GIVEAWAY #1

REMEMBER NATIVE AMERICA! The Earthworks of Ancient America

By Richard Balthazar

Five Flower Press, 1992

I’m pleased and proud to announce that I’ve now scanned the pages of this long out-of-print book for digital distribution. It’s available now for free download as a pdf file. All you have to do is right click here and select “Save Target (or Link) As.”

Surveying the periods and traditions of earthworking in Eastern North America, the book is an album of more than 120 monumental earthworks in 20 states: conical burial mounds, embanked circles and geometrical figures, animal effigies, platforms, and pyramids.

These earthworks are shown in rare surveys, maps, drawings, and photographs, many reprinted from “Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley” (1841), by E. G. Squier and E. H. Davis, which is itself now available online. Others come from “Report on the Mound Explorations” by Cyrus Thomas (in the 1890-91 Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology) which is also now available online. One of my favorite Squier surveys is the map of Newark works in Ohio:

Some of the photographs of mounds are my own, and those and many others I’ve taken of mound sites since are included on this website in my Gallery of Indian Mounds. Here’s one of the newer ones, a shot of the splendid Pocahontas Mound, a pyramid in Mississippi.

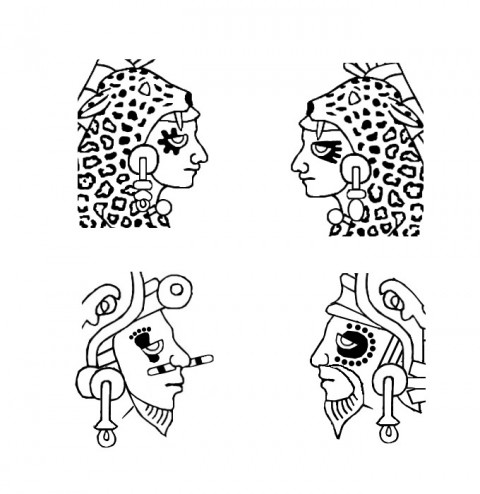

In addition, the book presents a bunch of my line-drawings of artifacts found in mound excavations. They and many more are up for easy individual download in my Gallery of Pre-Columbian Artifacts. One of my favorites, albeit disturbing, is a curiously Toltec-looking warrior about to behead a captive.

For free download of REMEMBER NATIVE AMERICA! as a pdf file, just right click here and select “Save Target (or Link) As.”

Now I’m going to steal this opportune moment and bore you with my rant about earthworking, which I believe is a truly primordial human instinct. Man, the animal who makes things, had to start somewhere. Originally, of course, things could only be made out of animal material, plant material, stone, or earth, and most of that only after first making the tools or utensils necessary for the manufacture. Since anything that worked, even plain old stones and sticks, would suffice for the job of moving dirt around, I suspect that the first implements (besides clubs for bonking folks and things) were probably whatever could be used to dig up food roots or enlarge shelters.

It’s but one short step from moving dirt around to piling it up. As far as we know, people started constructing earthworks several thousand years ago in most parts of the world. Everywhere you look, they raised piles of dirt in one form or another, often as tomb monuments. The ziggurats of Sumer were simply piles of mud bricks. Did the ancient Egyptians build in stone because you can’t effectively pile up sand? Just wondering.

The impetus to heap up piles of dirt may well have come from observing nature. Anthills and all that. Also, it stand to reason that if you’re digging a hole for some reason, you’ve got to put the dirt somewhere. What’s more, the primordial mind probably saw hills and mountains as the handiwork of some deity or other, and so raising earthen mounds likely had religious purpose, sympathetic magic and such. Piling the dirt in special shapes would only add to the symbolism, and it seems that the very location and orientation of the piles often was astronomically or socially significant.

I’ll end this rant by noting that ceramic technology is also in fact earthworking, another part of Man’s artistic relationship with the Earth.