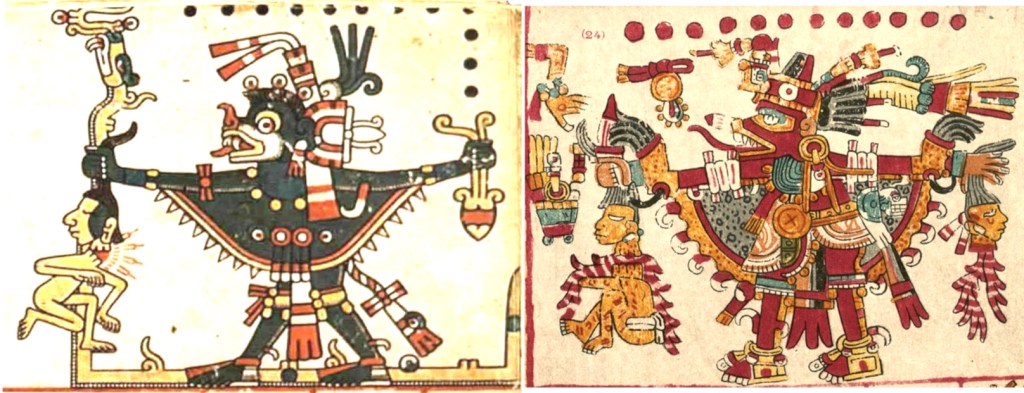

Oddly, they deified the dog as the Evening Star—literally the apotheosis of dog! In two of the surviving “Aztec” codices, the new god appears in strikingly similar poses vividly recalling the decapitation motif in the Maya Codex. The earlier Underworld connection of the Evening Star is suggested by the night-capes both of these Xolotls wear.

Since so little is known about the Maya Evening Star, most authorities like to extrapolate the later mythology of Xolotl back into that period, but I wonder if such lore was in fact inherited. The Maya indeed revered the dog as a guide, companion, protector and bringer of light to darkness, which may have involved escorting the sun through the night. However, Xolotl’s role as psychopomp for souls through the Land of the Dead (Mictlan), eerily paralleling the Hellenic concept of Cerberus in Hades and the Egyptian god Anubis, may well be a later elaboration.

A specific Maya reference to the dog is four images on pp. 25, 26, 27 & 28 of the Dresden Codex shown in relation to rituals for celebrating new years, but I don’t know how that might fit into the ancestry of Xolotl. In any case, they underline the cultural importance of the dog.

Xolotl appears relatively often in the surviving codices, in all but one instance in the guise of a dog. In Codex Borgia the dog-god occurs three times in its typically ornamented style, one too damaged to make out any details. The figure on the left below appears in the “magical journey” sequence, and the central image is from a “heaven temple.” The Sun symbol on its back refers to escorting the Sun through the Underworld at night. Earlier in the codex, as patron of the day Earthquake, Xolotl appears uniquely as a deformed human—which is no doubt why scholars have called him the deity of monstrosities, including twins. (The twin theme obviously refers to the close relationship between the Evening and Morning Stars.)

In two other codices, Xolotl is depicted as a fairly naturalistic dog, unfortunately not naturalistic enough to discern its breed. In the Nahuatl language, “dog” is Itzcuintli, but that’s also a generic term. These images only indicate some sort of a shaggy dog, not at all like the hairless canine Xoloitzcuintli (named for the god) which has been designated the national dog of Mexico. These dogs also look nothing like the small chihuahua which was apparently raised for eating. The spiked collar on the left example I expect is an abstracted “night-sun” symbol, and the explicit anatomy of the central figure is hard to overlook.

Said to have come from the area of Veracruz, Codex Fejervary-Mayer conversely presents Xolotl as a full-fledged, anthropomorphic canine deity ensconced in an elegant temple. In addition, the codex contains several pages with this Xolotl in various aggressive postures, (including eating someone’s head!), which recall panels of Morning Star violence. In one, Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli mysteriously wears a dog’s head. These Codex F-M scenes may indicate a lingering conceptual overlap between the two phases of Venus in a distant conservative area of Mexico.

The scene on the right surely relates to the earlier images with victim, but here blood issues from his body like from a heart sacrifice. Another conservative aspect of Codex F-M iconography is that, except for the first one holding the victim and heart, its Xolotl dog-gods all have the same head—basically that of those anthropomorphic New-Year dogs in the Dresden Codex. Here we see examples of mythological evolution in action.

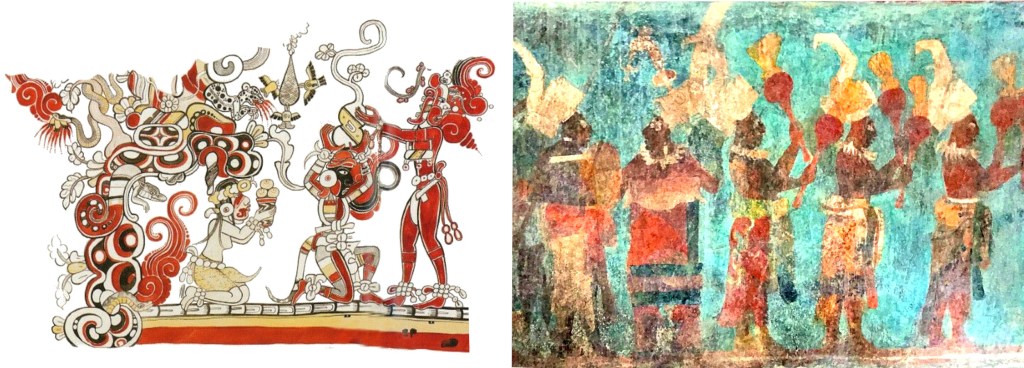

In codices with tonalamatls (books of the Aztec Calendar), Xolotl is celebrated as the patron of the Vulture trecena and formally consecrated as the god-dog, often enthroned.

Besides their masses of divine regalia, all three wear the conch-shell pendant (‘wind-jewel’) symbolizing their connection to Quetzalcoatl/Venus, but none is breed-specific. Curiously, the Vaticanus example is swaddled in a traditional corpse-bundle, perhaps a veiled reference to the Evening Star’s Underworld connection. Now that’s a trio of indisputably alpha dogs!

In its Vulture trecena patron panel, Codex Telleriano-Remensis, an early post-Conquest text painted on European paper, takes the dog to a yet higher level of glory, presenting a fantastic, iconic, metaphorical scene of Xolotl as the brilliant Evening Star with a gleaming Sun (Tonatiuh) setting into the gaping maw of Tlaltecuhtli, Lord of the Earth.

Personally, as an opinionated artist, I think this eye-boggling panel is an absolute epitome of Aztec iconography. You’re welcome to your own opinion. Meanwhile, I’ll note that here Xolotl looks absurdly like a Pekinese, but that makes no difference to the spectacular metaphor.

#

Unlike the myths of the Morning Star, it’s surprising that with the celebrity of Xolotl in Mesoamerica, the Evening Star cult didn’t spread into North America. However, the dog’s traditional loyalty, companionship, guidance and protection was generally appreciated by tribes across the whole continent, and sometimes it was included in rituals and ceremonies. I’ve only found a few legendary references from the Ojibwe and Pawnee (usually about wife or daughter of the Evening Star) and one from the Algonquin about an Osseo, Son of the Evening Star, but there’s no connection to a dog. It seems that Xolotl’s godhead was only valid in Mexico.

But that hasn’t mattered much. All across North America, dogs domesticated humans beings and became de facto gods in their own right, ruling their mortal owners’ Morning (days) and Evening (nights) and living (for the most part) idle lives of divine luxury. Their worshipful care consumes an enormous sector of the economy, I’d bet grossly larger even than that for religious institutions—an apotheosis without even needing an Evening Star mystique or human sacrifice.

###