For at least 35 years, I’ve been fascinated by the art and iconography of the Aztecs of central Mexico, specifically by their ceremonial calendar, and didn’t pay much attention to that of the Maya from several hundred years earlier of Yucatan and Guatemala. I saw little connection between cultures beyond the philosophical structure of the ceremonial calendar that had passed down over millennia from the even earlier Olmec through both the Maya and Teotihuacan to the Toltecs and on to the Nahuatl peoples and late-coming Aztecs. But that was just because I was resolutely ignorant of Mesoamerican history.

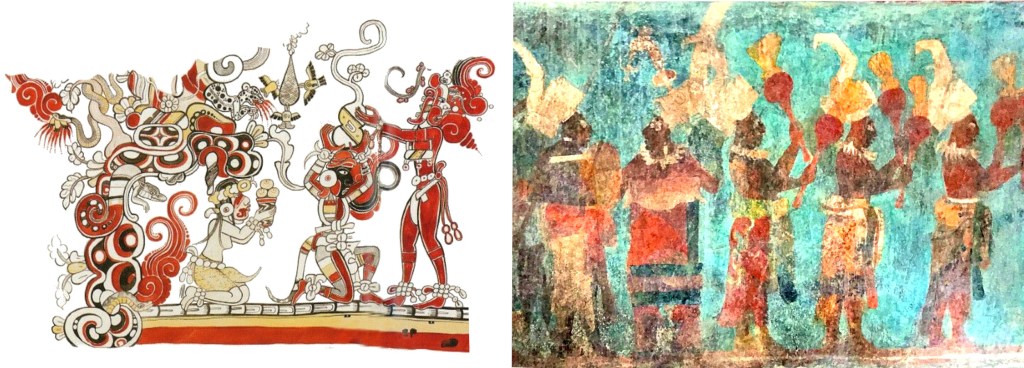

Of course, I’d seen a few examples of the art of the earlier cultures, mostly pieces of Maya murals from San Bartolo and Bonampak:

While remarkably elegant, they didn’t seem to relate much to my favorite Aztec styles and subjects. The same could be said about my passing acquaintance with the few Maya codices that survived the Spanish book burnings like the Madrid and Dresden codices. I never even bothered to look into the Paris codex.

Though impressed with these later Postclassic documents, I left ancient Maya art and mythology to other friends and scholars and blithely continued my intimacies with the Aztec calendar and their wild deities, assuming little iconographic continuity over the intervening centuries.

My ill-informed attitude changed when a kind friend returned from a show at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles in early January 2023 with the program for “Códice Maya de México” (Maya Codex of Mexico). A fourth surviving codex I hadn’t known about, it was only discovered in 1965 and previously called the Grolier Codex. The document has been dated to between 1021 and 1154 CE, earlier the other three Maya codices.

The severely damaged manuscript tracks and predicts the movements of the planet Venus (also the subject of the Dresden Codex), a prime concern of the Maya for both agriculture and divination. Its ten fragmentary panels deal with Inferior and Superior conjunctions, Evening Star, and Morning Star, each with thirteen of the same Maya calendrical day-signs in various disordered numerical sequences. The program explains that each date “marks the crucial first day of a phase of Venus.”

I can’t pretend to understand the astronomical system, but the deities accompanying the phases with their personal regalia and ritual activities were strikingly familiar, also hinting of the art of Teotihuacan and Toltec. Their headdresses, ornaments, pendants, and weapons—as well as bound prisoners— could easily be Aztec images. The panel that particularly held my eye was page 8, the second one dealing with the Morning Star phase:

The repeating day-glyph is Kib—corresponding to the Aztec Cozcacuauhtli (Vulture)—and the sequence 10, 5, 13, 8, 4, etc. (if that’s the direction the count runs), mystifies me. The eagle-clawed deity with bird headdress must surely be the Maya god of the Morning Star known as Chak Ek’. The arrow/spear that he shot into the temple is a familiar motif in the Aztec codices from centuries later.

That and the structure of repeating numbered day-signs recall five mysterious panels in Codex Borgia of Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli (Lord of the House of the Dawn—the Morning Star) attacking gods and places in this way. Checking into those panels, I found them each also accompanied by odd sequences of the same, though different, day-signs. What’s more, similar sets of Morning Star panels in both Codex Vaticanus and Codex Cospi apparently also reflect the Maya theme.

However, while the Maya panels involve the seven day-signs Wind, Lizard, Rabbit, Grass, Jaguar, Vulture, and Flint, the Aztec panels use five different day-signs: Crocodile, Snake, Water, Reed, and Earthquake. So, the Aztecs clearly were using the numbered-day structure of these Morning Star panels for some purpose other than astronomy.

This first set displays an oddly numbered sequence of Crocodile day-signs with the next three day-signs (Wind, House, and Lizard) appearing inside the main panel. The numbering runs clockwise in Borgia from lower right (1, 8, 2, 9, 3, 10, etc.), and counterclockwise in Vaticanus from the same position. This turns out to be the sequence of the day-sign’s occurrence in the calendar count (tonalpohualli), not any notation of Venus cycles.

Meanwhile, in the Cospi version, the lower half of a double panel, the border shows successive days in their properly numbered calendrical order, and with the other half above is a curious sequence of 1 Snake, 6 Death, 7 Deer, and 8 Rabbit. The other Cospi panels for 1 Water, 1Reed, and 1 Earthquake take the odd count through Flower, sorely confusing the basic principle.

All five day-signs, Crocodile, Snake, Water, Reed, and Earthquake symbolize East, which is perfectly fitting for the Morning Star. The border sequences are ordered lists of all calendar days relating to East, and the three other days shown inside the panels represent the other directions:

Now let’s consider the narrative content of the Crocodile (above) and other panels in this series:

Morning Star Panels with Day-Sign Water

In the Borgia series, Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli appears in various guises, a Death god, Eagle, Dog, Rabbit, and another Death god. In Vaticanus, he’s a consistent image of a flayed deity with “dangerous” eyes, and in Cospi he’s more or less the same Death god. In all of these images, he attacks someone or something with a spear. Apparently, bellicosity implies great power.

Considering his victims confuses things. In the Borgia Crocodile set, he attacks Chalchiuhtlicue, in Vaticanus some male god (maybe Xochipilli), and in Cospi Centeotl. In the Snake set, the Borgia victim is Tezcatlipoca, and in Vaticanus and Cospi Chalchiuhtlicue. In the Water set, in Borgia he attacks Centeotl, but in Vaticanus and Cospi the throne of a water deity (Tlaloc?). In all the Reed sets, he attacks the throne of some deity, and in the Earthquake set, he strikes a military symbol in Borgia and the divine jaguar of rulership in the others.

That variation in victims doesn’t explain why the Morning Star is so aggressively pugnacious, but it certainly helps understand how Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli had the chutzpah to attack the Sun God Tonatiuh during the creation of the Fifth Sun. Ever since Maya times, the Morning Star seems to have been a mighty bad boy much to be feared. In Aztec mythology he became an important nagual (manifestation) of the great god Quetzalcoatl, the Plumed Serpent.

On his way to Aztec fame, during the earlier Toltec (Postclassic) era, the cult of the Morning Star was apparently carried in the 12th century by those trader/warriors to the Mississippian civilization in North America. An effigy pipe called “Big Boy” from that period was found at Spiro OK in an astronomical arrangement representing creation myths. It portrays Morningstar, a mythical warrior also known as Redhorn.

The Morning Star was also a Mississippian culture hero referred to as Birdman, and imagery of him with wings and clawed feet like the Maya Chak Ek’ is found in rock art, shell gorgets, and copper ornaments throughout the Mississippian area. In the mythologies of later tribes, he’s a prominent deity/hero: Apisirahts for the Blackfoot and either male or female deities for the Iroquois, Wichita, Pawnee, Ojibwe, Crow, and other tribes. In the Southwest, the Tewa have a Morning Star god called ‘Agojo so’jo (Big Star), a messenger of the Sun associated with warfare. Obviously, for at least a thousand years, the Morning Star has been a mighty myth of the Americas, and it’s still revered among Native American artists.

#