At long last –Aztec Icon #11: OCELOTL, Lord of the Animals. In the midst of other projects and family stuff, it’s taken me all summer to finish this icon for the coloring book YE GODS! THE AZTEC ICONS. Not for lack of effort but the enormous amount thereof. Actually I’d already done the jaguar rampant a couple years ago, my first drawing directly to digital. Thanks to my freeware graphics program GIMP, in rendering this boggling Mesoamerican zoo, I’ve discovered almost godlike powers over pixels. But I try to be a beneficent deity.

The vast amount of effort came first in locating historical images of creatures in the ancient codices for stylistic models. Those I couldn’t find had to be drawn from photographed nature. Actually, my iconic jaguar is a departure from Aztec style in its naturalistic treatment. While there are many jaguars in the codices, in my opinion they all look too “cartoonish” to make an impressive deity. Besides, I liked the challenge of creating the pelt pattern for the little Jaguar Knights in the Chalchiuhtotolin icon. The regalia indicates the creature’s divine nature, and the wavy fork at its muzzle is the symbol of its howl.

Please note the large “dots” at each corner of the icon. They are the Aztec number four, and this is the calendrical day-name Four Jaguar, the First Sun (World) in the Mesoamerican cosmological sequence. That very first YE GODS! icon of Atl was the day-name Four Water, the Fourth Sun, and the fifth icon of Ehecatl was the day-name Four Wind, the Second Sun. You’ll have to wait a bit for the third and fifth Suns later in this series.

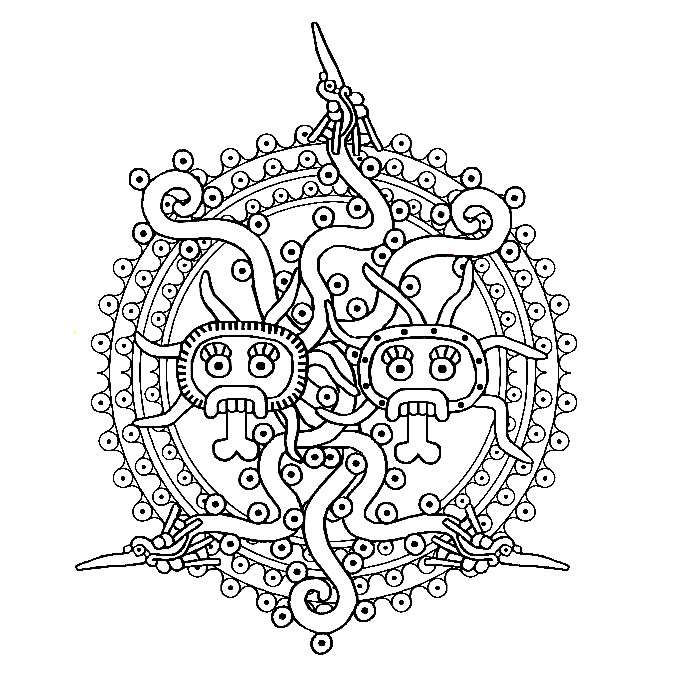

Ocelotl is lord of all animals: those belonging to Huixtocihuatl, Lady of Salt (Goddess of the Sea on the upper left); those belonging to Tlaltecuhtli, the hermaphroditic Lord of the Earth (on upper right); and those of the air ruled by Quetzalcoatl, the Plumed Serpent (at top).

The split circle over the deity’s head is the traditional symbol of day and night, showing its lordship over diurnal and nocturnal animals, the jaguar itself being nocturnal. The eagle to the left represents the Aztecs’ main god Huitzilopochtli as the sun at midday, and my very own “batterfly” on the right is Itzpapalotl, Goddess of the Night Sky, who was often depicted as butterfly, bat, and/or bird.

Ocelotl is also lord of the strange animal Man, as can be seen in the vignette at the bottom depicting the legendary creation of man from a primordial tree as shown in Mixtec codices.

By the way, I’ll note that the Aztecs adopted most of their cosmology and “religion” from the peoples living then and earlier in central Mexico like the Mixtec, Zapotec, Huastec, Toltec, etc., etc.—as had they from the even more ancient Teotihuacan and Maya. In the long history of Mesoamerican civilizations, their underlying myths have mostly been related, even inherited.

Ocelotl, the Jaguar, is a mythology from deep in history. The earliest (in Mesoamerica) Olmec famously revered the Jaguar (jaguar-headed babies?), and may have named the day in the calendar for it. Or maybe not. Elsewhere I’ve suggested that the Mesoamerican calendar could have come from South America, from the even earlier Chavín civilization, and curiously, the Jaguar-Man was also a prominent feature of that culture. Just saying… Deep history.

Some other notes on my Mexican menagerie: I can’t even identify some of the animals or birds, especially the silly little bugs. That odd creature at the end of the deity’s tail is the salamander called in Nahuatl axolotl. My Monarch butterfly (center left, just above the stunning Turkey) is geographically appropriate, as are my several other nature drawings of Mexican fauna, including the quetzal birds (top right). Don’t overlook the Xoloitzcuintli, national dog of Mexico, at the Jaguar’s left foot. Can you identify any more of the critters in this montage?

(You can still see or download the previous ten icons in the YE GODS! series by clicking on them in the list on the page for the coloring book.)

ICON #11: OCELOTL

(Lord of the Animals)

To download this icon as a pdf file with a page of caption and model images from the Aztec Codices, right click here and select “Save Target (or Link) As.” You can also download it in freely sizable vector drawings from the coloring book page.

OCELOTL (Jaguar), Lord of the Animals

OCELOTL {o-se-lotł} (Jaguar) is the Aztecs’ deity of all animals of land, sea, and air. It is a nagual of the god TEZCATLIPOCA who created the First Sun, Nahui Ocelotl (Four Jaguar), a world peopled by giants who were devoured by divine jaguars. Ocelotl, the 14th day of the month, was usually a lucky day, but anyone born on the day Ce Ocelotl (One Jaguar) was destined for sacrifice to one god or another. OCELOTL is patron of scouts and warriors, and the elite corps of warriors of the night were known as the Jaguar Knights. Ever since the Maya, in Mesoamerica jaguar pelts in shades of tawny gold to white were the sacred possessions of priests and royalty.